Thinking Things Over April 8, 2012

Volume II, Number 14: Liquidity Traps, Unemployment, and the Future of U.S. Equity Markets

By John L. Chapman, Ph.D. Canton, Ohio.

Friday’s less-than-robust unemployment report has its origins in monetary mismanagement, with attendant consequences for investors. In the following essay we connect the dots.

In the spring of 2003 then-Fed Governor Ben Bernanke travelled to Tokyo as the guest of the Bank of Japan’s Tokiko Shimizu, who arranged meetings for him with the then newly-independent BoJ, as well as the Ministry of Finance and Financial Services Agency (Japan’s analogs to the U.S. Treasury and SEC, respectively). During his visit to Japan, which was then in its thirteenth year of a long torpor entailing sclerotic economic growth and stagnant incomes — a period of time that has now stretched to more than two decades, including the most recent four quarters of post-earthquake output contraction — Mr. Bernanke also gave a speech to the Japan Society of Monetary Economics. In words that he could not have then presciently known would soon apply to the United States as well, Mr. Bernanke took pains to affirm the newly-won independence of the Bank of Japan and its discretion in grappling with a long running period of deflation (and depressed output):

[T]he role of an independent central bank is different in inflationary and deflationary environments. In the face of inflation, which is often associated with excessive [government borrowing and] monetization of government debt, the virtue of an independent central bank is its ability to say “no” to the government. [In a liquidity trap], however, excessive [government borrowing] and money creation is unlikely to be the problem, and a more cooperative stance on the part of the central bank may be called for. Under the current circumstances [of a liquidity trap and deflationary recession-like conditions], greater cooperation for a time between the [monetary] and the fiscal authorities is in no way inconsistent with the independence of […] central bank[s], any more than cooperation between two independent nations in pursuit of a common objective [or, for that matter, cooperation between central banks and fiscal authorities to facilitate war finance] is inconsistent with the principle of national sovereignty.

For Mr. Bernanke, whose academic career was made on scholarly work analyzing the Great Depression, falling price levels are emblematic of declining aggregate demand and hence are, ipso facto, injurious to the macro-economy; deflation is a great “enemy” that can only be defeated via “reflation”. For Japan, real GDP that has averaged less than 2% growth per annum since 1990 has led to declining living standards relative to the rest of the world, and according to the Fed Chairman a prime cause for this is the deflationary spiral of both asset and consumer prices. Mr. Bernanke clearly believed that Japan then was (and still is) in a Keynesian-like liquidity trap — and policy allies ranging from Paul Krugman to Nouriel Roubini agree with his implicit assessment that the same is currently true of the United States. Analyzing Fed policy direction when mapped against current economic conditions as proxied by the unemployment data can give us clues as to near term prospects for U.S. equities and economic growth.

What is a “Liquidity Trap?”

We would certainly agree with Chairman Bernanke that Japan’s problems are “complex,” and there is sadness at the human toll involved in the stagnation there: Japan, once in the top five of the wealthiest nations in real per capita terms, has now slipped to 38th; once eighty percent of American living standards, Japan is today closer to 70% of U.S. per capita income. But we part company with Messrs. Bernanke and Krugman in terms of both causes and remedies of macro-economic stagnation, starting with their belief in the viability of the concept of a “liquidity trap”, and including as well Mr. Bernanke’s insouciance over monetary easing per the above quote. First, in his 1936 magnum opus (The General Theory), Keynes asserted that an economy in recession would suffer investors’ “fetish” for liquidity; that is to say, the demand for money would increase dramatically in times of uncertainty and depressed aggregate demand. With elevated preference for liquidity (over money’s main substitute, interest-bearing bonds, according to Keynes), itself a primal cause of deflationary forces on the price level, interest rates would fall, ultimately to approach the zero-bound. In such a case, monetary policy was wholly ineffective in jump-starting the economy because investors were both fearful and because they anticipated bond prices falling, and wanted to have liquidity to exploit a profitable buying opportunity. According to Krugman, the U.S. has only been in two liquidity traps ever, the 1930s and today.

The remedy in such an instance was, for Keynes, quite clear: deficit-spending by the government would jump-start production and increase aggregate demand (providing a “jolt” to the economy, as Obama economic advisor Austan Goolsbee liked to say in 2009), leading to growth in jobs and incomes. Mr. Bernanke would agree with this line of thinking; only now, as Fed Chairman, he of course would never concede that monetary policy was ineffective if not wholly powerless. Instead, his promise for yet another round of quantitative easing, if need be, is precisely geared to support such fiscal spending activism. Again, this line of thinking does not countenance price level deflation, and its abnegation would be the primary focus of the QE3 we still anticipate, perhaps later this year.

In his seminal 1963 book America’s Great Depression, the late Murray Rothbard forcefully reproves Keynes by citing the crux of his error in logic:

Keynesians claim that “liquidity preference” (demand for money) may be so persistently high that the rate of interest could not fall low enough to stimulate investment sufficiently to raise the economy out of the depression. This statement assumes that the rate of interest is determined by “liquidity preference” instead of by time preference; and it also assumes again that the link between savings and investment is very tenuous indeed, only tentatively exerting itself through the rate of interest. But, on the contrary, it is not a question of saving and investment each being acted upon by the rate of interest; in fact, saving, investment, and the rate of interest are each and all simultaneously determined by individual time preferences on the market. Liquidity preference has nothing to do with this matter.

In other words, interest rates in a free market are determined in the market for loanable funds, as settled between lender/creditors and borrower/investors who are trading assets and command over scarce resources between present and future. A high time preference for resources to be used or consumed in the present will result in higher interest rates, as this higher demand for current resource availability will pull goods and resources away from future-oriented investment uses and into current consumption. Conversely a low time preference, where demand for future goods supersedes any orientation for the present, will lead to lower interest rates, less consumption, and more investment.

The demand for money, meanwhile, has its roots in needed liquidity for, as Keynes himself had once said, transactions, reserve/precautionary, and/or speculative motives. Further, deflation is not the same thing as, or resultant from, an increase in the demand for money, strictly speaking, nor is it tantamount to falling prices. Deflation is a decline in the quantity of money and credit in circulation, due most often to deleveraging, which itself is driven by declining demand. Falling prices often result from this circumstance, but as A.C. Pigou pointed out in critiquing Keynes, this falling price level is the antidote to the deflation and any harm that arises from it. Because in fact, deflation unambiguously increases the real value of cash balances, thereby increasing the real wealth and purchasing power of holders of money.

Given this, there is in reality no such thing as a “liquidity trap” — at least in a pure free market, that is, one free of monetary manipulation by the government or its central bank. Messrs. Bernanke and Krugman evidently have never stopped to ask themselves, what is the source of the heightened demand for money causing the “liquidity trap?” It is not due to any anticipation of falling bond prices, as Keynes averred; rather, it is due to macroeconomic disquiet — or what economist Robert Higgs has formally termed “regime uncertainty.” Colloquially, we can call it simply investor and consumer fear: the antidote to policy-induced fear is of course recast policy, which eliminates the basis for or the drivers of the investor uncertainty.

This in turn explains the error borne of Mr. Bernanke’s thinking as evinced in the quote above. The Fed Chairman readily admits deficit-spending and increasing debt levels that come with inflation are bad; but, he claims, excessive government borrowing and rising debt levels along with any attendant money creation are not problematic: like Keynes, Mr. Bernanke ignores the teachings of J.B. Say, and thinks that spending begets demand and the creation of real wealth. Instead, government intervention into a market economy such as we have seen in recent years, when massive jumps in government spending occur in tandem with equally-massive monetary and interest rate manipulation, have two very negative and long-lasting effects: levels of fear and uncertainty are heightened, causing a decline or at least a stultification of job-creating investment, and secondly, the scarce capital of the society is often wasted in large amounts on boondoggle spending or wholly-corrupt political and cronyist ways. This, of course, guarantees a lower rate of economic growth and less prosperity in the future. And in an immediate sense, the increases in government debt and deficit-spending which the easy money policy ratifies not only waste scarce capital in a “current” way, but also retard the liquidation of previously-erroneous investment (or, “malinvestment”).

(We cannot fail to mention that the Bernanke/Krugman animosity toward deflation as a general matter is further misplaced, when thinking of deflation in terms of what is in fact its consequence, falling prices. Indeed, prices may and often do fall for reasons of increasing productivity, in which case the decline in prices results in increases in real incomes and real wealth for holders of purchasing power. The 1873-96 period in the United States is a prime example of a deflation that occurred for a long period alongside very real economic growth and progress, with amazing advances in energy [e.g., electricity, petroleum, diesel engine], transportation [railroads, faster seaborne travel], agriculture, and industry.)

In sum, the war conducted by some in the economics profession on an entirely false precept known as the “liquidity trap” is entirely misplaced, and elicits one sure macroeconomic result: a weaker currency, capital decumulation, and heightened investor fear.

Disconcerting Employment Data for March 2012

This errant monetary policy in turn begets — and underlies — a generally lackluster economy, and directly explains the lack of robust job growth. For what is increasing employment of labor, if not an investment in the productive capacity of tomorrow, and a bet on the future? Keynes was surely right to observe that a decline in investor animal spirits would in turn lead directly to a lower level of economic activity and a poorer society in the future. We saw this anew this past Friday, when the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics released employment data for March 2012, showing 120,000 new payroll jobs were added to the labor force last month. U.S. unemployment now stands at 8.2% of the total workforce, down from this recession’s peak of 10% in 2009, thanks to both four million new private sector jobs in the past two years, as well as a labor force participation rate that has declined from 65.5% three years ago to 63.6% today.

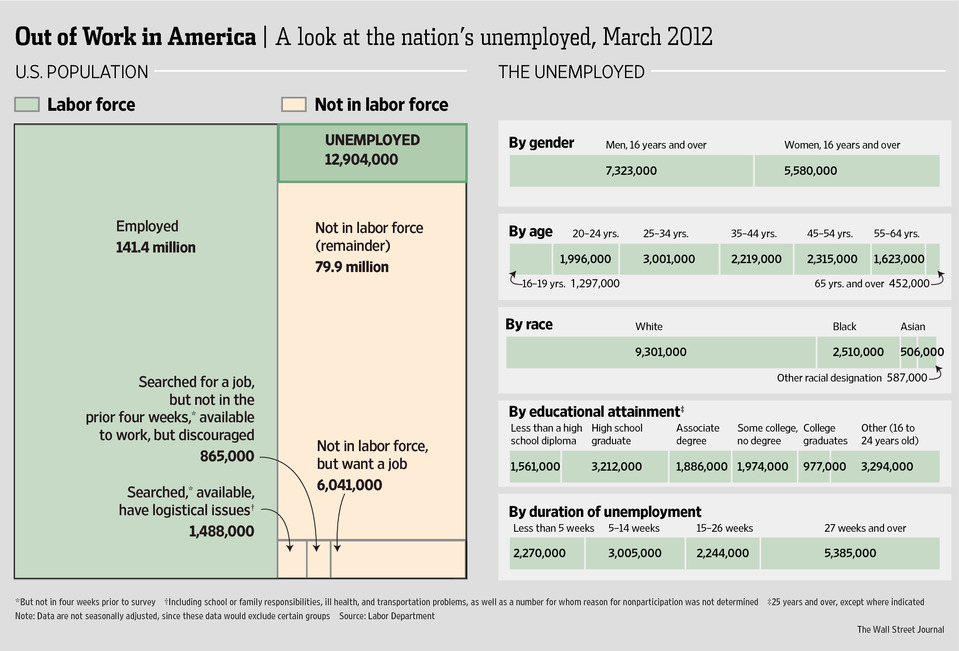

But investors understood this was not good news, after three months of well over 200,000 new jobs each, and per capita work-hours declined as well. Further, real incomes have increased roughly 2% over the last year, below the all-in inflation number of 2.9% over the last 12 months. The Wall Street Journal published an arresting graphic highlighting the challenges of the current environment for employment:

Chart I. Unemployment and Underemployment in March 2012 (Courtesy of Wall Street Journal, 4/7/12)

A few points about this breakdown are alarming: first, in addition to the nearly 13 million unemployed, there are another 8.4 million people not counted in the official statistics who are discouraged, who have not looked for work in the last month, or have logistical problems of various types preventing them from working. Further, the number of “chronic” long-term unemployed (officially defined as 27+ weeks) as a percentage of the total remains historically elevated above 40% of all unemployed; this is a very bad sign for their future productivity and prospects for recapturing prior living standards. And lastly, the Labor Department’s claim of a decline in the workforce participation rate by nearly two full percentage points just since Mr. Obama took office, based on estimates of Baby Boom retirements, does not square with data on labor force entrants. It is quite possible that many or even most of these three million workers should in fact be counted as “discouraged” if not in fact unemployed. They certainly did not “retire” in the sense of their jobs being maintained and their being replaced by younger workers; indeed, some six million jobs have disappeared since the onset of the late recession four years ago.

What Does All This Mean for Equities?

One month of sub-par data, at least matched against expectations, should not be cause for alarm. And yet, in spite of the heroic entrepreneurial business class in America creating more than four million jobs since early 2010, one does have the sense that there is still a preponderant level of what Professor Higgs called “regime uncertainty” about the U.S. economy. The weak dollar, a product of long-running monetary manipulation by the Federal Reserve, is certainly a big driver of this ongoing (investment-killing) uncertainty, and is only augmented by other errant policies including the increased government spending and debt levels, and continual stream of new regulatory burdens foisted on the U.S. economy by the political class.

What this adds up to, unfortunately, is the potential for years of a “sideways” market for equities in the United States. Individual industry segments in which the U.S. lead is knowledge-based (e.g., information technology, biosciences, advanced capital-intensive and engineering-intensive manufacturing) will continue to outperform the broader indices, as will individual companies (e.g., Apple Inc. [AAPL]) with great managements and solid ability to execute in delivering excellent value-added products or low-cost offerings. But in a world where GDP growth should hover in the 2-2.5% range for an extended period, and where future tax increases seem axiomatic alongside a vacillating dollar and increased regulation and costs for most businesses, there is limited upside for the market as a whole. For the rest of 2012, a muddling-through in the Eurozone and in China, along with avoidance of renewed military and naval conflict in the Middle East coupled with further monetary easing, should suffice to keep U.S. equities in the black for the year, even given mediocre economic performance as depicted in the high-frequency data. We also think investors may anticipate better policies in 2013, including a roll-back of scheduled tax increases depending on election outcomes, and this will aid in equity values in 2012 if so.

But Americans, investors and consumers alike, must be forewarned: the Japanese know better than most the bitter fruits of massive Keynesian spending programs that run up government debts as a percentage of the total economy and destroy scarce capital, all in an effort to chase a phantom problem known as the “liquidity trap.” That is to say, the real problem in Japan, as here in the United States, is the growth of government at the expense of the entrepreneurial, dynamic, job-creating and wealth-inducing private sector. As goes the famous Japanese proverb: “Sow the wind, reap the whirlwind.” It is nothing short of tragic that Mr. Bernanke, who knows economic history so very well, has evidently learned some wrong lessons. A fretful world awaits the dawning of growth-inducing policies in the United States, starting with a dollar once described as being “as good as gold.” In such a world, mutatis mutandis, all sorts of good things then follow, including jobs.

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, John Chapman can be reached at john.chapman@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com. The views expressed here are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect that of colleagues at Alhambra Partners or any of its affiliates.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

Stay In Touch