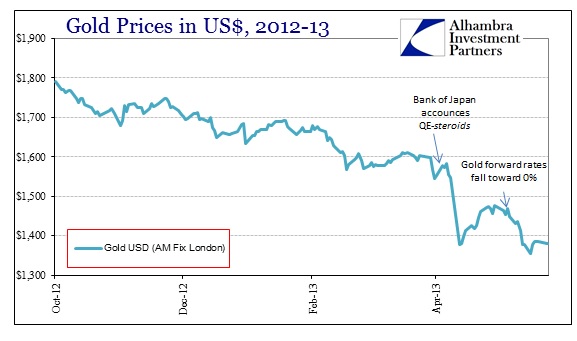

I have been espousing a theory that QE-steriods in Japan has led to a decline in liquidity conditions for Japanese banks. That, in turn, may have been partially responsible for the most recent downturn in the price of gold. It may or may not have been a factor in the gold smash of April, but at this point it cannot be ruled out either.

It is extremely difficult to define “blame” in the liquidity markets since there is an overwhelming opacity and dearth of reliable information on gold lending and even JGB repo relationships. Again, all we have are outside, second or third hand indications, such as gold prices.

I mentioned on Thursday that there has already been concern voiced over the extremely low haircuts in the JGB repo markets and how that might be a tremendous negative shock toward liquidity given the “surprise” spike in volatility. In a market that is totally unaccustomed to wild swings in price, the Bank of Japan now has on its hands a growing rejection of one “rabbit” of QE – low credit yields (the other “rabbit” being 2% inflation). It may become very difficult for banks to obtain liquidity if this environment persists since that will be a very visible sign that the Bank of Japan has totally lost control. Given that control is ostensibly the only grip holding the markets together, the outcome here needs little further illustration.

While GC repo yields in Japan have been very well-behaved, that too is not surprising. Again, published interest rates do not necessarily fully reflect behavior and conditions across an entire marketplace, particularly in markets that function over-the-counter with a high degree of bespoke arrangements. Effective liquidity may not be known even by the closest participants, including central bankers.

In the official minutes (which are highly edited) of the Bank of Japan’s policy meeting on April 26, 2013, there was a curious observation concerning JGB repo markets:

“Regarding the effects of JGB purchases on liquidity in the JGB market and the repo market, a few members, noting that the Bank had already relaxed the terms and conditions under the Securities Lending Facility (SLF), expressed the opinion that it should continue to deliberate on measures to prevent a decline in liquidity.”

That means that monetary policymakers fully acknowledged that QE is potentially detrimental to the wide dispersal of usable collateral. By loosening the terms of the Bank of Japan’s SLF, the bank intends on at least mitigating this problem via secondary measures, but, like the Federal Reserve’s emergency measures, liquidity is not the real operational goal of QE – it is all about psychology.

Negative liquidity, then, is a very real drawback or unintended consequence of QE. Now, the minutes of the meeting make no more mention of repo problems, nor do they specify the exact means of their concern. There are a couple liquidity issues here occurring simultaneously – the removal of collateral in concert with rising volatility. It seems from the minutes that the former was anticipated, but now the latter is also a pertinent problem that has forced the Bank of Japan to scramble to adjust its QE operations away from its primary objective (psychology) into a very real secondary objective (volatility).

Further, we have seen from other sources that the number of fails in JGB repos has spiked. That is a prime indication that liquidity conditions may be “failing” as well. Repo fails, one of the primary reasons for the panic of 2008 in dollar markets (especially eurodollars), are a visible sign that repo counterparties may be “valuing” collateral above “cash”. The reason for such a situation, as it was in eurodollars in 2008, is rehypothecation.

Where this intersects with gold in dollars is the euroyen* market and the Japanese bank participation in eurodollars. If we go back only to late 2011, we see that Japanese banks were the second largest users (as a group) of the Federal Reserve’s dollar swap operations. For various reasons, Japanese banks have accumulated large dollar positions, though not nearly as large as European banks. Therefore, liquidity problems in Japanese markets have an easy spillover into dollar funding markets, perhaps again with US money market funds.

It was US money market fund withdrawals from European wholesale money that precipitated the dollar illiquidity in Europe in both 2007/08 and 2011. While there has been no confirmation that this is happening again with Japanese counterparties, it would make some sense given what has transpired – and continues unabated to the point that the Bank of Japan itself appears on the verge of panic.

Again, liquidity, despite conventional wisdom, is not the aim of QE. In fact, in its most basic essence, QE is the desperate and intentional appeal to instability; with the caveat that central banks actually believe they can control it.

*NOTE: euroyen, as eurodollars, does not denote anything in relation to the euro or even Europe, it is a colloquialism that arose out of the physical location of this extra-regulatory wholesale money system. Since it was largely located in the city of London trading of bank balance sheet-created “dollars”, the “euro” shorthand was applied. So any wholesale market that operates outside of regulatory jurisdictions, a Wild West of banking, is often called a “euro” market.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch