The relative calm in China may have finally broken, as the latest ebb in the negative credit trajectory may have reached another inflection. It is well-known and established that the Chinese economy is heading toward what was only a few years ago thought to be recessionary (when 7.5% GDP growth was believed an indication of severe distress), to which commentary continues to sound expectations of another PBOC monetary burst. That expectation is just plain unfounded given how the PBOC has reoriented Chinese monetarism against “floods” that it itself admits only create bubbles (and thus artificial economic advance instead of real recovery).

That places the Chinese government in somewhat of a precarious position, which they may or may not realize and appreciate. On the one hand, they are undoubtedly aware of the huge financial imbalance that was created first to “address” the 2009 slowdown, and then another following the 2012 slowdown. However, it still seems as if most of the policymaking apparatus there believes that such imbalances can be controlled and managed even in a decline situation.

Earlier this year that played out as the PBOC “allowed” a couple of minor defaults; to which the “dollar” market recoiled and withdrew (rising “dollar”, falling yuan). Since that time, “markets” have been calmed by perceptions of “loose” monetary policy that has been anything but. Instead of “loose” in broad terms, the PBOC has gone forward with its new targeted approach (which economists somehow either missed entirely or allowed their bias to misinterpret). The results for Total Social Financing (a measure of broad credit growth in China) prove the changed stance of the PBOC:

The amount of new loans issued by Chinese banks fell by more than a third in October, adding to signs of faltering demand in the world’s second-largest economy which could prompt Beijing to unveil fresh stimulus measures.

The decline came after some banks reported bad loans rose at their fastest clip in two years in the third quarter, while deposits shrank, limiting their ability to lend and highlighting growing strains on the financial system as activity cools.

The first paragraph above illustrates exactly this mistaken belief and bias as the results of Total Social Financing in October are what the PBOC wants to see. In other words, “fresh stimulus measures” are not the coming result of TSF declines, but rather TSF declines are the result of this monetary shift. Part of that is, again, an idea that they can manage the decline with limited damage, as the alternative is existentially dangerous – reflating their various asset bubbles even further. It seems as if the Chinese government has made a conscious choice to at least address the bubble imbalance by not letting it go larger rather than risk it bursting on its own in spectacular and destructive fashion.

To that end, another bankruptcy is bracing China this week, this time in steel.

A reorganization application for the Wenxi, Shanxi province-based company was accepted by the Yuncheng City Intermediate People’s Court, according to a statement posted on chinacourt.org, a government site that lists legal proceedings. Creditors are required to claim their rights by Feb. 22, the statement said.

China’s slowing economy and the country’s measures to tackle pollution are taking a toll on its steelmakers already plagued by industry overcapacity. Haixin Group’s bankruptcy will be followed by others, according to researcher Mysteel.com Chief Analyst Xu Xiangchun.

“Instead of reorganization efforts conducted by local governments, this is an inevitable trend that China will take more ailing steel mills to the courts to protect creditors,” Xu said by phone from Beijing.

The global slowdown which looks to be more and more the end of the elongated cycle peak process is certain to roil Chinese confidence once again. That might be exacerbated as clearly “market” participants believe, if commentary is representative, the PBOC will ride to the rescue as it has always done previously. When they find out that isn’t the case, what then?

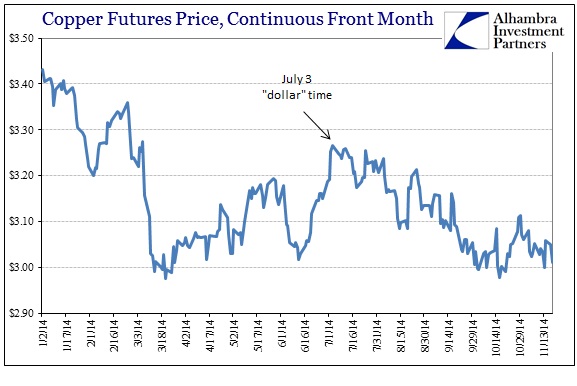

Copper prices have fallen since, when else, July 3rd in exact tandem with the global dollar “tightening.” That is different in form than the financial implications from the copper collapse earlier in February and March, suggesting that surface “dollar” disruption to China has been minimal throughout this latest period. Balanced against that theory are the rumors and suppositions that Hong Kong is once more the gateway to off-the-books dollar flow, meaning that the lack of visible response in the yuan/dollar exchange may be masking more serious deterioration in China finance alongside economic decay originating globally.

The net result is potentially another flare in the Chinese extension of the global growth problem. It is far too early to make any definitive estimate, but the recent and admittedly slight downward turn of the yuan against the dollar is at least curious in that regard. The mid-year calm may have run its inevitable course, as one more time investors need to be reminded of Zhou Xiaochuan’s positioned caveat:

“If the central bank is not a part of the government, it is not efficient in coordinating policies to push forward reforms,” [Zhou] said.

“Our choice has its own rational reasons behind it. But this choice also has its costs. For example, whether we can efficiently cope with asset bubbles and inflation is questionable.”

The last six months, especially the “targeted” approach to monetarism, seem to be following just that path, though most investors (never mind economists) don’t appear to have yet to caught on to it.

Stay In Touch