By John L. Chapman, Ph.D. Washington, D.C. May 28, 2012

The current debate in Washington over fiscal policy parallels that of the Presidential campaign: how do taxes and government spending affect the economy? Does more spending “grow” the economy, as modern-day Keynesians suggest? Can progressive tax increases benignly cut any government deficit? Both theory and historical evidence suggest otherwise.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal last week, former Fed Vice Chairman and current Princeton University economist Alan Blinder asserts that the growing fiscal deficit is an issue to be worried about – but later. For now, he says, the current expansion in the U.S. economy is too “fragile”, and cannot be sustained “on its own”, meaning, via private sector-led activity. Professor Blinder wants more “stimulus” spending, particularly on infrastructure projects to build roads and highway bridges, in order to create jobs as rapidly as possible. He warns that a “fiscal cliff” will be breached if the Bush tax cuts expire (which, interestingly, he has advocated in the past) and the $100 billion in spending cuts due to last summer’s “budget sequester” deal are effected, and the Congressional Budget Office agrees: last week the CBO issued a report predicting a recession in 2013 if current law is retained.

Mr. Blinder’s Princeton colleague, Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman, is equally convinced that more spending is needed: at least $2 trillion more is immediately called for, and he is willing to countenance a great national lie to rally support for such massive new spending, similar in his mind to the exigencies of World War II. So federal spending, which jumped from 21.8% of GDP in 2008 to average 24.7% in 2009-2012, and the $5 trillion pile on in additional debt in these four years has not been nearly enough, for Mr. Krugman.

The Keynesian Mindset: Spending Begets Increases in Aggregate Demand Which Beget Wealth Creation

Messrs. Krugman and Blinder are two of the world’s foremost modern-day Keynesians. They believe, as Keynes explained in detail in his 1936 book, that government spending induces increases in demand, which raises incomes, which in turn leads to private sector spending. Thus, government spending acts as a catalyst for wealth and job creation, and this in turn should lead to advancing stock prices. Further, these modern acolytes of Keynes ignore Federal Reserve policy in recessions (or, per the current moment, anemic and “unstable” recoveries) and, like the master himself, believe that monetary policy is both ineffective and inconsequential when demand for money is high, and signals a preference for liquidity over risk-taking (borne of spending).

Lastly, the Keynesians adhere to their intellectual forebear’s distinction between short run and long run effects of policy, and for the most part hold his disdain for the longer term. Deficits are a problem, “in theory”, but can be solved at a later time when the economy is healthier. The question is, how correct is this vision in its modern context, and what, we might add, are the effects on stock and bond prices?

Fiscal Policy Effects in the Current Era

We have already addressed the efficacy of government spending several times in recent months, notably in defending the seminal insights of Jean-Baptiste Say, and especially the axiom named in his honor, Say’s Law. In short, Say held that production was the source, or cause of, demand; spending is an effect of (prior) production, and not a cause of economic activity unto itself. The distinction is a crucial one, because understanding the causal chain of events in terms of how wealth is created and leads to job and income gains fosters correct policies. Spending for spending’s sake, Say argued, might actually destroy the capital that begot the very wealth being sought for the entire economy.

With this as a backdrop to our analysis, we note the following key points about how the fiscal policy debate will play out this year, and how it will impact U.S. equity and bond markets:

(1) The myth of Fed and Treasury (or, Monetary and Fiscal) separation. Conventional wisdom about the political economy of the U.S. holds that our central bank apparatus, the Federal Reserve System, is entirely separate from the rest of the U.S. government, and independent of any political influence. At one time that might have been true, but after the demise of gold it is not remotely so – the distinction between monetary and fiscal policy is now an academic point that is moot. During World War II the Federal Reserve agreed to support U.S. Treasury funding of the war via massive purchases of U.S. federal debt, while domestic inflation was kept in check via extensive price controls and rationing. This led to major double digit inflation in 1946 (18%) and into 1947, and by 1948 there were renewed calls for Fed independence and emphasis on dollar stability. The resultant 1951 Fed/Treasury Accord affirmed Fed independence, but within 20 years Fed purchase of U.S. government debt seemed to be so strongly correlated with increases in federal spending that a whole new academic literature sprang up in macroeconomics on political business cycles.

However true the theories of political class manipulation of economic policy for electoral gain may or may not be, the unremitting reality is that today, Fed and Treasury actions must be analyzed in tandem if not as a whole. They are, effectively, cheek by jowl in de facto Fed monetization of U.S. government debt in a quasi-permanent way. We have to analyze it all as a whole now. Any casual observer in Washington can see this plainly: career officials often trade positions between the two, and in the most recent two Administrations, the Fed Chairman and Treasury Secretary have been in close touch, often coordinating on policy (the current U.S. Treasury Secretary is a former President of the New York Fed – that, after having worked in the Clinton Treasury Department).

This leads us to our first important policy conclusion: higher levels of government spending, often seen in tandem with Fed/Treasury coordination, lead to higher levels of unemployment and pressure on both GDP growth and stock prices. Unemployment in the U.S. averaged 4.5% between 1950-70, but increased to nearly 7% in the following 15 years. Between 1985 and 2008, unemployment retreated to 5.5% on average, behaving particularly benignly during the Clinton Administration, which produced four balanced budgets and a decline in spending as a share of GDP to levels not seen since the early 1970s (18.2%). Unemployment has exploded along with federal spending since 2008.

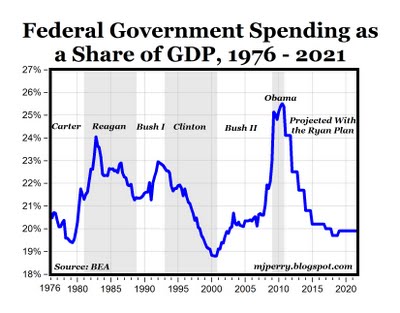

Indeed, the ratio of federal spending to GDP, which is a “normalized” way to look at fiscal spending across time, shows the detraction to economic growth and the concomitant stagnation in stock market gains when viewed across time. Economist Mark Perry has the relationship graphed back to 1976:

Chart I. Federal Spending as a Percentage of GDP, 1976-2021 (Estimate)

Source: Mark Perry, Carpe Diem blog, 2011

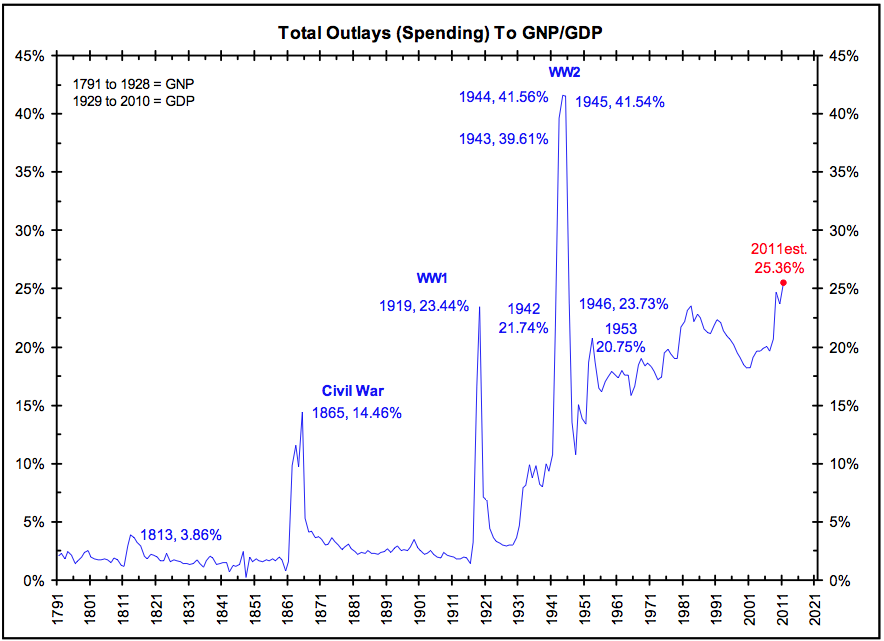

For those seeking a longer term view, Barry Ritholtz goes back to the Presidency of George Washington, to show how wartime spending at the federal level affects the ratio:

Chart II. Federal Spending as a Percentage of GDP since 1791

What the data show is that in peacetime, the greatest non-inflationary booms occurred during the 1920s, 1980s, and 1990s, while this adjusted fiscal spending was declining. In modern history especially, the 40 million jobs created under Presidents Reagan and Clinton, alongside 3.6% real GDP growth and rising incomes, give lie to the notion that government is needed to stimulate the economy via spending.

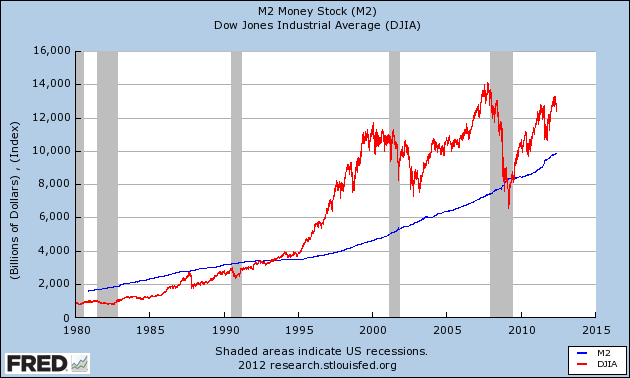

(2) The lack of a positive relationship between federal spending (or, “increased aggregate demand”) and real economic growth pertains to monetary policy as well. Conventional wisdom holds that U.S. equity markets correlate positively with changes in the U.S. money supply, and indeed, seemingly trade that way in the short run: by extension, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke has made no secret of his belief that well-timed quantitative easing can support economic growth as well. But in fact, looking at correlations between M2 and stock prices over intervals up to 13 weeks shows a slight negative correlation or, for our purposes, absolutely no relationship that would buttress calls for spending stimulus that is abetted by monetary easing.

In the long run, stocks and money growth have both been positive, but the relationship is not one on which to base any policy, thanks to the vagaries of shifting money demand (again, “liquidity preference”, for Keynes) that are oft-ignored by modern Keynesians:

Chart III. M2 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average Since 1980

Taken as a whole, what the empirical data tell us is important for both investors and policy-makers, both of whom would do well to pursue plans with a long-term time horizon in mind: fiscal spending stimulus, regardless of whether it is supported by monetary ease or not, does little to engender or sustain recovery, and/or affect stock prices.

To be sure, individual sectors such as, say, defense/aerospace, or suppliers to government real estate development projects or training programs that are expected to be the beneficiary of the new spending, get a lift. But as a whole, the economy does not respond to macro-stimulus programs.

(3) Markets appear to portray a “learning effect” with respect to policy, both fiscal and monetary. We do agree with Professor Blinder’s contention that short term policy effects that are akin to a “shock” that is unanticipated can have real effects, but these dissipate quickly and seem to decline over time as markets exhibit the theoretical predictions of rational expectations models (as developed by, among others, Chicago Nobel Laureate Robert Lucas). So, for example, QE1 was likely to be more of a market mover than QE2, QE2 than QE3, etc. (unless, of course, QE3 were totally unexpected because expectations had shifted the other way; in any case, not even QE1 seemed to have an appreciable effect on economic performance (though, as the first big monetary easing that had not been wholly anticipated, it did lower long term interest rates). The same is true of repeated spending stimulus programs, as Japan’s ten rounds of spending upwards of $2 trillion across the ‘90s and early ‘00s proved. This result, seen across several countries in the modern era, seems to place limits on the efficacy of government policy.

(4) The above evidence suggests policies that incite production will be more ameliorative to growth than policies geared to spending. This in fact explains why, empirically, cutting marginal tax rates that are sensitive to investment (viz., that promote productive output) have yielded clear-cut gains in economic output, vis-à-vis the more ambiguously-understood spending programs.

With that as a preamble, where are we with US fiscal policy and how might it affect markets and the economy rest of the year?

(a) It would appear likely that markets have not digested the likelihood of $494 billion tax hike now on the books for January 1, in which capital gains tax rates increase from 15% to 20%, qualifying dividends jump from 15% to 39.5%, and the highest marginal income rates go from 35% to over 42%. Nor have they affirmed maintenance of current tax rates, or what a President Romney might do. Equity markets in the U.S. will move once this is given clarity.

(b) Spending sequestration totaling more than $100 billion next year is unsettled as well, as is the fate of the payroll tax rate change. Our view remains that if the “Bush tax cuts” are repealed per current law, there will be – as the CBO has now stated – a very big slow-down at the least, and a hit to U.S. equities next year.

(c) Related to this, short term, impasse over US debt ceiling of $16.4 trillion, set to be crossed in next 6-8 months, is a potential threat to US equities — this has likely not been discounted yet either. Currently we are at $15.7 trillion. Markets hate uncertainty and, per the above historical data regarding the Reagan and Clinton eras, do not like government spending increasing ahead of GDP growth, either. While it is likely another deal will be brokered, all the chatter will increase nervousness in coming months and be a countervailing force to a positive lift gleaned from hope for pro-growth policies in 2013.

(d) Longer term, the U.S. fiscal path still heads toward a disaster and/or debt repudiation and commitments broken. There is no other end, given the budget math’s irremediability. Laurence Kotlikoff of Boston U. does an interesting calculation on total unfunded fiscal gap between now and 2075 — not only the bankrupt and bankrupting entitlements, but also the rest of the federal budget that has been in deficit since World War II for about 61 of 65 years. At $200+ trillion in present value, it clearly means major repudiation or a shift in spending and taxes down the road, but likely not before cataclysmic 2008-like events, and/or, at least a long Japan-like torpor.

Kotlikoff’s inescapable conclusions confirm the empirical data collected in the Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff empirical work on fiscal indebtedness across 44 countries over the last two centuries, the canonical finding of which is that debt-to-GDP ratios in excess of 90% cut median growth rates by one percentage point and mean growth rates by four percentage point from prior history. While the federal spending trajectory must be curtailed, the GDP growth rate may be lowered even more by declines in investment and profits. At the least, growing federal debt – and the debt-to-GDP ratio – weigh on investor plans for the future; the mere prospect of higher taxes tomorrow curtails investment today, impacting equity prices today.

(Countervailing this negative long term thesis are new information, communications, and solid-state physics/smart manufacturing technologies that offer the promise of unparalleled gains in productivity in the new century – gains that could potentially rival the impact that the leading technologies of the 20th century had on progress. For these to reach their beneficial fruition, of course, pro-investment policies that include a strong dollar must be pursued in Washington – but in any case, are again, not yet discounted into equity prices to any great degree.)

Summary of Current Fiscal Policy and Its Impact on the Economy and the Markets

In short, the review of modern history does not lend support to the Keynesian thesis that spending stimulus is helpful to an economy in recession or experiencing a weak (and jobless) recovery (and we have discussed in the foregoing mainly the U.S. experience, but the result holds for developed countries in Europe and Japan as well). Further, equity markets are impacted negatively by uncertainty surrounding both the future direction of policy as well as its likely effect on growth.

The election in the U.S. this year may well devolve, at root, to a debate over the “Ryan budget plan”, promulgated by Congressman Paul Ryan, the House Budget Committee Chair, and President Obama’s ten year budget projection, which includes many of his policy initiatives. In either case, we are likely to see somewhere between $21 and $27 trillion in total US debt in 2023. And, economic growth somewhere in the range of the Fed’s 2.3-2.6% per annum forecast seems to be the best case possible given the chronically high debt levels and spending now, although Messrs. Obama and Ryan both forecast higher growth for their respective plans.

Given this, it is hard to fathom a 20,000 Dow by 2020, as NYU economist Richard Sylla has predicted. And this is before mentioning another pressure point on US equities even if the fiscal spending gap is moderated by slower growth in spending: the quality of spending has declined. As Jean-Baptiste Say would say, we have more “unproductive” spending today (meaning more “G”, to Keynes), and less productive spending (less “I”). The return of the historic long term GDP growth rate in the U.S. of 3.4% per annum is unlikely, given this; we may be looking at the average since 2000, 1.8%, or even less than Fed forecasts. This is a point central to our thesis that we are into years of a sideways market now, a la 1974-82 (when real GDP growth averaged 2.0% over nine years).

If the long term is mildly gloomy, and one in which the U.S. mimics Japan after 1990, what of the short term? We do not see “austerity” programs, wherever they are enacted, as hurting equities for anything other than the short run, though we do concede that, like monetary QE the opposite way, they may have a very short term impact (less than marginal tax hikes, which can materially and permanently impact the trajectory of equity prices). Indeed in the long run they may well be positive for equities, where they lead to a rationalization of resource use and allow for greater investment (perhaps accompanied by pro-growth policies re: tax reform, say, or a stronger dollar). This is so because it means, like the 1980s and ‘90s, the government footprint on economy declines in real terms, allowing for more resources directed into investment.

Having said this, the U.S. has historically rejected “austerity” programs, and instead relied on strong growth to negate recessionary periods of below-trend progress in output. And even the Ryan budget does not contemplate a down-sized federal government overall, much less in any big discretionary programs – only the trajectory of federal spending increases are slowed.

Given the high level of uncertainty regarding 2013 policy in the U.S., coupled with the continuing anxiety in Europe, and now slower growth in major Asian economies, the next several months will entail pressure on U.S. and, by extension, global equities. The U.S. bond market may achieve record highs this year, portending a rising rate environment in 2013 and beyond. What it all adds up to is, best case, modest US growth rest of year, solid if unspectacular earnings, and perhaps, based on 2013 hope in a pro-growth agenda, slightly higher valuation on U.S. equities. It continues to be, as more and more people are calling it, a “plod-along economy,” in which investors must be alert for special situation opportunities and stay well-diversified.

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, John Chapman can be reached at john.chapman@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com. The views expressed here are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect that of colleagues at Alhambra Partners or any of its affiliates.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

Stay In Touch