Thinking Things Over July 22, 2012

Volume II, Number 29: Why Stock Market Prospects are So Poor for the Long Run (But Why You Still Should Own Stocks) By John L. Chapman, Ph.D. Canton, Ohio

At age 79, Blackstone Capital Advisors’ Vice Chairman Byron Wien is one of the elder statesmen of Wall Street. He’s still going strong, however, meaning he’s never without opinions, and given his six decades’ worth of observations of everything from sustained booms to a once-per-century panic and global catastrophe, he’s certainly worth passing attention.

So it is of interest that Mr. Wien has recently opined that long run U.S. GDP will likely conform to Congressional Budget Office estimates of growth in the low-2’s, or 2-2.3% per annum on average. That is of course more than a point below the post-war and 20th century growth rates of 3.4% per year for the U.S. economy, and in fact conforms to postwar European growth rates that led over time to a significant standard of living gap with the United States.

For Mr. Wien, 2% GDP growth is actually “good news” in the sense that he does not think the U.S. can do much better than that anymore, given how “competitive” the world economy now is, and the necessary deleveraging that must ensue for some years yet. And in truth, 2% per annum moving forward would be an improvement on the 1.8% growth seen here since the Inauguration of George W. Bush, or the 0.8% of the last five years. There is further consolation for Mr. Wien in the belief that stocks have running room from current levels, given historically low bond yields.

Frankly, though we do not disagree with the likelihood of long term growth in the 2% range – or even below that, sadly – we’re put off by the sanguinity of Wall Street denizens of the likes of Byron Wien. He is correct about the “budget math” and its drag on the U.S. economy’s ability to grow. But he and his Wall Street confreres, who collectively have been so much of the source of trouble in an economy hampered by the umbilical cord between Wall Street and Washington – that people of Mr. Wien’s ilk were only too happy to help build and defend over time – are obscene in their acquiescence of current sub-par economic conditions. Because in fact, there is nothing written in stone that commands a 2% economy as far as the eye can see (remember, an economy growing at 2% per annum will be nearly a quarter smaller than one growing at 3.4% just 15 years from now). And there is something that smacks of a “let them eat cake” mentality for smug Wall Streeters to profess satisfaction at sub-par growth that portends enduring struggle for millions of hard-pressed working-class taxpayers, as long as it still comes with profit opportunities thanks to underpriced shares.

Indeed, while he is correct about the high potential for stocks to advance here in 2012, Mr. Wien is typically Wall Street-tone deaf with respect to U.S. equities, thinking of nothing beyond the rationale for short term moves up. For there is little in current policy that evokes confidence in the minds of global investors that conditions for growth can be sustained in the U.S., and hence merit an increase in direct investment here of the kind that makes a difference longer term.

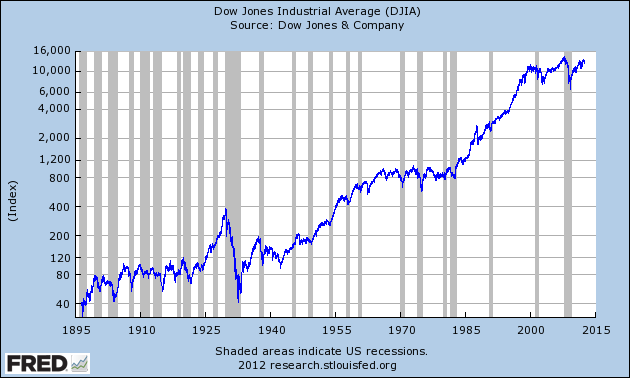

To see the problem starkly, consider the long run linkage between economic growth and U.S. equities. Chart I shows the Dow Jones Industrial Average since its inception in 1896 (in logarithmic form):

Chart I. Dow Jones Industrial Average, 1896-Present (Log Scale)

This single chart tells a big story about the U.S. economy (even though it must be admitted at the outset that it suffers from the usual measurement problems of all composite indices, especially those derived across time and subject to price-level aberration – and by definition, an apples-to-oranges comparison problem arises for an index that has changed 48 times in its 116 year history, where now only General Electric remains from the original group. Nonetheless, the Dow does afford us a decently-acceptable benchmark for U.S. economic activity across time emanating from an unchanging neutral observation platform). For our purposes today therefore, it is important to be reminded of two seminal points:

(1) Price-indexed U.S. Public Equity Gains Cannot Outstrip GDP Growth in the Long Run. The Dow Jones Industrial Average was calculated for the first time at the close of trading on May 26, 1896, finishing at 40.94. It closed on July 20, or effectively 116.2 years later, at 12,822.57, which works out to almost precisely 5.1% annual nominal gains in the index. We estimate that dollar-denominated purchasing power has eroded at an annual pace of 2.77% since May of 1896, meaning that, roughly, the Dow stocks have averaged about 2.3% discrete annual real gains for 116 years. This is below the roughly 3.4% continuous real gains in GDP output in that time (and so, the gap is likely not so great), and while the difference may be ascribed to either our own admittedly quick back-of-the-envelope figuring, measurement error from a roughly-hewn index measurement scheme or, if correct, due to inefficient public equity markets throughout much of this period, the point is that measured capital asset price gains do not systematically beat GDP growth. (Back-testing of the S&P 500 Index to May of 1789 confirms much the same result, as the nominal gain in the [artificially constructed] S&P across 223 years and two months is just shy of 3.6%, and real gains in the 2% range. Here, quite clearly, corporate equity gains would have lagged overall GDP growth in a time when other asset classes achieved superior returns.)

(2). Nonetheless, the Dow Jones Price Index Graph Shown above Highlights the Periods of Strong Growth, Borne of Good Policies Sustained Over Time. That is to say, there is a direct and high correlation between periods of strong gains in equity prices and a macroeconomic policy mix conducive to investment and output growth. The 1920s, the twenty year period following World War II, and the 1980s-90s were long periods of gains for stocks alongside periods of strong investment.

This is the dagger pointed at our economy today: investment peaked in 2006 and is still well below long term trend (the last deep recession in the U.S. the 1980-82 double dip, did see a return to the long term trend after pro-investment policy changes in full effect by January of 1983). And taken together, these two observations lead us to conclude that U.S. equities have a ceiling placed over them at the moment: GDP output in the U.S. does appear to be headed toward a long period into the future of a “new normal” of lower growth, and in turn, policy shifts to cause an inflection in this new normal do not appear to be in the offing.

There is however a silver lining to this story. The next graphic, Chart II, shows the total return to holding the Dow Jones Index basket of 30 stocks since 1987 – that is, the return including both capital value appreciation per the price index as well as dividends that were theoretically re-invested:

Chart II. Dow Jones Industrial Average Since the Fall of 1987, Comparing the Base Price Index Gains to Those Including Dividends

Courtesy of the Dow Jones Indexes blog Indexology, what the graph shows is that over this near-quarter century, when dividends are factored in, returns from equity investing are seen to be far more handsome than the nominal indices would indicate. In this time period, the DJIA Index itself grew about 6.5% annually in nominal terms – ahead of GDP growth in that time – whereas the total return growth is in the 9.5% per annum range. Even after loss of dollar-denominated purchasing power, then, owning equities has yielded in rough terms a 5% annual real return since 1987. And were we to carry this back further in time, indeed all the way to 1896, we would find the same result.

There is “good news” and “bad news” here for investors. The bad news consists in the fact that macroeconomic forces are – at present, anyway – aligned against the investor. Elections can be consequential for policy changes, so this may change, but even so, the extraordinary debt levels now burdening the U.S. economy coupled with forthcoming obligations imply higher taxes in the future, even if fiscal consolidation takes effect via lowered spending trajectory.

But the good news is that over the very long haul, owning stocks – especially those that pay dividends thanks to stable and/or competitively defensible business models – can be a key component of wealth protection, again, in the long run. Monetary instability, if not ruinous itself, certainly is unhelpful thanks to increased volatility of returns. And, the long run view of equity prices also shows that wars are almost uniformly not good for stocks, while they are ongoing (or at least, the pre-war trajectory for equity prices is lowered by the onset of war, and this can last years). But in the tortuous times ahead for the U.S. economy, history shows that stocks should ideally be a considerable part of any hard-pressed taxpayer’s personal balance sheet.

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, John Chapman can be reached at john.chapman@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com. The views expressed here are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect that of colleagues at Alhambra Partners or any of its affiliates.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

Stay In Touch