The amount of inconsistency is certainly consistent when viewing the trouble mainstream analysis has with trying to exclude the possibility of economic forces from explaining why things are the way they are. The latest trade data from China was deafening, too much to pass off as a simple case of a minor blip. Exports in January declined rather sharply, “unexpectedly” of course, while imports simply collapsed:

Exports dropped 3.3 percent from a year earlier, against a median expectation of a 6.3 percent gain, while imports plummeted 19.9 percent, the biggest slide since May 2009, a time when the economy was dealing with the global recession.

The reason economists expected a pretty good gain in exports:

Thinking that easing measures in Europe would boost demand for Chinese goods, analysts polled by Reuters had expected to exports to rise by 6.3 percent, and imports to fall by only 3 percent, to give a trade deficit of $48.9 billion.

Again, self-reinforcing bias over the efficacy of monetary policy that continues to at least stumble, if not make the whole condition that much worse. However, the “shocking” part of the equation seems to be the import figure, not because it is to such a greater magnitude but because it seems far easier to ignore or pawn off as solely a currency problem. The price of oil has declined so much it skews the direct interpretation of volume, so most of the optimistic economists can talk instead about the “dollar” rather than the fact they were so far off on Chinese exports too.

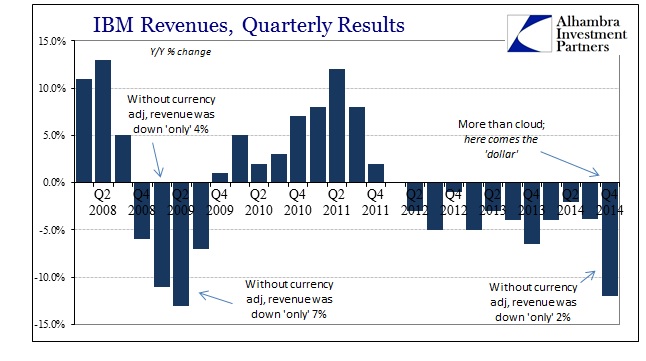

But the fact that the relevant comparison for January 2015 in terms of Chinese imports relates only to May 2009 and earlier makes this “dollar” appeal moot. Lest anyone forget, the only time we have seen a greater collapse in oil prices just happened to be at that moment; so in May 2009 Chinese imports were also within the “throes” of a “dollar” issue. It should not be this difficult to connect the dots between “dollar” problems, global recession and “unexpected” trade difficulties – they are all part of the same process. Thus, the combined appearance of all three is not at all “unexpected.” This is the trade “sister” of corporate America’s “dollar” loathing of recent vintage.

We know this is not just a crude oil problem in China because shipping rates have collapsed along with trade. The Baltic Dry Index itself is made up of three “rate route” components, each showing massive declines when compared to even the Polar Vortex of Winter 2014. The BCI Cape Index is down 24.2% Y/Y to a spot price of $6,719; the BPI Panamax (largely shipping to and from the Asia, including the Pacific round voyage) is down 66.7% Y/Y to a spot price of $3,466; and BSI Supramax is down 43.6% Y/Y to a spot price of $5,473.

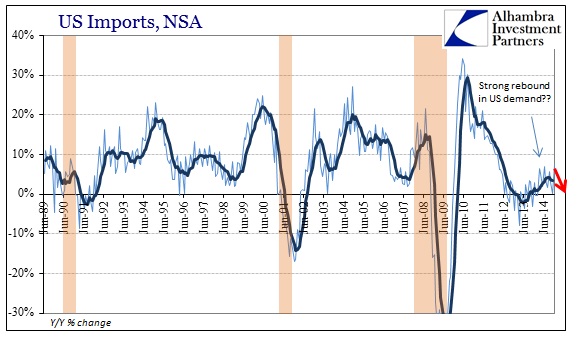

The world simply has an ongoing “demand” problem as the global economy just never fully recovered from the Great Recession. I have used the data from the US Census Bureau on import activity into the United States to demonstrate that.

The lack of US demand for physical quantities of global goods (which is practically the textbook definition of “demand”, only clouded by the Keynesian/monetarist tradition of jiggering the currency) has created all these downstream economic problems of severe consequences. The fact that Europe has been similarly stumped and locked into the euro’s noose only amplifies the persisting global carnage. Since late 2011, central banks have been trying to “stimulate” and reflate almost everywhere but all that has moved in that direction has been asset prices into dispersed, gigantic bubbles.

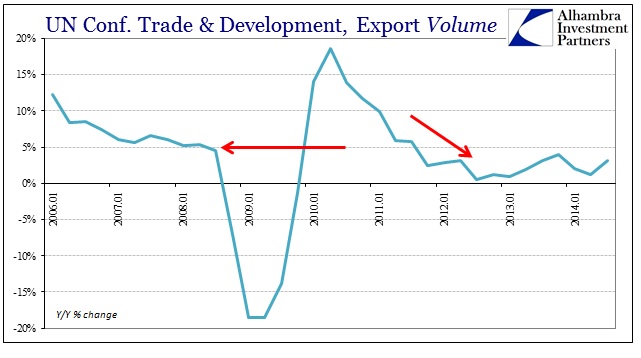

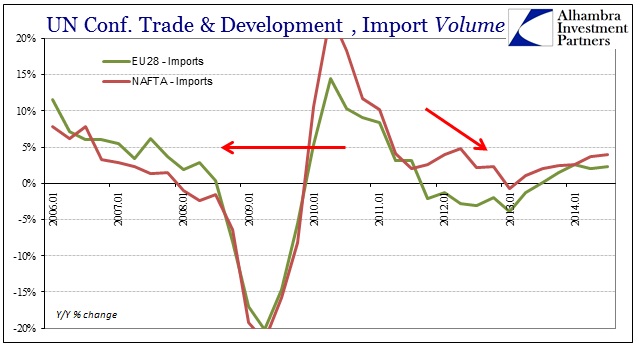

While the US import data includes the “dollar” effect, as it has to by definition, the UN Conference on Trade & Development provides a volume index for global trade (the index starts in 2005, and the latest update is Q3 2014). As you would expect, the pattern for total trade volume follows closely even the dollar value of US imports shown above.

Global trade falls off dramatically into 2012, bottoms somewhere around early 2013 (the “first” ultra-snowy winter), and only slightly recovers into 2014 – all the while remaining below trade growth rates that started this deficiency after the US housing bust took shape in 2007 and 2008. On the “demand” side, import volumes into Europe and NAFTA regions show quite clearly why global exports remain depressed.

The Chinese are “unexpectedly” struggling in economic terms simply because their customers have never recovered from the Great Recession. The PBOC attempted to fill the gap between these slowdowns and the expected recoveries, but as we enter 2015 it is increasingly clear that not only will those expected growth periods never arrive the expiration date on “extend and pretend” has drawn nigh. There is no Chinese recession or Brazilian recession in and of themselves, there is only global economic disaster to which the world’s central banks are both powerless to counteract and to blame for them (yes, the “dollar”).

Stay In Touch