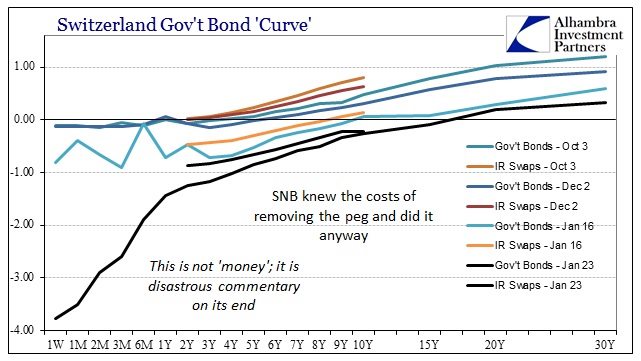

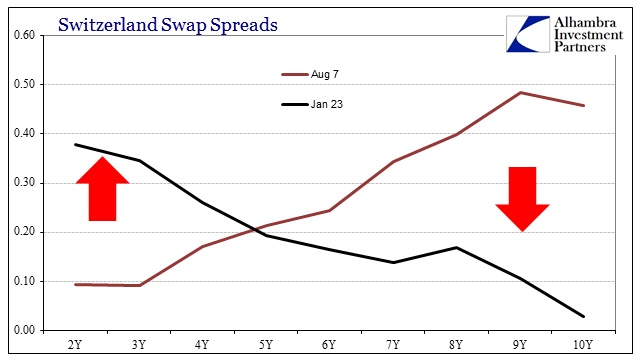

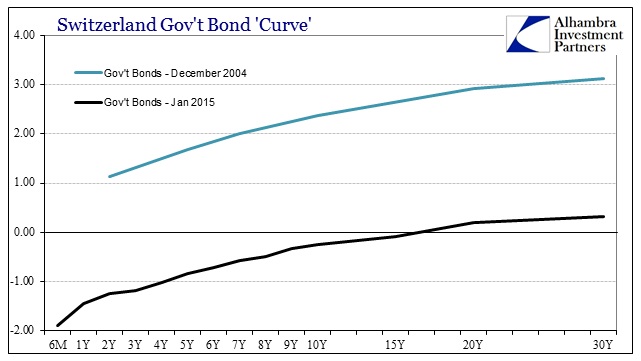

Recognizing the danger of being understated, Swiss markets are a disaster. The overnight rate at -4% handily beats out the periodic specialness in US$ repo which settles at the penalty rate of “only” -3%. The 10-year bond rate is -.257%; the 15-year at -.083%. The Swiss stock index fell more than 14% in the two days after January 14, and remains almost 12% lower. None of this is surprising given the circumstances.

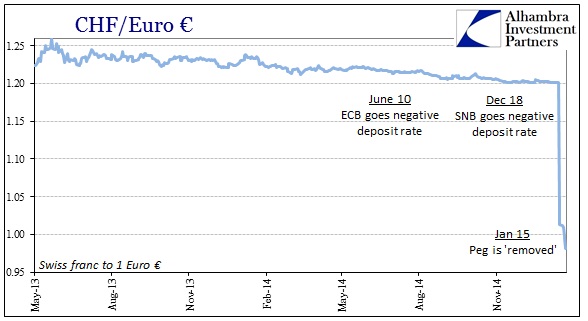

In other words, the Swiss National Bank knew what it was getting into when it removed the peg. It remains to be seen how much of this disorder relates to the upcoming Greek election, and how much is more structural in the context of deep, deep problems in broader Europe. However, the settling “wisdom” about the SNB’s move doesn’t make much sense to me.

With more than a week to digest all the disruption, mainstream commentary seems to be relating the peg’s disintegration to the potential size of SNB intervention had it not done so. In other words, the peg required the SNB to intervene to defend it, especially since October, leaving the balance sheet at the central bank dangerously swollen.

The SNB lost some money by leaving the peg on its 40% of Euro-denominated assets. But it could have lost a lot more if it had kept their peg and were forced to buy even more assets. Had it kept the peg, SNB assets would have likely grown over GDP quickly after the expected QE announcement, and losses due to FX volatility could have potentially impacted the sovereign.

There is no doubt that this was a consideration, but I find it lacking as the primary reason for abandoning the Swiss “defense.” The balance sheet was already highly out of alignment with other central banks prior to even January, and the Swiss have made it known, very plainly, they don’t actually care about “losses” as they consider that to be a matter for private banks not central banks.

All that, however, is nothing but “ifs” and “mights”, future potential problems should conditions surpass some unknown threshold. Undoubtedly, defending the peg would have been more than uncomfortable, but the SNB has been in this position before, notably when they instituted the peg in the first place. That’s asking and courting a lot of massive and negative financial feedback upon an unknown probability; no matter how much ECB QE might have upped it.

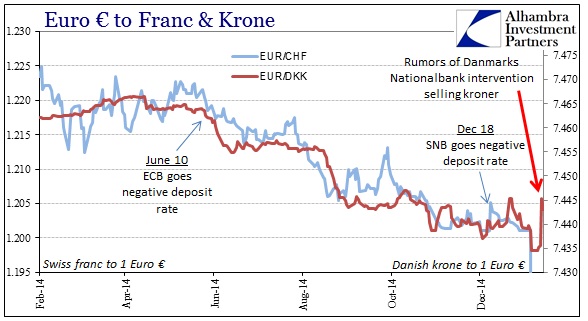

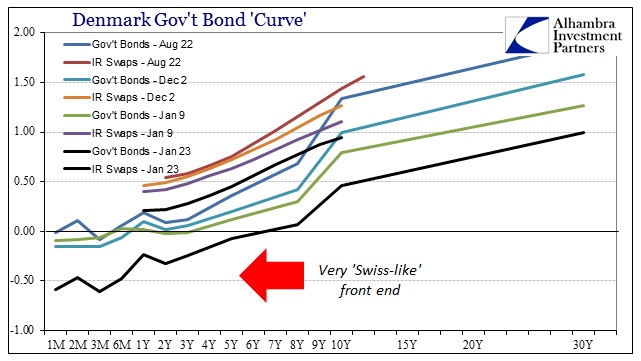

I often compare the Swiss “markets” with those in Denmark because there are many similarities of construction and relations to wider Europe (though not size and depth). In that respect, even considering disparities, the behavior of each respective central bank in the past ten days is, I believe, very informative about why the Swiss acted the way they did. In short, the Danmarks Nationalbank has done a complete opposite to the SNB. While the Krone has come under the same kind of buying pressure as the franc, it has remained very well-behaved, relatively, and still within the soft “peg” set by the Danmarks Nationalbank.

“We have plenty of kroner,” Karsten Biltoft, head of communications at the central bank in Copenhagen, said in a phone interview. “We have the necessary tools in terms of interest-rate changes and interventions and we have a sufficient supply of Danish kroner.”

That comment follows further negativization of Danish money market rates and even rumors of direct kroner selling from the central bank itself. The Danes and the Swiss have taken opposite stances because, in my analysis, the Danish banking system does not have a “dollar” problem whereas the Swiss banking system most certainly does. Because of that, the Danmarks Nationalbank can “afford” to keep the kroner pegged to the euro as that is their only major financial consideration; the Swiss cannot because their banks are going to sink further as the euro sinks further against the “dollar.”

The “dollar” problem in Switzerland is immediate, thus would take precedence far and above any future thoughts and “ifs” about the SNB’s balance sheet size and allocations. That the SNB would look upon the expected (and now confirmed) damage to Swiss money markets and elsewhere and conclude the cost/benefits weighed in favor of acting on the “dollar” rather than keeping to the euro (and long the European recovery) suggests a heavy element of desperation about how far this “dollar” problem just may be going. Again, I don’t think the SNB ignored the potential for difficulties in a swelling balance sheet situation, but that was just one more factor to weigh against not acting on the “dollar” imbalance.

Stay In Touch