Final revisions to Q4 2012 GDP were out today, with little surprise nor any major changes. Personal consumption expenditures were slightly lower, from adding 1.52% to GDP in the advance estimate, to 1.47% in the first revision and finally down to 1.28%. To underscore just how weak these figures are, real gross domestic purchases (the purchase of goods and services regardless of country of origin, and thus an overall metric of total consumer spending) amounted to 0% growth in Q4, down from 2.6% in Q3.

Offsetting consumer spending was a pickup in the growth rate of business investment. Originally estimated to contribute only 1.19% to GDP, the final estimate shows a 1.69% contribution. These are independent numbers from inventory, and so they have driven optimism that businesses are willing to invest even in this lackluster consumer climate.

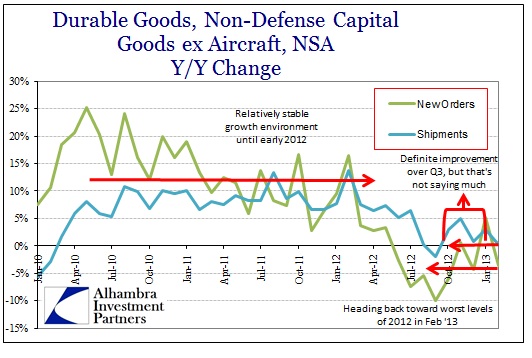

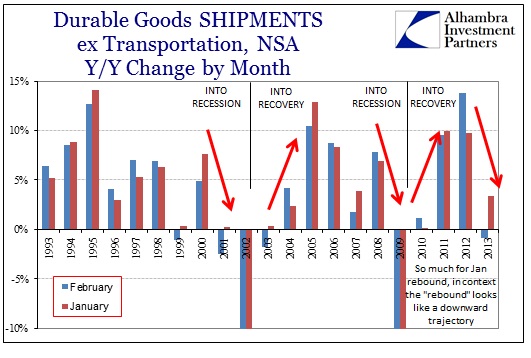

Some of that optimism was carried into the durable goods sector as January 2013 estimates indicated a potential rebound, and perhaps forward momentum for businesses and capital expenditures from Q4 ’12. While the change in the growth rate is certainly evident, in direct context it isn’t nearly as impressive.

Further, any positive momentum in January was erased in February as orders and shipments (outside of aircraft) sank again.

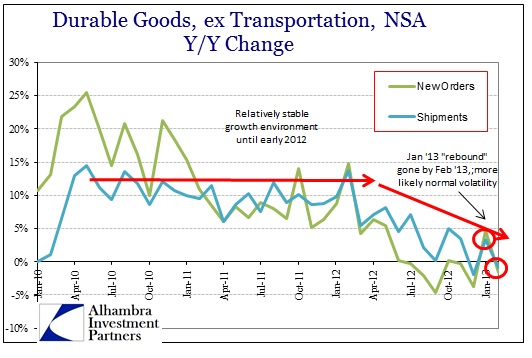

What looked like a potential rebound now looks like “normal” variance around the downward trend that was established in the spring of 2012. That trend/pattern remains unmistakable into February. From this perspective, business investment looks overly cautious rather than optimistic.

Looking at year/year changes, the first five months of 2012 seemed to be within the defined “recovery” trend, but so far in 2013 that is not the case.

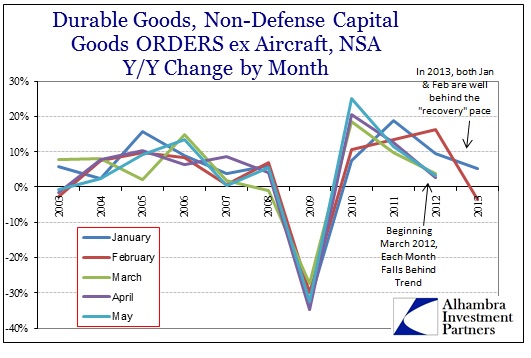

Not only for durable goods, but the capital goods sector as well.

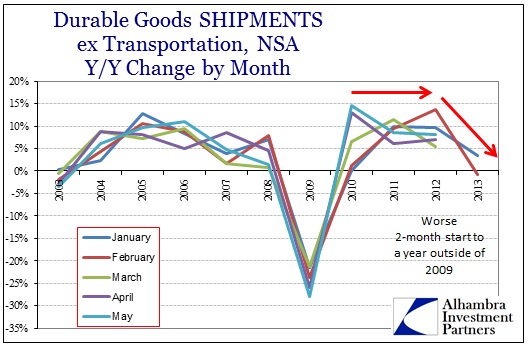

In fact, despite January’s general appearance of a “rebound”, in the fuller context of economic trends that rebound again looks like normal variance contained within a well-defined downward channel. The first two months of 2013 do not conform to the established growth of either the recent recovery/”boom” periods (2004-2007, 2011-2012).

While the change in growth is a bit better than 2010, the overall direction of economic pacing was certainly in the opposite direction then.

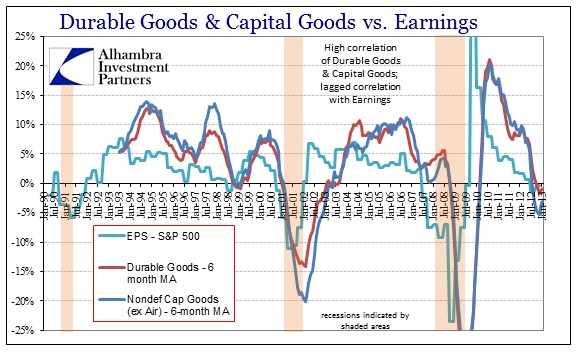

There really should not be such a mystery about this “unexpected” weakness in business expenditures (shipments) and plans for expenditures (orders). On an individual basis, businesses respond rationally to economic challenges. If they endure a prolonged period of weak revenue (due to consumer inhibitions) leading to eroding profits, you would expect individual businesses to reduce outlays – either labor or capital. Since labor was not fully utilized as an aggregate resource coming out of the Great Recession, it further makes sense that businesses would appeal to reducing capital outlays primarily (at first). Thus, as expected, we find a close relationship between profitability and capital expenditures.

Every instance where earnings fall sharply, durable and capital goods respond in kind (with a small temporal lag). The inverse also holds.

The most obvious exception, or at least the period where the lag was the longest, was the first half of 2008. In that period durable and capital goods held up despite a pronounced slump in corporate earnings. But that earnings recession (at least the initial part in the first half of 2008) was largely due to financial firms taking huge losses on asset write-downs, so there is some distortion to the real economy relationship in that period.

However, that raises a related point about the relative earnings level in 2012. We know that financial firms have been increasing earnings, and largely through the accounting measure of loan loss provisions, so it raises the possibility that earnings growth may have been distorted upward. If that is the case, then earnings and net income for firms in the real economy might be appreciably worse than they appear in broader, aggregate measures (such as S&P 500 EPS).

Whatever the true level of net income in the real economy, business spending is appreciably slowing and plans for spending are declining again after a brief respite in late 2012. Factoring in any inventory cycle that still may be effecting overall goods activities, there is a high likelihood that recessionary forces are already at work in certain economic sectors though they might not be fully apparent across the whole economic system (yet).

Circling back to GDP, for example, it wouldn’t be at all surprising to see an increased growth rate for Q1 ’13 as inventory levels look to be rebounding. But such variation is not at all inconsistent with the first phases of contraction (see Q2 ’08).

Stay In Touch