Thinking Things Over February 26, 2012

Volume II, Number 8: The Stock Market, Dependent upon Economic Policy Prospects, Will Predict November’s Election Winner

By John L. Chapman, Ph.D. Washington, D.C.

I refuse to leave our children with a debt they cannot repay. We cannot and will not sustain deficits like these without end. … We cannot simply spend as we please. — Barack Obama, February 23, 2009

Americans are tired of being tired. It’s clear that the American people have decided it’s time to get up. They’re tired of being told that we’re in a long, slow drift. — Joe Biden, February 24, 2012

If you don’t try to generate more revenues through tax reform, if you don’t ask, you know, the most fortunate Americans to bear a slightly larger burden of the privilege of being an American, then you have to — the only way to achieve fiscal sustainability is through unacceptably deep cuts in benefits…. — Timothy Geithner, February 24, 2012

The Past as Prologue

The study of human history evinces one primordial lesson: events — and human destiny — can turn on single individuals or circumstances that fate and timing have conspired to issue forth. Had the Spanish Armada defeated the English fleet at Gravelines and in Channel battles in 1588, for example, pressing the advantage to depose Elizabeth I, the world would speak Spanish today. Similarly the exemplary life of George Washington, celebrated this past week in remembering his birth 280 years ago, can be shown to be a case of the exact right man for the time and the events; had there been no General Washington, American (and world) history would be very different today. Or, suppose the United States had stayed neutral in the world war begun in 1914, and not become an active belligerent in 1917. It is more than likely the Germans, French, and British would have fought to a truce, perhaps involving German territorial gains west of Alsace-Lorraine, or overseas concessions. But the German Reich of Kaiser Wilhelm would have survived intact, never been crippled by Versailles, and the seething hatreds of Hitler would have never been unloosed upon the world.

One is reminded of this in contemplating this election year of 2012, and what it will mean for the trajectory of U.S. and world history in its wake, as well as for our more parochial purposes in seeking to discern wealth-preserving and growth investment opportunities around the globe. This issue was broached again in the past week with competing tax reform and fiscal spending strategies enunciated by President Obama and a potential Republican rival this fall, Governor Mitt Romney. For whatever the differences between the competing economic growth plans of the Republicans, any of them will represent a major break from Mr. Obama’s designs, and imply different paths for the economy in the future.

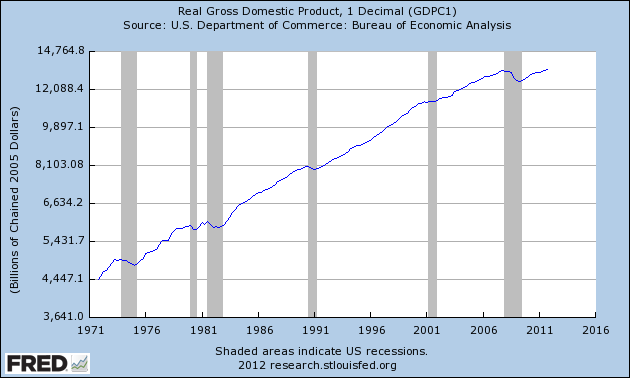

It is helpful to think about this — that is, about history’s particular effects being rooted in terms of individuals and/or seminal events — when looking at the growth of real output in the U.S., per the graph below covering the last 40 years in the United States. This is because, as can be demonstrated, the changes in the slope of the graph can be interpreted in light of the generally-coincident change in the macroeconomic policy mix:

Chart I. Real GDP Growth in U.S., August 15, 1971 to 4th Quarter 2011 (Log Scale)

The chart, which is logarithmic to display equiproportional changes, begins on August 15, 1971 — the dawn of global fiat money and end to monetary gold. While the 40 years period shows one of general progress, the different trajectories in growth, which can only be discerned by reading the graph slowly across time (left to right), conform roughly to differing policy eras. Nixon-era wage and price controls matched with spending growth allowed for strong profits and output growth in 1972-73 (GDP growth was near 5% across these two years), but with the end of controls came an inevitable punishing inflation in 1974. The ensuing nine-year period (1974-82 inclusive) ranks very near the worst in U.S. history over an extended time-frame: fitful growth led to 2.0% per year across the nine years, with 9.1% average annual inflation, and unemployment that peaked at 10.8% in the fourth quarter of 1982. It is important to recall as well that U.S. equity markets had been completely flat in nominal terms across these nine years, and if not beginning a sharp rally in mid-August of 1982, would have been down for the entire period (in inflation-adjusted terms U.S. equities lost 44% of their value between 1974 and the end of 1982). It was, alas, a terrible time for capital investment and technological advances in U.S. industry, a surefire condition for elevated unemployment.

But on January 1, 1983, two years into President Reagan’s very public backing of the Volcker Fed to promote a stronger dollar regardless of the political consequences, his roll-out of a 25% reduction in marginal tax rates commenced. Additionally, Mr. Reagan led an aggressive promotion of regional and bilateral free trade agreements, pressed for deregulatory commitments across the government (including lessened antitrust emphasis and a laissez-faire approach to the telecommunications sector, itself long ripe for revolutionary advances if and when the federal government’s watchdog organs were held at bay), and focused the entire federal apparatus on fiscal spending restraint.

The Wall Street Journal’s Robert Bartley called the rest of the decade the “seven fat years“, as GDP growth averaged well over 4% per year, and inflation and unemployment were both more than cut in half (the latter down to 5.2%). The stock market was up 165% and more than 20 million jobs were created in these seven years. After two down years in 1990-91 that included major tax increases and a short war with accompanying Middle East instability, the ensuing nine years (1992-2000 inclusive) were again ones of high prosperity, with five of those nine years at more than 4% GDP growth. Another 20 million jobs were created as unemployment fell below 4% late in the decade, and inflation averaged 2.8% in the 90s. The stock market likewise more than tripled in the 1990s (up nearly 15% per annum in real terms), and the U.S. bond market, which bottomed out on Election Day 1994, rallied strongly across the next six years as well in an investment-led productivity boom.

As the flattened graph shows after the year 2000, things have been more troubled for the U.S. economy in the combined Bush 43/Obama years. Economic growth across these 11 years has averaged only 1.6% per year, and there have been no new jobs created on net — this is the first time in American history this has ever happened, and this is unquestionably the worst 11 year period for growth in jobs and output in American history other than the 1930s. U.S. equities have, correspondingly, performed very poorly in the last 11 years and are essentially flat across that time-frame.

What the macroeconomic data on output, employment, investment, and prices show over time is that policy matters. Good economic policies, by which we mean those conducive to growth and prosperity, are a function of the political regime — regardless of which party is nominally the head of government — and its degree of commitment to those policies. Presidents Nixon, Ford, and both Bushes, for example, were Republicans, and supposedly therefore attached to the Republican Party’s nominal branding as a pro-economic growth, pro-limited government party. But Mr. Nixon gave us the EPA, OSHA, an end to gold, and wage-price controls, stating that he was “a Keynesian in economics.” Mr. Ford continued the Nixon policies and trashing of the U.S. Dollar’s value, while Bush 41 signed huge tax increases into law alongside spending growth. Bush 43 was, before Mr. Obama, the biggest domestic spender since LBJ, signed into law the largest expansion of the entitlement state since Medicare’s original passage, supported bank and auto bailouts, and governed while federal spending went up from 18.2 to 21% of GDP during his term.

Mr. Clinton, meanwhile, a Democrat committed to universal healthcare, presided over a a flat-lining of discretionary spending, signed major welfare reform into law, signed NAFTA, backed strong dollar Treasury Secretaries, and governed while federal spending and debt to GDP ratios both declined significantly (his four final years in office entailed cash budget surpluses, for the first time since the 1970 fiscal year). In contrast to Nixon-as-Keynes, Mr. Clinton stated in his 1995 State of the Union address that “the era of big government is over.” Even if a Republican Congress forced good behavior upon him in terms of fiscal restraint, Mr. Clinton ended up preserving key aspects of the Reagan policy mix (other than, importantly, the Reagan tax rates after 1986), and the 1983-2000 period was the best overall in the Federal Reserve era, and perhaps the best in U.S. history, all things considered.

What This Means for 2012

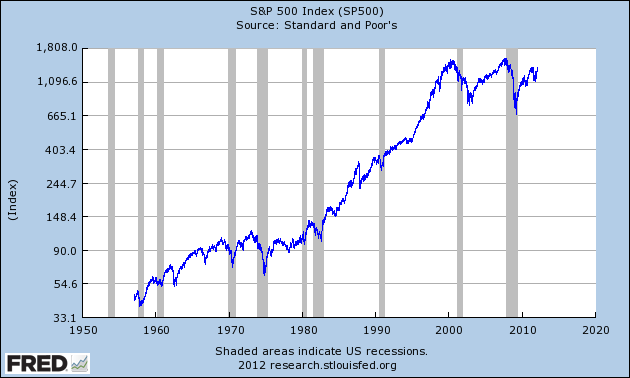

With this as background, what are the prospects for U.S. financial markets and the economy moving forward? Here is the S&P 500 Equity Index going back to 1957:

Chart II. S&P 500 Index, 1957-Present (Log Scale)

We show this graph dating to 1957 in order to show the run-up in U.S. equities prior to the post-1971 policy era discussed above, and also to highlight the “choppiness” of returns prior to the advent of the Volcker Fed after 1979. That is to say, in keeping with the policy activism in place during the heyday of “Keynesian fine-tuning”, where interest rate and money supply-changing moves were made frequently in hopes of providing perfect counter-cyclicality to a world that was assumed to be governed by the Phillips Curve (inflation-or-unemployment) trade-off, the Federal Reserve sought to both complement fiscal policy and respond to changing economic conditions in an immediate way. But the result was excessive “stop-go” monetary policy which led to volatility in market returns.

We show this graph dating to 1957 in order to show the run-up in U.S. equities prior to the post-1971 policy era discussed above, and also to highlight the “choppiness” of returns prior to the advent of the Volcker Fed after 1979. That is to say, in keeping with the policy activism in place during the heyday of “Keynesian fine-tuning”, where interest rate and money supply-changing moves were made frequently in hopes of providing perfect counter-cyclicality to a world that was assumed to be governed by the Phillips Curve (inflation-or-unemployment) trade-off, the Federal Reserve sought to both complement fiscal policy and respond to changing economic conditions in an immediate way. But the result was excessive “stop-go” monetary policy which led to volatility in market returns.

Nonetheless, what is clear from a comparison of the two charts above is their general congruence, in terms of how the first begets the second. In other words, the lousy Nixon-Ford-Carter economy of the 70s and early ’80s, particularly the “lost nine years” of 1974-82 (inclusive), produced a lousy stock market. Similarly the Bush 43/Obama era, in which spending has exploded, the U.S. Dollar’s value has declined sharply, and new costly mandates and regulations have added to the government’s unfunded liability streams, have also portended a poorly-performing stock market.

On the other hand the 1983-2000 period, covering Reagan and Clinton’s tenures and their commitment to a strong dollar and a generally laissez-faire policy mix, was a bright one for U.S. equities and global economic growth led by the strong U.S. economy. While the old adage that “the stock market is not the economy” is certainly always to be kept in mind, and indeed, while the causation or correlative timing is hardly sacrosanct, looking back on the broad sweep of history clearly shows that the policies that generate prosperity — viz., low tax rates on capital, profits, and income, a strong dollar, free trade, and sane fiscal and regulatory frameworks — do indeed lead axiomatically to a rising equity market. Conversely, as those policies which grow the size of government by shrinking the private sector come to dominate the scene in political economy, they also at the same time lead to sclerosis in equity markets. Again, the correlation is hardly perfect — the massive drop in U.S. equity markets in 2008 hardly could have been pinned to any great degree on Mr. Obama’s election — but in times not stricken with financial panic, the stock market can be a reliable indicator of voter preferences.

What does this portend for 2012? While every situation is unique, past history does offer us a few clues. 1980, for example, was a year of high unemployment, high inflation, deficit spending, 21% interest rates, and big trouble abroad (e.g., hostages in Iran, Soviets in Afghanistan). The contrasting economic philosophies between the two major party candidates were stark in their differences. The S&P 500 Index, after being completely flat for three straight years between 1977 and 1979, exploded in 1980. In fact, between Ronald Reagan’s announcement of his candidacy for President on November 13, 1979 and his election on November 4, 1980, the S&P was up by more than 28%. There were plenty of reasons why the market should have been down in 1980, and there was only one reason for it to gain: the prospect of a capital investment-friendly, pro-entrepreneurship, and pro-private sector White House in 1981.

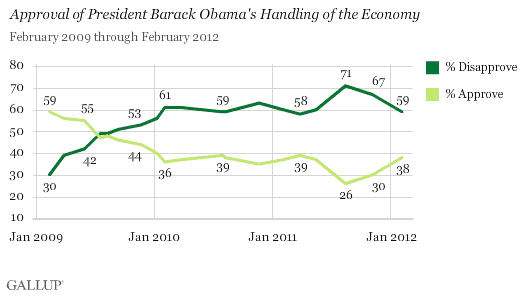

It is clear to this observer that Mr. Obama has forfeited the early confidence people had in his ability to induce a sustainable recovery in the economy, post-2008 meltdown. He pursued highly unpopular and extremely costly legislation for health care that has resulted in a Supreme Court-adjudicated lawsuit that was joined by 26 states against the federal government, and to this day, two years on, a majority of voters disapprove. He promised to cut the deficit in half, to no more than $533 billion, by the end of his first term; all his deficits will end up being in the $1.2-1.5 trillion range. Mr. Biden and his staff promised an unemployment rate that would not exceed 8% post-stimulus, yet we have suffered for three years with rates far higher than this. The Vice President promised a “summer of recovery” in 2010 and up to 500,000 jobs being created every month, but the reality has been anemic job growth in comparison to all past recoveries. And the President’s new tax proposals, while maddeningly vague per his usual refusal to detail specific plans, still call for a framework of steeper progressivity in the tax code, and a new marginal rate of at least 41% on up to thirty million small business owners in the U.S. For high-income earners the new marginal rates on capital gains and dividends, including the prior taxation as ordinary income, could go as high as 58%, before state and local taxes are applied (and deductions for which might be lost in a “closing of loopholes”). All of this has led to Mr. Obama’s dismal approval ratings on the economy three years into his term:

Chart III. Current Obama Approval Rating for Handling of the Economy (from the Gallup Organization)

While the current approval rating of 38% is up sharply from the 26% registered six months ago, and while high frequency data for the U.S. economy continues to point toward growth this year in the 2.5-3% range, the above-rating is a dagger in the heart of the Obama 2012 campaign. In this regard, Governor Romney, an extremely weak candidate by any measure, helped his chances this past week with a revamp of his economic plan: Mr. Romney’s plan, designed by Glenn Hubbard of Columbia Business School and Harvard’s Greg Mankiw, now calls for a 20% cut in all federal tax rates, permanently. Mr. Romney also promises repeal of ObamaCare and Dodd-Frank, and a rollback of federal spending in a “significant” way; this is far and away the best week of his campaign.

While Governor Romney is no Reagan, the contrast he or any of the other prospective Republican nominees represents vis-a-vis Mr. Obama might come to be seen as stark as it was in 1980. There are, again similar to 1980, storm clouds on the horizon that make this a difficult year to predict (viz., we do not think Greece or the Eurozone challenges have been settled; Israel and Iran may get into an armed conflict; China is imbalanced and prone to a bubble collapse, and so on), but the issue has been settled for investors and many workers, too. That is to say, like the capitalists in Ayn Rand’s novels, they have gone “on strike” against the Obama economy, in terms of cash on the sidelines, lack of investment plans, and for the workers, lack of hiring (relative to robust recoveries in the past) and lack of labor force participation.

It therefore seems to us that the greater the chance that Mr. Obama is retired this fall, the better U.S. equities will do, in anticipation of better (pro-growth) policies in the future. The 8.4% gain in the S&P 500 so far this year is impressive, but cannot possibly arise from investor confidence in the Eurozone’s ability to handle the rolling tragedy there, or in Israeli quiescence in the face of extermination threats (for the record, we actually believe the Iranian leadership is more rational than it lets on, and do not think they will attack Israel, even post-nuclear capability; but we understand Israeli concerns to the contrary, and the chatter inside the Beltway about the potential for war there this year is at an all-time high now), or in declining oil prices, a Fed-led strong dollar, continual 10% Chinese growth, or least of all, in a return to U.S. fiscal sanity and sustainable growth.

Rather, what is buoying equities in our view are four factors, three that seem apparent, and the one we have been discussing per the foregoing: (a) the oversold nature of the bond market; (b) investor fear of international asset classes, given the turmoil in places such as Europe; (c) better and now more-readily acknowledged U.S. fundamentals; and to an extent that may grow over time, (d) the so-far subterranean thinking that “policy regime change” is in the offing in the year ahead in U.S. politics (and by the same token, if markets falter badly this year absent a Eurozone blow-up or Mideast war, in our view a driver may well be that Mr. Obama looks like a likely winner in that case).

Astute investors will continue to monitor all these countervailing influences on asset prices over time, but for us, the last one may become dominant in the months ahead — particularly if one of the Republicans can develop a coherent counter-vision to the future Mr. Obama has outlined. For Mr. Obama — indeed, for the country — it has been three lost years and a squandered historic opportunity, to lead the world away from a once-a-century panic, and toward a sustainable future of economic growth and prosperity borne of fiscal prudence. But the sad reality now is, if Messrs. Obama and Biden somehow were removed from the scene in favor of the opposition party, we would see a solid and sustained rally in U.S. markets. Conversely, had President Reagan and Vice President Bush been removed at the equivalent juncture three years into their first term, in early 1984, in favor of the opposite party, markets would have swooned badly. It is to their discredit that the Obama team do not apprehend this — and never will.

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, John Chapman can be reached at john.chapman@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com. The views expressed here are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect that of colleagues at Alhambra Partners or any of its affiliates.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

Stay In Touch