Now that QE is history (for the fourth time) there are a number of misconceptions about what is taking place at the Fed. All the action is located at FRBNY, which only makes the tangled spread of accounting classifications that much worse. Interbank activity has never been much of a widespread, household concept, so the relevance to current circumstances only heightens the confusion.

Even among the more muddled commentary that has equated QE’s end with “tightening”, this stands out:

Despite a plethora of naysayers who doubt the U.S. economy is really gaining steam, the Federal Reserve is positioning its own investments for higher inflation and rising interest rates. As I predicted in August, once the Fed’s balance sheet peaked at just over $4 billion, oil prices began to plummet. The Fed dumping $259.2 billion in bonds in the last 90 days can only mean it is scared of inflation.

Forget any disagreements over subjective conjecture about implications and such, this is just mathematically incorrect (starting with the typo of $4 “billion” which should be “trillion”). The Federal Reserve is dumping exactly nothing, a fact so easily established that any contrary assertion can only be due to an agenda.

On August 27, 2014, the Fed’s total SOMA holdings amounted to $4,139,288,082,676.47. As of the latest figures, December 3, SOMA totaled $4,213,662,522,113.77; or a net gain of $74,374,439,437.30. The increase of $74 billion is due to a few factors, including that QE itself was not actually halted until October, but also that MBS prepayments and maturities are being reinvested. Of that $74 billion, $25 billion was of UST notes and bonds (no t-bills since Operation Twist recognized the damaging repo problems of taking too many bills out of circulation) and $51 billion MBS, with smaller asset categories making up the difference.

A central bank balance sheet is almost like a depository institution as it has two sides with assets and liabilities plus equity. It does not operate squarely on the same principles as a bank, obviously, as assets are how the central bank creates “reserves.” That is where QE takes place, as total “Reserve Bank Credit” for the Federal Reserve System (across the 12 branches) were $4.446 trillion as of December 3. That was up from $4.376 trillion as of August 27, meaning that the Fed’s balance sheet has, as its SOMA holdings suggest (but are not exhaustive, the Fed has other assets too), continued to expand, though at a much slower rate.

On the other side of the ledger, however, the central bank can also affect policy and bank “reserves” by what it calls “absorption” factors. The Fed can simultaneously extend QE-type “money creation” and take it right back via these absorption channels. That has been where the greatest points of contention have actually taken place since 2008 and for reasons that are not very clear even today.

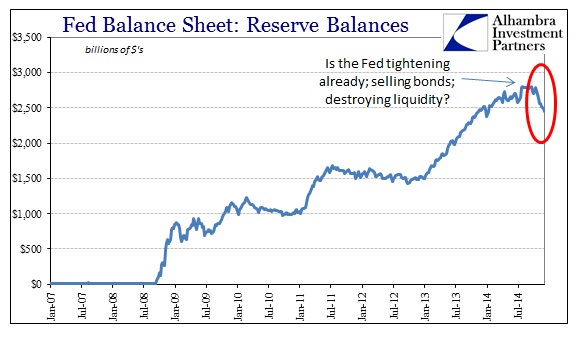

At the end of all policies is the net total, which is called “Reserve Balances with Federal Reserve Banks.” This is, as the name implies, where most people see the “printing press” (mistakenly, as bank reserves have little bearing on credit and liquidity conditions directly) as it presents the balance that banks show themselves. Thus, “reserves” have actually shrunk from August until now, dropping from $2.779 trillion to $2.449 trillion (-$329 billion). Maybe this is the source of the author’s mistaken designations from above, as it certainly might seem, fleetingly, as if a drop in reserves is consistent with “selling bonds.”

Again, that is totally opposite of what is taking place. The drop in reserves has absolutely nothing to do with QE or its end. This “absorption” side of the balance sheet contains two major programs, one of which has become more familiar – the reverse repo program (RRP). The intent here is to “soak up” excess reserves so that short-term interest rates remain on target or at least consistent with the policy mandate. That hasn’t really gone as advertised, so attention has moved to this other “absorption” policy, the Term Deposit Facility.

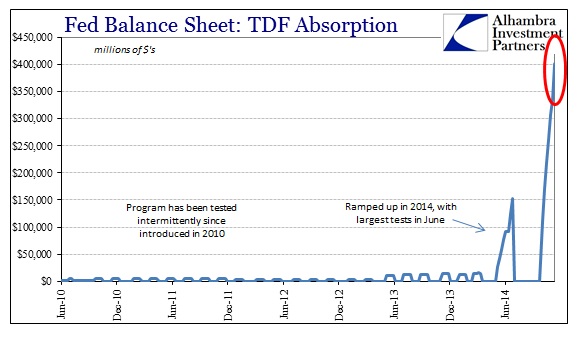

The TDF is essentially a companion to the IOER, except that it is seeking to “absorb” excess reserves longer than overnight, thus the usage of the designation “term.” The Fed has been “testing” the TDF since mid-October, scheduling eight weekly auctions which will conclude next week. Under the terms of the program, banks submit either competitive or non-competitive bids for an interest paying account for a term of one-week. Under the conditions of this test, banks are eligible to withdraw funds prior to maturity, but whenever the TDF gains full program status they will not be able to access funds without forgoing all interest in addition to a 75 bp penalty. That is an important distinction as, again, the intent is to “soak up” reserves.

The idea here is simply another means to accomplish what the Fed desperately wants – a durable floor under all interbank rates very much in recreation of the European system of a “corridor.” The TDF, in conjunction with RRP, is supposed to provide that.

Since the TDF and the RRP absorb reserves, the calculation for total bank reserves is this: QE adds about $74 billion in reserves between the end of August and the first week in December; the RRP removes an additional $14 billion while the ramped up testing of the TDF subtracts $334 billion (plus an additional unrelated absorption of $47 billion in the US Treasury’s general account). That leads total reserves to shrink by about $293 billion due to these three factors alone. With currency in circulation increasing by about $30 billion (which is an absorption “liability”), we have our total decline in “bank reserves.”

At first blush, we might be tempted to entertain the TDF as perhaps relating to recent liquidity problems, particularly as the ramped up portions closely align with key events. The first major test in June occurred during the first breakout of repo problems and the dollar rising. The second and larger test began October 15. However, I don’t see any direct relationship here, which is the point that the Fed is testing; they are trying to see if “absorbing” so many reserves, and $402 billion in the last test week is not trivial or insignificant, leads to disruption in liquidity. Since liquidity has been relatively calm since October 15 there is nothing to lead to suspicion that TDF has had any real impact whatsoever in that direction.

In fact, my own thoughts here are very much like those of the reverse repo program. This all sounds nice in theory but I highly doubt it will be effective in practice for exactly the same reasons the RRP failed so spectacularly – Fed-based liquidity is not a good substitute for freely flowing private liquidity as incentives and considerations are completely different (not to mention the former being bureaucratically rigid).

That leaves implications about how serious the Fed is in terms of ending ZIRP, which is what the author quoted at the outset was perhaps suggesting in his highly misleading and erroneous way. Firstly, when this latest test ends next week total bank reserves are going to rise by $402 billion (unless the test is extended, but I haven’t seen any indication of that), which will completely erase his whole “bond dumping” theory outright.

The more plausible interpretation toward the Fed’s intentions of ending ZIRP are the size and scope of the recent tests; are they ramping up in anticipation of close rate hikes? That may be true, but the RRP underwent similar testing including an enlarging scale over a year ago, and has remained in effect (ineffective) the entire time. It may be that the TDF means the Fed is more serious, but I don’t think it is straight inference like that at all. I rather believe, as the October FOMC minutes suggested, that the scale of the TDF is related to the failure of the RRP. In other words, recognizing that the RRP didn’t come even close to its design specifications, the Open Market Desk better find out quickly if the TDF can take up the chore.

That’s the problem with these tests as they don’t necessarily tell the Fed (or us) anything useful about applications under actual conditions. The RRP appeared to do what they said until the slightest elevation in stress showed it was totally ineffective. That is ultimately why I think the TDF will be as well, since the June test occurred already during duress and it didn’t appear to have any intended effects. If they were aiming to use the TDF to enforce a harder interbank rate floor, it did nothing toward establishing one, failing right alongside the RRP (as repo fails show, repo rates were not responding to any “floor” at all but rather staying significantly negative). In that respect, if the TDF test in July was “real”, and it topped out at $153 billion, there isn’t much hope for success there either.

The problem here is confusion not just in accounting but in theory. It seems as if conventional wisdom still sees “reserves” as a perfect substitute for liquidity – yet that is the very problem the Fed is trying to solve with its “absorption” tests. As I showed in basic interbank math, liquidity is not a quantity of dollar bills, Federal Reserve Notes, sitting in a vault somewhere to be dispersed by Brinks truck, nor is it even a ledger balance liability connected with the word “reserves.” Liquidity is a private affair far more remote from the central bank than anyone seems to realize. In other words, the Fed acts (tries) out of influence rather than direct intervention. There are far more relevant variables than bank reserves to systemic liquidity, and further to credit production which is why all this math disproves anyone who tries to connect QE’s end with either “inflation fears” or oil prices.

Reserves, as I restated before from the Fed itself, are nothing more than a byproduct of monetary policy. There is no sense or benefit in reading too much into them.

Stay In Touch