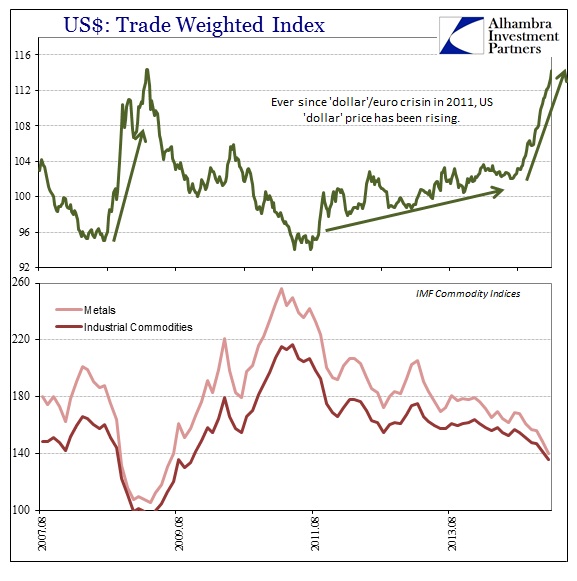

To many, the “strong dollar” will always be an economic condition. If the price of the dollar is rising, then it will be assumed, mostly by economists, to be a relative judgment in favor of domestic growth potential and reality. That view misses the very relevant fact that “dollars” are not necessarily of domestic origin or for domestic purposes. The eurodollar standard ensures that “money supply” is tied very closely to overseas financial factors, which include perceptions about the US’ place in the global economy.

So it may seem tautological to compare commodity prices denominated in “dollars” with the “dollar” itself. However, these are actually different systemic factors combining to intertwine financial function with economic function.

It would make sense in the eurodollar view for the “dollar” to be rising ever since the near-panic in 2011. That event was by and large an permanent or at least durable impairment of global banking that has not been unwound by the dramatic implementation of monetary programs. Rather, central bank activities sought instead to incorporate private “funding” functions onto themselves; without actually resolving disabilities in the global system.

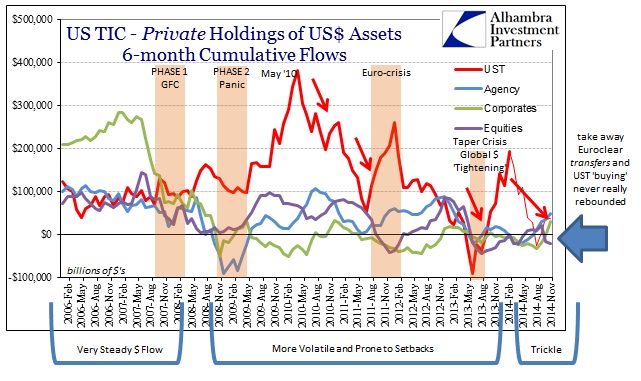

In terms of raw eurodollar mechanics, European banks have been withdrawing leaving little to fill the gap. Thus there has been a vast difference between “money supply”, as what people believe central banks do, and actual monetary fulfillment which is most often a derivative function of various and purely financial factors. In other words, what counts are not public balance sheets creating “reserves” as an exclusive byproduct of “emergency” intrusions, but the far more important monetary “flow” of private procedures.

If the “dollar” is rising, it means banks are participating less, in the aggregate, in fruitful “flow” across the global economy. Banks withdrawing, in the aggregate, balance sheet “supply” will likely come as a result of perceptions of future difficulties rather than the “strong dollar” view that believes the opposite. In that respect, it makes sense beyond the tautology where a rising “dollar” price indicates financial perceptions of weakness, diminishing “dollar” supply, in full accordance with, and related to, commodity prices that must physically clear supply and demand at lower and lower levels.

Again, as I have said before, the truly strong dollar regime is not even possible under the current global financial framework. An actual strong dollar was one that maintained convertibility and had absolutely nothing to do with its “price.” The current air of the “rising dollar” is just another instance of further instability, which is undoubtedly a factor in continued economic attrition – in direct contradiction to what central banks have everyone believe is happening.

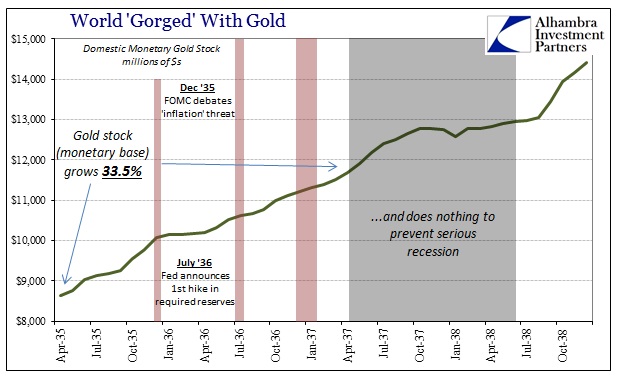

This is not unique, as even in the middle 1930’s this kind of “flow” problem was paramount. Unfortunately, owing largely to the Chicago school and Milton Friedman, monetarism instead viewed “money supply” as the only factor to consider even though it was clear by the 1937 depression-within-a-depression that such was no guard against severe economic retrenchment. The United States was, in the contemporary words of the BIS, “gorged with gold”, but 1937 happened anyway as “flow” was impaired by persistent uncertainty and then flat out policy stupidity and misinterpretation.

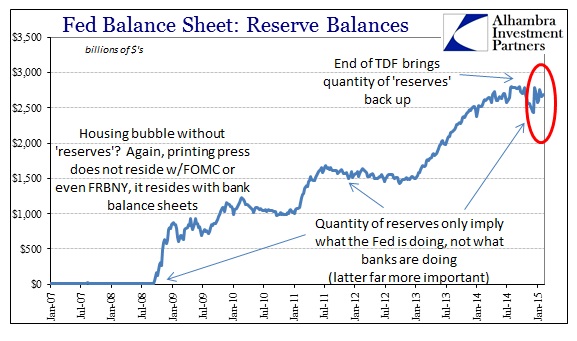

The same kind of view is available in the 2010’s by looking at bank “reserves” so amplified by all the QE’s and “extraordinary” programs of the post-crisis era. The “price” of the “dollar”, as does inflation, bears absolutely no resemblance to the quantity of bank “reserves” because in fact, not theory, bank “reserves” are not the primary monetary factor (or even a relatively important one).

That is to say that central banks have far less control than most people think, and even in regard to what they think, as they cannot conjure much of anything let alone a full recovery. If that wasn’t clear enough in the full spectrum of data, it is at least so in the years since 2011 when global central banking went “all in” on orthodox monetarism and got the opposite effect as intended in almost every case (except, of course, stock prices).

The difference between the 2010’s and the 2000’s is exactly that – bank balance sheets were unaltered in the housing bubble era (that really began in 1995) and could thus perform this monetary transformation (that, as you see directly above, required no expansion of bank “reserves” to take place) without impediment; which was precisely the problem leading to massive and dangerous imbalances without any actual restrictions placed on the process. After 2011, there is no more transformation except what can be proffered of asset prices (such as European PIIGS debt or US stocks).

Stay In Touch