A full part of gold sterilization meant not just maintaining the total level of liquidity (though ignoring the distribution) but also in foreign “reserve” balances. The movements of gold created a trail of foreign exchange “reserves” which central banks around the world were using as tools to affect currency movements contravening of any gold pull or push. It was the exercise of “flexibility” that they believed was effective at offering some measure of management in the economy so as to not be so mechanically-driven by pure money market forces (gold). The desire of every central banker, past and present, is to be fully relieved of market pressures in order to conduct “enlightened” technocracy.

During France’s great gold pile accumulation, this can be seen clearly in what was a pretty typical transaction of that period (described by the Federal Reserve Bulletin of February 1928):

A slight decline in the gold stock in May [1927] was the result of a withdrawal of $95,000,000 of gold and a purchase by the reserve banks of $60,000,000 of gold abroad. Both the earmarking and the imports during May were largely the consequence of banking developments in France. The Bank of France in the course of the month paid off a debt to the Bank of England and thereby regained control of about $90,000,000 of gold which had been pledged as partial security for the loan, and had thus not been a part of the world’s available stock of monetary gold. The gold thus released was offered in the market, and $30,000,000 of it was exported to the United States on private account, while $60,000,000 was purchased by the Federal reserve banks and kept in London. Later in the month the Bank of France decided to convert a part of its rapidly growing foreign exchange holdings into gold, and for this purpose purchased large amounts of gold in New York to be earmarked for its account. In June and July the Federal reserve banks sold the gold held in England, and at first held the proceeds abroad, but later disposed of these foreign balances to purchasers in this country.

This is not to say that such transactions or “reserve” accounts did not exist before, only that the level of those reserves and the frequency in which they were transacted radically increased during the “sterilization” period. Exercising “flexibility” was often an act of these kinds of reserve accounts, foreign and domestic.

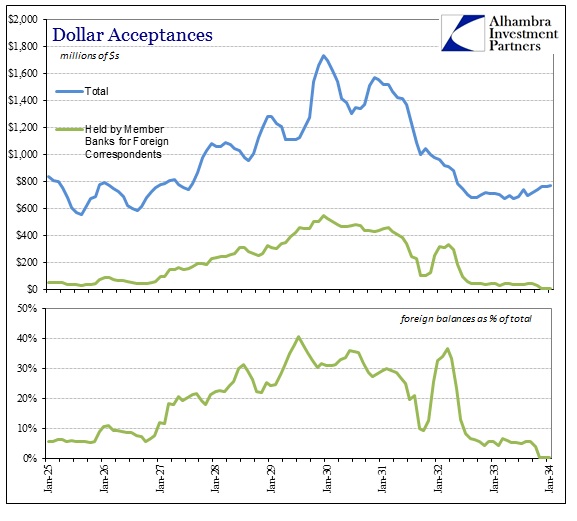

We can see these imbalances most clearly in the short-term money markets. In dollar acceptances, for example, the amount of funds placed in that market through domestic banks for foreign accounts rose conspicuously from 1927 right through to the Great Depression. This was the modern bank conception of not leaving deposit account balances idle earning nothing; better to place them in money markets to earn a return even in the case where such balances were reserves on account in foreign lands.

Between January 1927 and the peak in December 1929, the total acceptance market grew by $977 million (+129%), with half that rise accounted for by foreign correspondent accounts (reserves). Note that interbank behavior was being altered in both foreign and domestic actions.

But where domestic participation in acceptances was roughly equal, it was nothing in comparison to that other, more important wholesale money market – Street loans. Here we see the totality of central bank “flexibility” in the “golden age.”

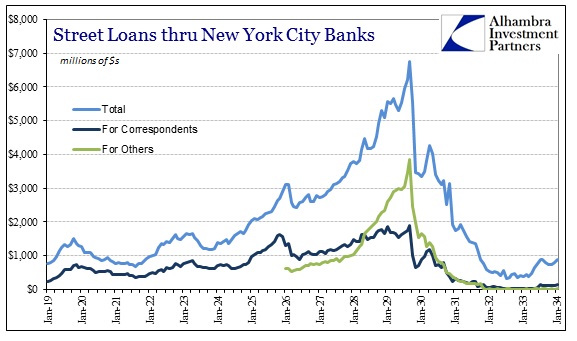

Prior to 1926 the statistics only distinguished between Street loans given on “own account” or “correspondent account.” The reason for any notation or separation is the pathways through which these otherwise “idle” reserves were put to use. Central city banks, nearly all in New York City, some in Chicago, were the channel through which call money was funneled. In other words, New York banks lent to New York brokers on behalf of banks everywhere. It was an efficient arrangement (at least on the way up) since the NYC banks were both the central liquidity axis (like modern primary dealers) of the whole domestic system and directly plugged into the call market.

As you can see from the green line in the chart immediately above, the Federal Reserve added a third category beginning in January 1926: “for others.” These were call money loans placed by NYC central city banks on behalf of nonbank entities, which included, as you may guess, foreign banks and central banks.

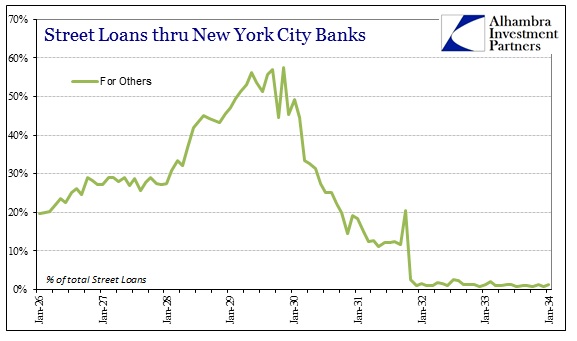

The green line above doesn’t do justice to the impact of “for others” on the call market, particularly 1927 and beyond (as a reminder, the PE on stocks began to rise precipitously at exactly this time). In terms of overall proportion, the flow of “for other” balances into Street loans accounted for nearly the entire increase in call money during the PE expansion/bubble period.

By the time the market crashed, the flow of foreign reserves (and other nonbank) reached an astounding 57% of all of Street loans in September 1929. Of the incredible $4 billion surge between January 1927 and the September 1929 peak, an unbelievable $3.1 billion (77.4%) came from “for others.” Note the timing of that proportional surge, right as the gold exports from the United States are at their heaviest.

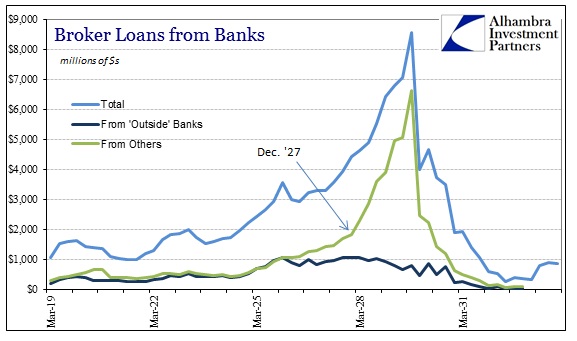

The other side of the balance sheet was, if you can believe it, even more imbalanced. While the level of Street loans presented above show the lending side, from the perspective of the borrowers, the brokers and dealers themselves, this trend and influence is even greater (NOTE: the difference in reported balances between Street loans and Broker Loans from Banks is the inclusion of all collateralized loans on the Broker Loans side, which includes other securities used as collateral, not just stocks).

The amount of call money reported as borrowed from banks by brokers and dealers surged to $8.5 billion right before the crash. That was an increase of $5.3 billion (+160%!) from just the start of 1927. Of that amount, all of it ($5.34 billion) was due to “from others.” What that meant was that foreign reserves were funding not just equity collateralized loans, though that was the vast majority, but also what amounted to a huge proportion, including more than 100% of the marginal growth, of repo-like credit positions in overnight markets (everything that happens has happened before).

Even the most unsophisticated of observers who might have no knowledge or idea about the arcane workings of 1920’s interbank and foreign account mechanics can see this plainly – that there is here a direct connection between central bank “flexibility” and call money. For an orthodox observer, I suppose the fact that this all takes place at exactly the same moment the stock market goes into overdrive to full-blown bubble proportions is just random coincidence. If you only look at consumer inflation and such price “stability” then none of this makes a difference. But, again, that narrow view does not account for how such a “golden age” could immediately and so easily collapse in on itself with breathtaking speed and destruction.

The Great Depression was no spontaneous destruction on the part of capitalism’s failure, it was the inevitable collapse of the intrusive foundation laid down by “flexibility” expressed into asset prices. The manner of that expression built up on a unsuitable foundation, with its cause not in gold but in countermanding gold.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch