It is easy to simply narrow the paradigm of the government showdown into party politics, thus pitting Democrats squarely against only Republicans. But that is only helpful in gauging political implications, should there actually be any (were there after 2011?). Rather than order the spectrum in terms of politics, it is more useful, for our purposes here, to align them via economics.

In that case they are all really indistinguishable. Surely, Republicans will object in that they oppose the nearly pure neo-Keynesianism of the ARRA and beyond, but the obvious counter is TARP. Further, the Republican side has fully embraced monetarism for decades, outside of the previously unheard libertarians. In reality, though, there is no real difference between neo-Keynesianism and monetarism. They are simply different sides of the same coin, now joined by 2008-driven circumstances.

It is easy for the Keynesians to embrace what is euphemistically called “monetizing the debt” as Paul Krugman, for example, has done on many occasions. Again, the monetarist side fits easily inside the Keynesian concept, and further both worship at the altar of “aggregate demand.” Neither fully contemplate, or even care about, the distortions on the “supply” side.

So the drama in Washington may be optically oriented to seemingly different views on government spending, when in fact they are really arguing about constraints and lack of success. In other words, had the dual Keynesian/monetarist approach actually worked as intended and advertised, this discussion never takes place. Robust economic growth makes deficit and outstanding debt a secondary or tertiary problem. It only takes on heightened importance due to the obvious incongruence between debt growth and lack of treasury receipts due to flagging economic fortunes.

The usual caveat applies here, in that government spending and overreach is certainly an important issue that needs to be addressed. But absent the overriding power of monetary power neither political side has really done so. This monetary facet is obvious in the relationship between total debt and interest payments.

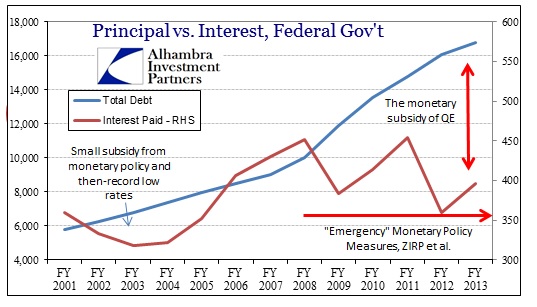

Total debt has risen 67% since the end of fiscal year 2008 (September 30, 2008). Over that period, total interest payments have fallen on an annual basis; from $451 billion in FY2008 to $359 billion FY2012.

As monetary policy wound its way through ZIRP and then multiple episodes of QE, the federal government was able to increase the debt level by two-thirds without adding any interest cost pressure – in fact, the Treasury Department has actually been saving money on interest costs.

This may or may not last much longer, but it should increasingly be a part of the discussion. For FY2013, through August 31, interest costs have crept back up again. The feds have already paid $395 billion in interest with a month left to go. That is already up some 10% already over 2012, and will be somewhere around 17-20% once Septembers figures are included.

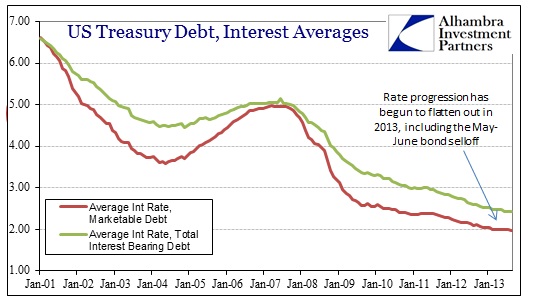

As you can see from the chart above, despite the selloff in bond markets beginning with taper talk in May, the average interest rate on UST debt has largely been unmoved. But therein lies the problem – without perpetually declining rates, total interest costs will begin rising simply due to the larger principal balance. The monetary subsidy takes the form of the second derivative in average interest cost. If that ends or recedes, interest payments being to increase in importance as debt is added in the absence of economic growth.

The argument about the Federal Reserve monetizing the debt misses the primary point. I wrote in January that,

“The politics of the debt ceiling really should be concerned with monetarism rather than focused solely on spending or deficits. But that is a hard position for either party to take. Democrats won’t because their interests are aligned with monetarism, while Republicans have at many times embraced monetarism with equal passion. Neither seems to want to move outside conventional economics that salutes as policy success a 64% increase in total debt without any perturbation in interest costs.

“We have not just a fiscal problem, but a persistent and massive monetary imbalance through dollar debasement that is directly related to both the debt disaster and the weak economy. Without directly facing it and working toward currency stability, we will be stuck with both the continued debt trajectory and no real growth. Neither can be adequately solved without first solving the dollar by ending capital repression.”

And that is the big trap. If monetary repression ends, so does the interest subsidy for the federal government – interest costs explode. That is the trigger, dependent on the monetary response to that fiscal trigger, to every hyperinflationary episode in history. That is not to say that I expect hyperinflation, but rather that it highlights the unfavorable position of the whole enterprise. We need growth, but cannot get it. To get growth, we have to (indirectly) end the subsidy, blowing up the budget. What then?

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch