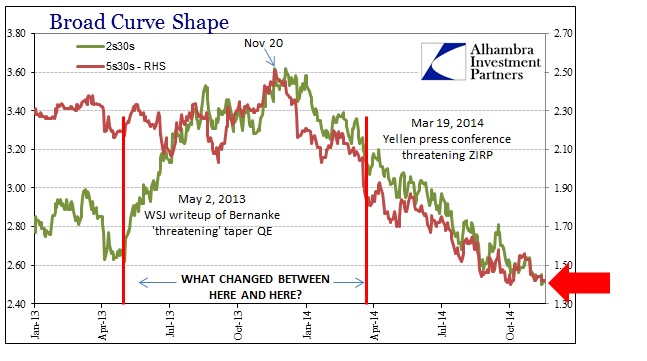

As the FOMC gathered only a week after October’s unusual UST “experience”, they faced an oddly familiar problem. The entire focus, at least externally, has been on how to exit extraordinary “accommodation.” Yet there is clearly a market difference between 2013’s discussions in that direction and 2014’s. As noted previously, credit markets in 2014 seem to be keenly aware that such “exit” is nigh impossible.

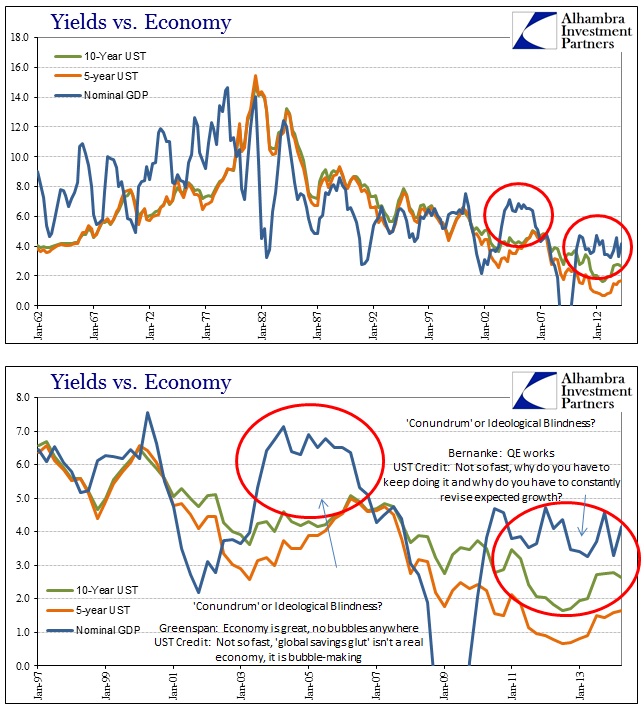

What makes this familiar is not just the relation of 2014 to 2013, but the last “tightening” episode of the middle of the last decade. A recent sit-down with Alan Greenspan seems to have brought out that now-infamous and now highly relevant “conundrum.”

“We wanted to control the federal funds rate, but ran into trouble because long-term rates did not, as they always had previously, respond to the rise in short-term rates,” Greenspan said in an interview last week. He called this a “conundrum” during congressional testimony in 2005.

The stupefied Fed under Greenspan could not relate their orthodox tendencies to actual credit market conditions. In the vacuum they reached for, as they always do, a convolution which attempts to address reality while preserving their orthodox paradigm. Enter the total and utter nonsense of Bernanke’s “global savings glut.” It was nothing of the sort, instead the changed condition of the growing global dollar short. In other words, the “printing press” for much of the housing bubble era (and even further back to 1995) resided not in the Marriner Eccles building housing the Fed’s DC HQ, nor the Open Market Desk at FRBNY. In fact, the marginal “printing press” of US$ credit wasn’t even domestic bank balance sheet capacity, but rather eurodollars.

If you think the world has a “global savings glut” in 2005, as Bernanke did, you aren’t going to be very constructive toward heading off a eurodollar panic less than two years later. The Fed got it very wrong throughout the whole of the crisis because they failed to appreciate, or understand, truly global shadow finance (which was, by then, to the tens of trillion of “dollars”).

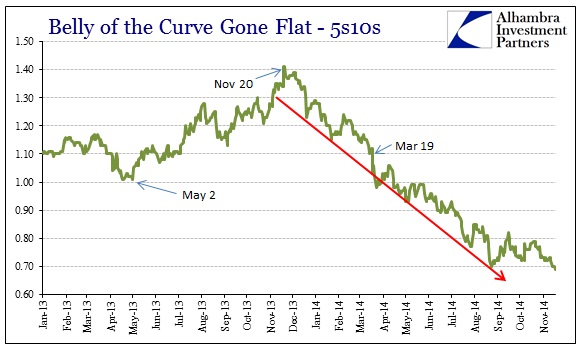

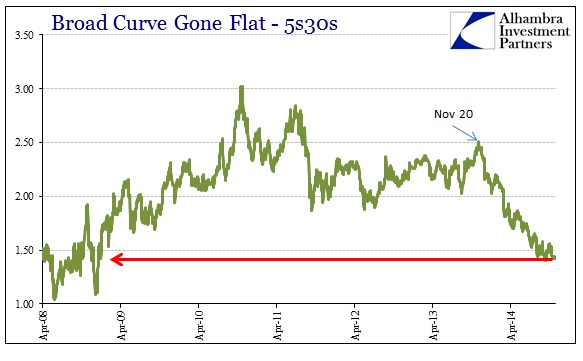

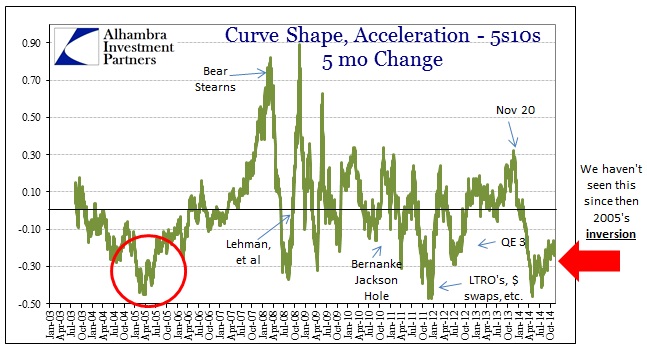

Now we see almost exactly the same setup in 2014, where long-term interest rates are not following the Fed’s intentions. If credit markets believed what the FOMC believes, then they would react this year as last year – steeper curve overall with nominal rates meandering upward. Instead, as 2005, the curve flattens, very bearishly, while nominal rates look to be contained by a ceiling or just move steadily lower (especially the outer years).

To that end, the FOMC is again pondering a 2014 “global savings glut” instead of looking toward wholesale “dollar” funding and the global dollar short. In fact, the only reference to “long-term interest rates” in the October FOMC minutes was this brief non sequitur:

Several participants judged that the decline in the prices of energy and other commodities as well as lower long-term interest rates would likely provide an offset to the higher dollar and weaker foreign growth, or that the domestic recovery remained on a firm footing.

Instead of looking at those “market” signals as potentially signaling, they judge them to be “stimulative” toward growth prospects? Again, “global savings glut” and “flow” from that mistaken idea does not explain, at all, the behavior and price of the dollar recently. To expect that is to be as befuddled as Bernanke in 2005, which is a very bad place for the FOMC to be right now.

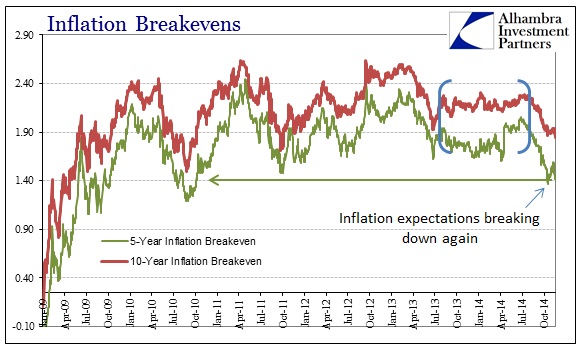

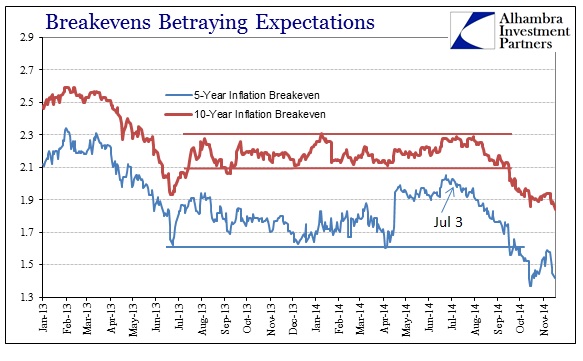

As if to confirm my supposition here about how inattentive they are due to blind ideology, the minutes make clear the FOMC remains equally confused as to why inflation expectations in credit markets are not behaving as “survey” results are.

Survey-based measures of inflation expectations remained well anchored, but market-based measures of inflation compensation over the next five years as well as over the five-year period beginning five years ahead had declined over the intermeeting period. Various explanations were offered for the decline in the market-based measures, and participants expressed different views about how to interpret these recent movements. [emphasis added]

Because the survey’s are “well-anchored” they remain unconcerned, instead offering “various explanations”, likely the same kind of convolutions as in the past, which simply means they can’t figure it out. How a statistically-adjusted poll is more compelling than the Fed’s own preferred metric of inflation “expectations” is confounding until you realize that they want to believe the surveys to the exclusion of what markets are saying (or, more precisely, they want you to believe that is what they believe).

The minutes recount how at least one committee member went so far as to doubt the veracity of market inflation measures due to some heretofore unrevealed liquidity constraints in TIPS.

The explanations included a decline in inflation risk premiums, possibly reflecting a lower perceived probability of higher inflation outcomes; and special factors, including liquidity risk premiums, that might be influencing the pricing of Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities and inflation derivatives.

I have certainly criticized TIPS indications myself, especially when inflation breakevens were conspicuously stuck in a tight range for about fourteen months. That is why you always look at what other measures and estimates are indicating for corroboration. In this case, the FOMC wants to dismiss TIPS and inflation expectations in credit markets despite a whole range of corroboration, including credit market segments that aren’t facing “liquidity risk premiums” (presumably), the price of oil and even just basic elements like a rapid retrenchment in global trade, recessions in Europe, Japan and maybe even China, while at the same time (perhaps these are all related?) the US can’t ever seem to generate any sustained and real wage growth despite the unemployment rate falling as it has done.

To which the FOMC minutes add that the committee judged these “market” indications would, in fact, be worrisome if they “somehow” suggested a weakening economy:

One participant noted that even if the declines reflected lower inflation risk premiums and not a reduction in expected inflation, policymakers might still want to take them into account because such a change could reflect increased concerns on the part of investors about adverse outcomes in which low inflation was accompanied by weak economic activity. A couple of participants noted that it was likely too early to draw conclusions regarding these developments, especially in light of the recent market volatility. However, many participants observed that the Committee should remain attentive to evidence of a possible downward shift in longer-term inflation expectations; some of them noted that if such an outcome occurred, it would be even more worrisome if growth faltered. [emphasis added]

It is not unusual to see the cart before the horse in these settings, but you would at least think the FOMC would have a somewhat basic grasp on inflation “expectations” since the whole of their paradigm centers on exactly that. That is why Greenspan’s “conundrum” is such an apt historical comparison, especially poignant as a reminder that these economists have no idea what they are doing particularly in relation to actual markets outside of the carefully constructed statistical facsimiles contained in their models. The models are given preference over markets, and where markets don’t follow the models they reach for all these backward and misleading explanations rather than admit what might be truly underway.

Apropos:

Many participants commented on the turbulence in financial markets that occurred in mid-October. Some participants pointed out that, despite the market volatility, financial conditions remained highly accommodative and that further pockets of turbulence were likely to arise as the start of policy normalization approached. That said, more work to better understand the recent market dynamics was seen as desirable. In addition, a couple of participants noted the potential usefulness of collecting additional data on wholesale funding markets in order to better understand how changes in interest rates could influence those markets. [emphasis added]

That is a euphemism for “wholesale funding markets are a complete mystery”, somehow still after seven years of being the epicenter, so it might be a good idea if some staff economist would run some regressions on them. It would have been useful to collect such “data” on wholesale funding in 2005, if not 1995, before Bernanke and Greenspan concluded that an unconfirmed and nonsensical “global savings glut” could allow them to see the economy as grandly spectacular and thus ignore markets that were more than suggesting artificial growth and asset bubbles. That also points to why the FOMC might just repeat the same tactics, as topical ignorance seems to allow monetary bliss.

To that end, market similarities between 2005 and today are instructive in how much credibility these orthodox sentiments contain. Then, as now, credit markets discounted “growth” as artificial and unsustainable, particularly in our recent “recovery” as clearly UST yields are not enamored with perpetual economic optimism.

Even though the yield curve can’t invert in this ZIRP environment, I doubt it would make much difference to counter inflation survey results that do what they are “supposed to.” It certainly didn’t in 2005:

FOMC in far shorter summation: everything is great except for every market indication, all of which are doing the opposite of what we expect. So we will, in good standing with past operation, just dismiss or ignore in continued favor of our models that don’t ever seem to match experience. This would be a Monty Python skit if it were not for the trillions upon trillions positioned exactly because of it.

Stay In Touch