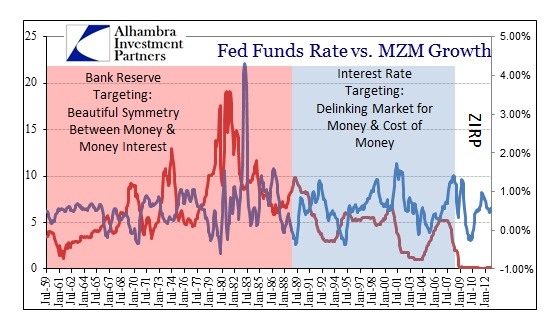

I’ve gotten a few emails asking for more detail on why the market structure seems to have changed or evolved since about 1990, particularly that relation to the Federal Reserve’s full implementation of interest rate targeting. Coincidence and correlation is not always causation, so it is useful to unpack the full chain of circumstances between them to get a better intuitive sense of how factors interact.

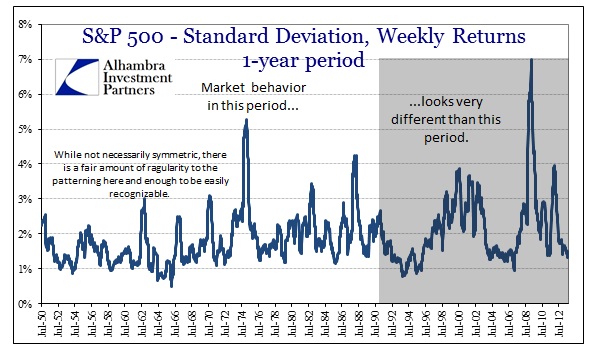

First, the character change in market structure stands out in the volatility series.

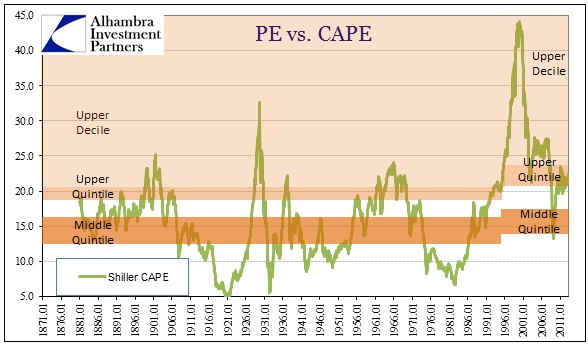

It’s not just the appearance of sustained low volatility periods, but the recognizable and nearly regular pattern of market episodes that shaped the pre-1990’s clearly morphed into something far less regular. That coincides with the rapid ascent in not just stock prices, but valuations.

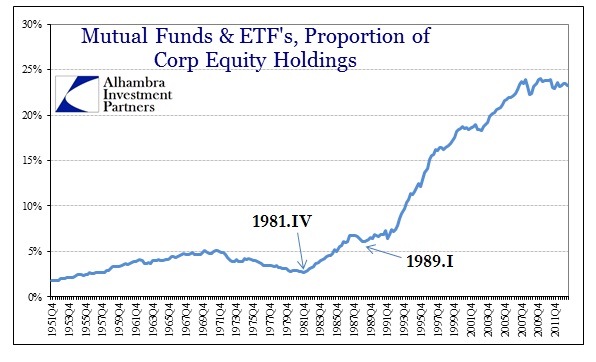

Around 1990, the market moved into the upper quintile of valuations and has only left it once (in the 2008-09 crash) since. One explanation, and a powerful one in my estimation, is the opening of the stock market to a broader section of investors through mutual funds and other “pooling” vehicles.

A sustained influx of “new money” would have to have some lasting or permanent impact on market structure itself. We should, under these conditions, expect these kinds of market “evolutions” which, on their own, are not necessarily “bad.” While it is relatively straightforward that such a sustained inflow would drive prices higher, appearing to be a good aspect of the evolving market state, however price history since 2000 suggests volatility may be more extreme and occurring only in shorter spaces (crashy).

The regularity of the incidence of volatility in the period before 1990 appears to have functioned as a kind of pressure release valve that kept markets from deviating too far from any sort of fundamental anchoring. The massive inflow of money in the 1980’s and 1990’s (especially after 1995) seems to have overwhelmed that safety mechanism, driving valuations far out of historical experience (and volatility with it).

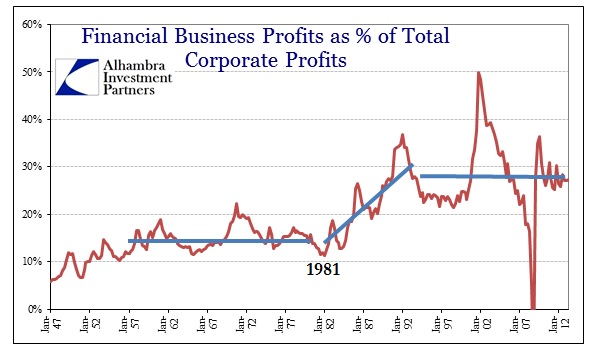

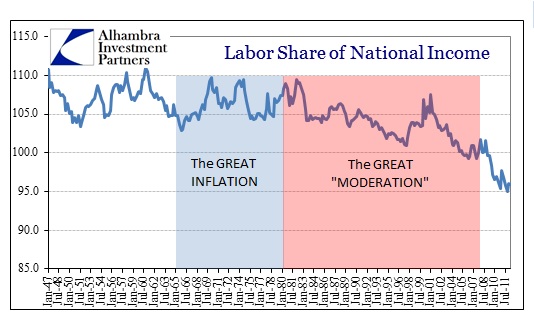

Alongside this monetary flow, we see the rise of financial firms in their relative place inside the real economy. That suggests a deepening financialization of not only credit production, but the monetary impulse itself.

Before the activist Fed took over in the late 1970’s, financial firms’ share of total corporate profits was usually around 13-15%. Since the early 1990’s, that share has climbed to between 23-28% (ignoring recessionary distortions). That could have only happened because of this:

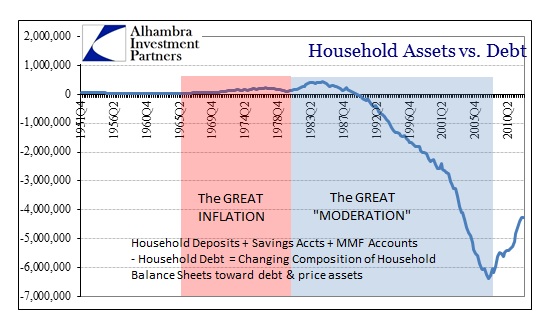

The flood of debt in the household sector drove financial profitability well past its historic norm, and it has stayed as debt has become more and more ubiquitous (and not just in the household sector – in every sector) since the early 1980’s. While the inflection occurred in the early 1980’s, making that decade a kind of transition period, it was after 1990 that imbalances appeared and festered. That was only due to intentional appeal to debt and credit by policy.

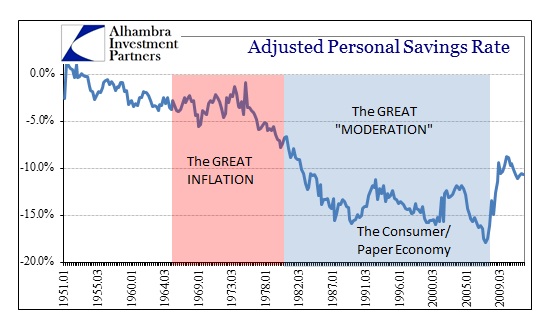

But in the household sector, the increase in debt usage and accumulation, while fostering financialization, also turned the economy toward consumption.

It was the consumer economy that, supplemented by debt, created the ability of households to use stocks as the primary marginal vehicle for savings. Without the growth in debt, spending patterns would have had to more closely align with earned income alone – meaning the ability to save through stocks would have been severely diminished.

It was these indirect effects that are largely responsible for these market evolutions – including the appearance of asset bubbles. Without interest rate targeting, where the Fed promises an unlimited supply of “reserves” to support its targeted rate, the saturation of debt could never have reached such proportions. Banks on a reserve target or with true money scarcity would have been much less sanguine about risk and balance sheet expansion. Interest rate targeting removed all apprehensions to monetary expansion through debt.

The implications of this creeping monetization are all around us, beyond stock markets. Not only have incidences of extreme volatility grown more scarce and more intense, the basic relationship of wages changed in a manner that we are wrestling with right now.

Orthodox economics proclaims that monetarism has no lasting impacts on the economy, proclaiming it neutral. That is clearly not the case given just the data I presented above – and there is much, much more. Something needs to account for the obvious changes in the market and economy since 1990.

That all of this occurred during the activist monetary regime, particularly under interest rate targeting, could just be coincidence. I sincerely doubt it given the growth and reach of debt into every economic and market corner. The saturation of credit explains these stark and complimentary changes far more than any other nonmonetary factor or combination of factors. Before 1980 these economic parameters were largely stable to the point of almost being self-regulated (which they were to a large extent through recession and volatility), but they are no more. The fingerprints of monetary intervention are all over these distortions.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch