I know too well that the current thinking on the economy and labor is that any activity is “good” activity, and thus better something happens than resources remain idle. I think that notion is easily disproved by common sense, as waste is not just “wrong” but harmful over the longer run. But economics is impervious to anything related to the calendar, owing so to Keynes himself, so all that matters is what happens tomorrow rather than how what happens tomorrow affects what happens next year (or five years from now).

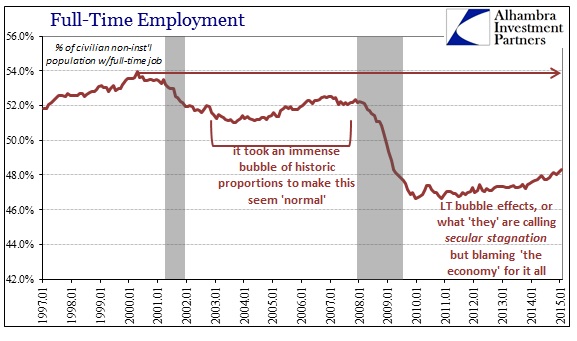

My sense of problems in the economy relate to “demand” more than anything because of this narrowness in not just scholarship but in dramatic interventions based upon these assumptions. The establishment of the economic narrative is predicated on the Establishment Survey and the unemployment rate, but yet downstream indications that should be in agreement are decidedly not. So happily married to trend cycle analysis are economists that they haven’t even noticed their other half has strayed to a new mistress, economic reality.

Count me among those that see not just a statistical “science” evolving from description and observation to influencing and yes pandering; haranguing from the BLS at the upper extremes of highly volatile but ephemerally “solid” math. However, focusing too much inside the math courts danger of being thought nothing but a crank and crackpot no matter how inconsistent and debased the justified ire. The Establishment Survey is a sacred cow and likely to remain as much to the last when everything will suddenly become “unexpected” yet again.

But nothing has erased the activity “problem.” Setting aside all questions of propriety about the payroll estimates, there is still the rather major deficiency in all features of “demand.” The global economy suffers (perpetually post-crisis) from a distinct lack of it, which causes all sorts of problems for something that solely counts the number of payrolls (and not even that, but the variation of payroll changes around some statistically estimated benchmark; but I digress again). Even if we assume that the count of payrolls is correct, that has not solved the “demand” problem yet after seven years of constant “stimulus.”

It is not outside the realm of experience that the entire marginal array of consumer and household preferences may have been altered lastingly by related events. There is, of course, historical experience in just this kind of “mystery.” The 1930’s was replete with permanent alterations to prior economic assumptions, as the reality of the deficiencies of that era caused actual changes in behavior – including financial behavior.

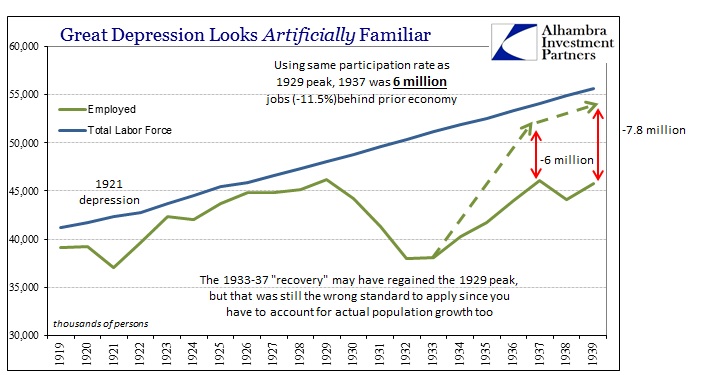

There can be no doubt that a full part of that altered “reality” related to the track of the “recovery”, or reflation more specifically. Just like the past five years, everything was moving in the “right” direction but “somehow” never really regaining prior levels of resource engagement. As much as the count of payrolls expanded, it was never enough to redeploy everyone that had been run over by the crash and collapse. That was the dominant feature, as so many that had lost never really regained – something that a huge chunk of the current labor market has had too close association.

But what is equally interesting is that the conventional narrative about the end of the Great Depression is so close in description to the questions about the current “end” of the Great Recession/lack of recovery cycle. If we again set aside statistical validity of the Establishment Survey and just assume those jobs are “real”, then the last few years look very much like the last years of the Great Depression.

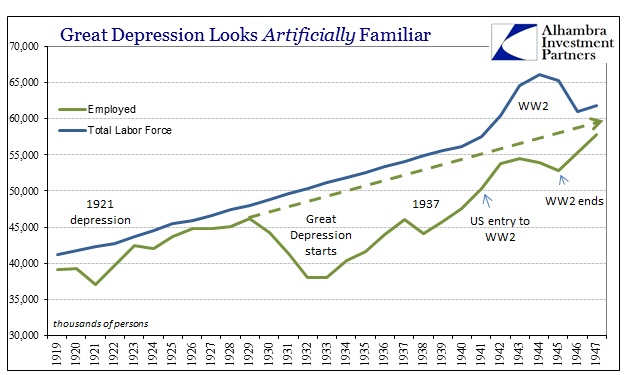

The orthodox treatment about full recovery was that World War II ended the disaster (from one to the next, a simple fact that seems to elude this fantasy). In terms of raw employment, that just wasn’t true.

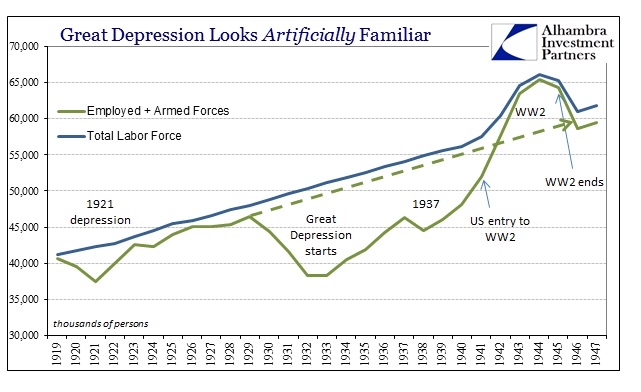

At most, the beginning years of WW2, in the buildup phase, only got total employment levels back closer to where they were on the eve of the great collapse. In fact, the latter years of WW2 saw a lower level of employment almost equivalent to its start. What changes the “look” of the 1940’s, in economic terms, is nothing short of full conscription.

If you add in the armed forces, which is taken into account in the unemployment rate, as it should, the levels of unemployment were record lows; looking very much like a full revival. But that vast expansion of the military, by necessity, did nothing much for the economy as all that potential labor was caught up in actively destroying almost in total much of two continents (and pieces of others). Even as far as domestic activity, the presence of wages meant little toward progress since so much of domestic demand was bottled up by shortages and rationing.

As far as marginal circulation, everything ran through the government as the pile of “unused” wages instead flowed to government bonds (either directly in war bonds, or as bank savings used not for private credit expansion but the purchase of the same). These things hardly count for economic expansion other than the Keynesian definition of doing something for the sake of doing something. In other words, people had jobs and incomes but were still relatively poor as the war did not create anything like broad prosperity.

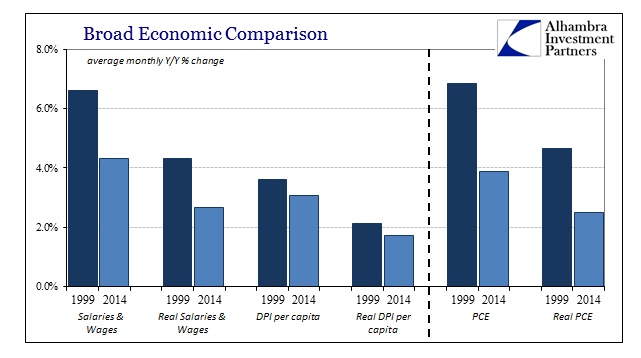

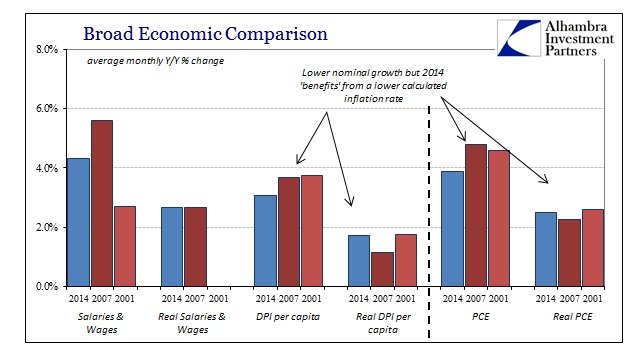

That sounds far too familiar to be comfortable about the current economy. In short, there is too much redistribution echoing of the later Great Depression in what we see now of labor utilization and especially wealth creation and prosperity. World War II was a tremendous waste of resources (this is not a political commentary about its necessity, only the economic terms of its existence) that only appeared to end the global depression. In that manner, activity for the sake of activity should be taken under the same set of assumptions and interpretations. It would at least offer an explanation as to why the greatest jobs market since 1999 doesn’t act like it in any way; instead remaining more like the pre-recession year of 2007 or the fully recession year of 2001.

It is simply not enough for labor to just be “doing something” as eventually that waste is revealed as harmful toward sustainability over the longer-term. The only way a sustainable recovery happens is for organic and profitable opportunities to be taken by economic agents free of monetary intrusions. The global death of “money”, like the later 1930’s and early 1940’s, simply does not help to our shared economic goal.

Stay In Touch