If you haven’t discerned to this point, funding markets are incredibly complex and intricately linked across innumerable network nodes that make precise estimations, even analysis, equally difficult and complex. The primary nodule as it relates to global finance is geographically centered in London, as the eurodollar market largely operates there. With the “US dollar” as the reserve currency (I use the scare quotes here because there is nothing official or even much American about eurodollars as the US dollar, only the comparable denomination of measurement), it makes sense that eurodollars would play on outsized role in setting world financial trends.

At the other end of the spectrum, given the two decade plus decay set upon the Japanese system, it is somewhat counterintuitive to see so much emphasis on the yen. Most investors are at least partially aware that there exists a yen-carry trade, but that basic description does not account for the full participation of yen agents in the funding markets.

There is more than one way to supply “dollars” into funding markets, and each banking system has its own quirks and idiosyncracies that are relevant to dollar conditions. While the Japanese system was imploding in on itself in the 1990’s, Japanese banks began to fund their operations globally through the dollar system. If they couldn’t gain yen funding through deposits and invest them locally in Japan, they would use their infrastructure and legacy size to become, as did much of the rest of the developed world, dollar financiers.

This was most evident later in that decade as Japanese banks were forced to pay a premium in eurodollar markets, largely due to perceptions that Japanese banks were of greater default risk (with good reason, as the failure of several large brokers and banks during the Asian flu showed). Yet they persisted in dollar expansion despite this cost inefficiency. The reason was simple – they had to get out of the yen market or they would shrink with the yen economy. The only path to growth and expansion lay in dollar assets (or using dollars as a conduit to other currency systems).

That was the pathway that essentially opened the yen system to the carry trade, and it is the modern financial evolution that set about rendering modern economies as far more open systems than current thinking asserts. Orthodox economists still assume a closed system when approaching econometric modeling, and it is one of the greatest flaws (but certainly not the only) inherent to this overemphasis on simplifying variables. The Bank of Japan intends on “increasing the money supply” in Japan to “stimulate” the Japanese economy, only to increase the availability of dollars elsewhere in the world and in other asset classes. There is no mystery as to why five or six QE’s later and Japan is still stuck.

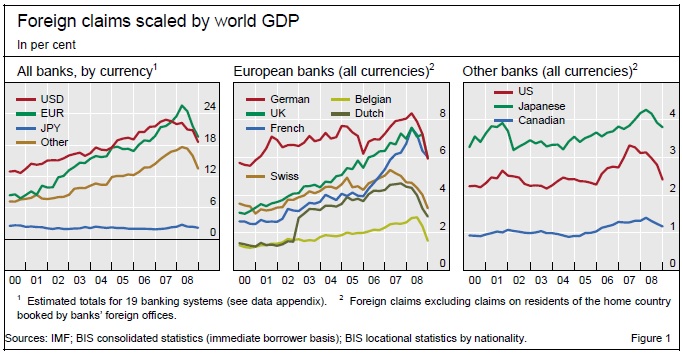

In the left-most chart above, the blue line indicates yen holdings claimed as “foreign claims.” Persisting so close to zero shows that there has been little interest in directing financial flows into Japan, instead remaining in dollars or other currencies (the carry trade).

Where does this yen funding flow? To US dollar markets, of course. This has nothing to do with either the US or Japan’s persistent current account imbalances, except to the extent that the Bank of Japan locates a fraction of its dollar surplus via deposit accounts with local Japanese banks. This is purely financial, and it represents how banking evolved away from traditional models to the shadow/investment bank system. It was a global revolution that is still largely misunderstood where it is even recognized.

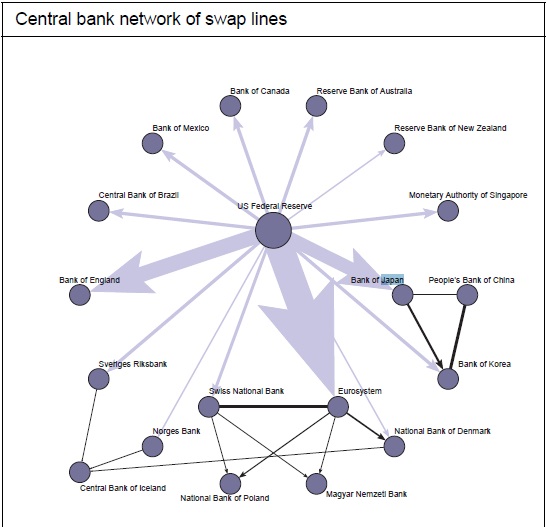

The Bank for International Settlements once tried to put a number on this dollarization through funding markets. The reason for that attempt was straightforward and very relevant to the times – the 2008 panic was a eurodollar panic brought about by this very dollar “short.” While convention largely centers on the European flavor of that panic, as it was the European banks that were mostly in the news and “bailed out” by dollar swap lines, Japanese banks were just as culpable, if not more so.

We find that, since 2000, the Japanese and the major European banking systems took on increasingly large net (assets minus liabilities) on-balance sheet positions in foreign currencies, particularly in US dollars. While the associated currency exposures were presumably hedged off-balance sheet, the build-up of net foreign currency positions exposed these banks to foreign currency funding risk, or the risk that their funding positions (FX swaps) could not be rolled over. [emphasis in original]

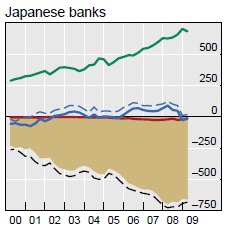

By 2007, the BIS estimated that Japanese banks had run a net dollar shortage of more than $600 billion, a truly astounding figure that really needs further context for that to be more apparent. That meant they supplied credit to the US system in the trillions, but funding for that credit was not always US $ liabilities. To gain a $600 billion short position required a huge commitment of local funding in yen, and then a robust derivatives market to transform yen into dollars. That is inherently risky on its face, but the global banking system relying on wholesale dollar funding of this kind was so heavily skewed to overnight and ultra-short funding that rollover risk was far greater than anticipated.

Notice in the image above that the Bank of Japan becomes a central node in supplying dollars further to other Asian systems. The Japanese banking system as a whole plays a crucial role in dollar flow in the east.

That is where eurodollar futures and interest rate swaps become so very important. The supply of “US dollars” on the global market is much more complex than interest rates and Fed policy. In this case, where JPY seems (conclusively) to be driving risk asset prices through the carry trade, volatility in yen affects the ability of Japanese financials to supply US dollar credit toward US risk assets.

The reason for that correlation with risk assets is the high proportion of dollars directed, by Japanese counterparties, to non-banks in dollar markets.

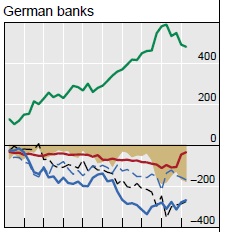

Japanese banks direct almost all of their net dollar positions to US $ non-banks (the solid green line above), funding that aggregate position almost exclusively via the cross-currency dollar short (the tan shaded area). Compared to German banks, for example, the absolute level of non-bank funding was and is much larger, and German banks relied much more heavily on funding via other banks (solid blue line) – Japanese banks were actually a small net provider (recycler) of dollars in the interbank markets (solid blue and broken blue lines).

Now this data is relatively dated in terms of exact figures and amounts, but it shows pretty well the systemic relationships and operational format of this dollar convergence across national systems. Japanese banks fund a high proportion of non-bank credit, funded itself on derivatives positions backed by yen; thus more susceptible to yen volatility even in relation to dollar volatility.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch