Joe should have known better than to ask, but for the sake of keeping this a blog post and not a full-blown research essay I will oversimplify as much as possible. In most media, the Swiss currency is treated like every other – as a function of, or tied to, the local economy. Thus currency moves are related to how the Swiss economy performs (a strong currency is proclaimed to be “bad” for Swiss exports). I think this dynamic is wrong for the Swiss franc, and that it is global finance that is the important variable here, not the domestic Swiss economy (and to some extent, this extends to other currencies as well, where finance is often the marginal determinant of currency rather than economy).

Conceptually, it is pretty commonly known that Switzerland is a banking center and that Swiss banks are disproportionately large. In fact, the two largest banks, UBS and Credit Suisse, account for 52.5% of all Swiss bank credit assets. However, that concentration is down from 69% in 2006, an important development in understanding the Swiss National Bank (SNB) and monetary/currency policy in Switzerland (extending into the rest of the global banking system).

Total bank assets in Switzerland are more than 6x total GDP. Even total credit assets are about 4.8x total domestic GDP. That means Swiss banks are taking in deposits across multiple large denominations that they then have to “intermediate” into “productive investments” globally.

Most global banks in Europe have been operating under the “hub and spoke” method of gathering local deposit liabilities and “investing” in global marketplaces, largely denominated in US $’s. Swiss banks were/are no different, except the additional complication of multi-denomination deposits at the outset. Bank managers themselves prefer to run matched books (at least from a risk perspective), but that isn’t a realistic goal.

The result is a mismatch of asset denomination and liability denomination, in addition to the now-familiar mismatch of asset maturity to liability maturity. There are also liquidity mismatches among the type of assets and the funding positions, but as I said above we need to keep this relatively straight forward. The bottom line is that Swiss banks are a tangled mess of global funding flow (not that anyone should feel sorry for the Swiss).

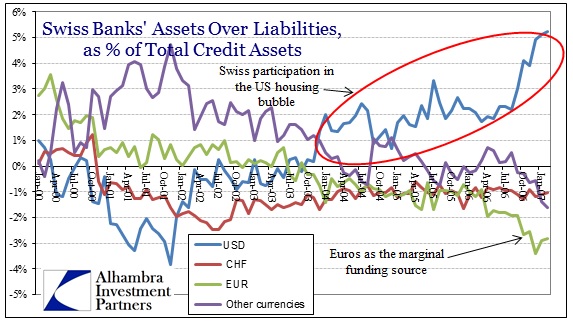

Across currency positions, as is shown below, the Swiss banks, particularly the big 2, were heavy participants in the US housing bubble.

By early 2007, Swiss banks had a USD mismatch of more than 5% of their total assets (that may not sound like much, but it was massive). Put simply, these banks had far more dollar assets than dollar liabilities. In the context of a bursting housing bubble in USD mortgage assets, that was trouble.

This is where it starts to get tricky. In terms of currency mistmatching, a rising USD, a trend that would persist throughout the crisis, seems to be a net positive to a huge USD asset surplus. If USD assets outnumber USD liabilities, and the USD is rising, this seems like a good situation since assets will rise faster than liabilities. So much so, it may seem possible that this mismatch can even make up for any additional losses incurred in USD terms.

But if we view this situation in terms of liquidity in addition to denomination, the scenario where USD assets outnumber USD liabilities is really a synthetic USD short. Because the Swiss banks are converting other denominations into USD’s, they have swapped out of those liabilities in other currencies into USD’s, and thus are short in USD on the closing leg of the swap. Since this was to the tune of more than 5% of total Swiss banking system assets, it represented a massive short position in a currency/asset regime that was becoming increasingly illiquid (USD mortgage securities). Since repo’s and other collateralized regimes were the basis for the denomination swapping, holding failing or unacceptable USD mortgage collateral compounded the issues. Therefore a rising dollar was not a good problem, it was potentially fatal.

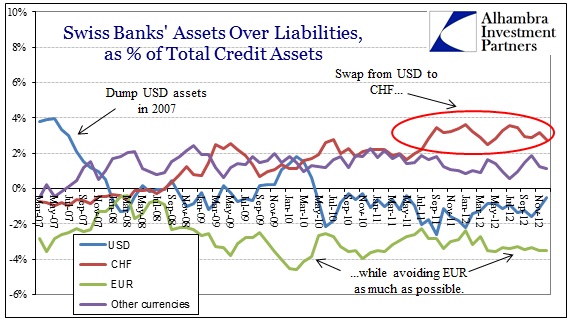

Fortunately for the Swiss, the SNB was proactive right from the start. Unlike every other central bank, the SNB saw the problem clearly and responded. Right away, in 2007, the banking system was directed to cut USD asset exposure as much as possible. In May 2007, Swiss banks held about CHF1.3 trillion in asset denominated in USD. By the end of 2007, that level was reduced by 16% as Swiss banks were actually booking losses. In the summer of 2008, the SNB nationalized part of UBS’ assets and began to recapitalize.

In 2008 and 2009, the size of UBS and Credit Suisse combined credit portfolio was trimmed by 38%, reducing the overall currency mismatch.

In the aggregate, Swiss banks began shifting, as many banks did during this period, from USD mortgage assets to local sovereigns. Fortunately for the Swiss banks, the local sovereign was not one of the PIIGS.

At the onset of the European sovereign crisis, “money” began to seek safety in the Swiss franc and the Swiss banks (due in no small part to the determined effort of the SNB to actually deal with the banking problem, rather than try to hide it). As deposits of largely euros made their way into the Swiss banking system, the currency mismatch changed from USD to CHF. That meant, in terms of liquidity, the banking system that was once short the USD to a huge degree was now long the EUR by an almost equal amount – out of the frying pan and into the fire.

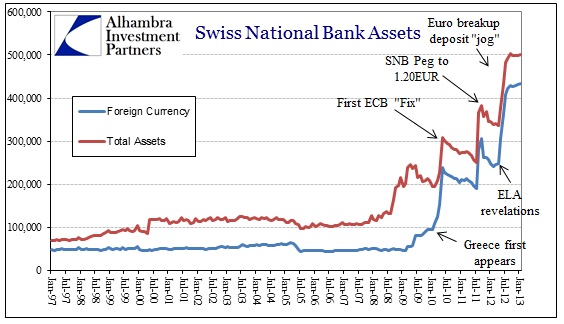

Thus, in my opinion, the SNB had the impetus to begin intervening in the EUR/CHF cross to slow the buildup of a synthetic long EUR position in its banks. The first visible sign of this mismatch was the dramatic drop in yields on Swiss gov’t debt. But the SNB also began to build its own positions in foreign currency, taking on the denomination risk itself.

And so it went throughout the ebbs and flows of the European debt crisis that remains unsolved even now.

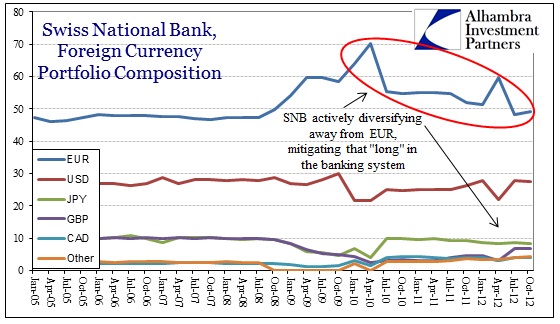

As I mentioned above, rather than have the banks take on denomination risk, the SNB has been actively manipulating currency flows through its own buildup and exchange in its foreign currency reserve portfolio.

Given this construction, the SNB’s actions should be viewed as a relief valve for stress in the aggregate banking portfolio arising from the diversified mismatch of denominations across assets and liabilities. In this context, the peg on the Swiss franc is likely to be a semi-permanent fixture for as long as new crisis points continue to appear (Cyprus being just the latest). The Swiss banks are trying to manage and reduce their exposure to the EUR on both sides of the balance sheet, but assets shrinking faster and farther than liabilities leaves that synthetic long in place – and will likely keep the SNB active.

As far was wider implications for global liquidity, I’m not sure the SNB really cares at this point. The purpose of its peg is to give its own banking system flexibility to remove itself even further from exposure to EUR assets. That will not be a net positive to short-term liquidity especially in EUR funding, but it will be a net positive to longer-term banking health. The SNB, opposite the Fed and the ECB, seems more concerned with the long game and is willing to take on the risks to get there.

If there was any doubt about that, in September 2011, Thomas Jordan, then Vice Chair of the SNB, gave a prominent speech in Basel arguing that a central bank can theoretically incur an unlimited amount of “losses”, and thus could endure large and extended “negative equity”. Given the safe haven status of the Swiss system, markets are likely to give them leeway if those needs arise. From the SNB and Swiss banking perspective, the peg to the EUR is in no way a problem; it is a solution.

Stay In Touch