For most of 2012, Target II got most of the attention as a matter of interbank and Eurozone liquidity conditions. Target II liabilities built in the periphery (particularly Spain) as banks in the “core” withdrew from those sovereign debt markets. That left peripheral debt markets short of the liquidity needed to fund both public and private debt markets – credit prices became the very visible sign of potential euro disintegration. Conventional commentary since September 2012 has been that the reversal of credit pricing conditions posits a successful re-integration.

Money flows inside the ECB, however, tell somewhat of a different story. Some of this commentary will be clouded by the intentional opacity of the mechanics of central banking, but it is clear enough that the banking system is not on the leading edge of any price improvement. If that is a reasonable conclusion, then it also follows that interzone liquidity might also be equally dubious, only hidden into the recesses of accounting systems.

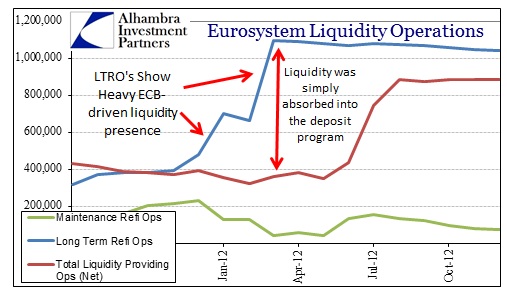

Since the first flare of sovereign debt (Greek) in early 2010, the backtrack of “money” out of integrated flow forced the ECB to take up the role of mediator against rollover risk in collateralized wholesale markets. The conventional fear of such mediation and balance sheet expansion is, as always, inflation, so some care was taken to manage the liquidity footprint of the ECB,

We must, however, always bear in mind the central banking conduit in Europe is actually a dual system. There is the Eurosystem of payments and joint operations of which the ECB is the head, and then there are the national central bank (NCB) “hubs”. Both ends play an important role in the accounting of “money”, and in fostering confusion. In the manner of liquidity flow, “money” originates at the ECB but is dependent on the NCB’s to direct it into the banking system and wholesale markets.

The LTRO’s, for example, were collateralized (loosely) arrangements where the ECB acted through the NCB’s to provide access to term funding. In the accounting, the aggregate amounts show up as liquidity providing “open market operations”. The dramatic increase in open market operations post-LTRO did not increase the overall footprint of the ECB or NCB’s onto the banking system. Total net lending did not increase at all since the net effect for the banking system was essentially a wash.

Banks in the periphery that were unable to find market financing for unattractive or unusable collateral used the LTRO’s to maintain operational financing, meaning there should have been an oversupply of collateral financing in the wholesale market place from “core” banks. These banks, as we well know now, simply parked their excess cash inside the NCB’s standing deposit facilities rather than create new interbank lending opportunities. Despite all intentions, the LTRO’s did not revive private wholesale markets.

This forced the Eurosystem into the middle of interbank intermediation, politicizing the liquidity distribution process. That meant that growing economic imbalances added to financial pressures to expand the chasm between North Europe and the Med countries. The starkest example of this, and what got credit market attention, was the eligibility “fight” over Greek sovereign debt. By May, Greek banks were forced out of the ECB’s programs and into the ELA.

ELA liquidity originates at the ECB (though there was a lot of confusion initially) as an autonomous liquidity factor since credit risk of ineligible collateral is absorbed by the NCB alone. As it was designed, the ELA takes in collateral that ECB open market operations shun. That, plus the relatively high penalty interest cost, makes the ELA a true last resort in the collateralized space.

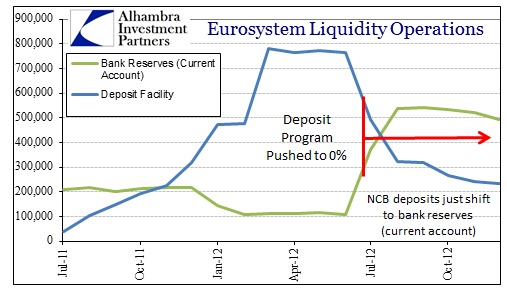

With the ECB squarely in the middle of a growing liquidity imbalance between geographic regions, it sought to “force” flow from core to periphery by eliminating the interest paid on the standing deposit facilities. The change succeeded in pushing funds out of the deposit facility, but only to move into the current account (idle bank reserves).

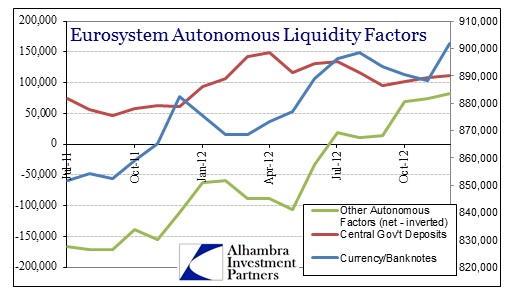

If the banking system were to absorb or repurchase sovereign debt across the periphery, we would expect to see dramatic movement of funds out of idle accounts. Instead, we see an increase in the “demand” for liquidity coming out of the “other autonomous” factors on the ECB balance sheet.

Historically, the primary driver of liquidity variability in the Eurosystem had been largely a function of national government deposits. Post-2008, however, we see the introduction of NCB factors pushing liquidity parameters. For the most part, the “other autonomous” factors driving liquidity demand inside the Eurosystem consists of the investment portfolios of the various NCB’s.

Since May 2012, these “other autonomous” factors have contributed to a EUR180 billion increase in demand for ECB “money” (and EUR250 billion since September 2011). It stands to reason that, absent a fuller description, NCB’s are involved in actively generating new liquidity in their own jurisdictions outside the more visible ECB channels. To what end? That is not answerable given the lack of active detail in these accounts.

The ELA was undisclosed before April 2012. Since that time, the ECB has put ELA usage into a separate line on its consolidated financial statement. Between May 2012 and December 2012, ELA usage only increased by about EUR23 billion. That leaves a lot of the NCB activity indecipherable in the current accounting context. It is possible that this relates to changes in foreign asset composition in the NCB investment accounts, but that would presumably get picked up at whatever non-euro counterparty is changing liquidity conditions (Swiss francs? Yen?).

What we do know is that something is driving liquidity demand (or the absorption of liquidity) at likely the NCB level in the Eurosystem. The last time such a large surge in “other autonomous” liquidity was noted was in September 2008 when “other autonomous” factors created a EUR218 billion desire for ECB “money” over the course of only two months. This latest move is nowhere near that dramatic, accounting to something like a slow leak in the Eurosystem.

The euro crisis has been proclaimed finished, but something is still amiss, buried within the vagaries of the dual-natured Eurosystem. These “other” accounts at various central banks are intentionally vague since central bankers want to be afforded the opportunity to create and advance liquidity in very quiet and non-distinct operations. That was the reason given for hiding the ELA inside another “other” account – the ECB was very concerned that disclosing it in an individual line item would create another panic phase (akin to the stigma of the discount window). I believe the ECB was correct in its interpretation of market reaction. The worsening turn in the euro and credit crisis was closely matched to the timing of the ELA disclosures.

Now that the ELA has been “outed” in the accounts, we are left to wonder what may have taken its place in the dark recesses of modern central bank obfuscation. That may not be know for some time, but we do know that banks (particularly those in the periphery) are likely absent from the recent credit euphoria and remain in a precarious liquidity position.

Stay In Touch