I sincerely look forward to the day, which I believe wholeheartedly will come, when scant attention is paid to whatever monetary officials make for official statements about official positions. The times being what they are, however, demand inconsistency be answered. That is especially true wherever the FOMC has taken not just to being the “lender of last resort” as supposedly designed in 1913, but rather “market of last resort” in order to keep the whole of the system from once more trying to establish actual discipline.

The primary attempt at maintaining such an imbalanced status quo is the “recovery.” An actual and sustained period of true economic growth would cover a lot of problems, which is why so many Keynesians long so fondly for the 1950’s that “paid” off the huge debts of the 1930’s and 1940’s. That was always the plan even from the ashes of the panic, as “extend and pretend” was the proffered “solution” not to the recovery itself but rather bridging the divide between heavy recession and its natural and organic appearance.

Unfortunately, seven years can no longer be called a “bridge”, as extending so long amounts to admissions of fecklessness. So QE was changed in the public mind from restoring “normalcy” (market of last resort; backward redistribution) to an economic management tool via inflation expectations (forward redistribution).

Therefore the crash in oil prices since June has visited upon orthodox economists no shortage of discomfort; to which they outwardly assured everyone that it was all actually quite positive for the economy. So this month’s FOMC statement contains more, between the lines, than the standard admission for completely switching interpretations:

Several participants noted that there were signs of layoffs in the oil and gas industries, and that persistently low energy prices might prompt a larger retrenchment of employment in these industries. In addition, it was observed that if capital investment in energy-producing industries slowed significantly, it could damp the overall expansion of economic activity for a period, especially if the slowing took place after most of the positive effects of lower energy prices on growth in household spending had occurred.

Most attention thus far has been paid to the first of those sentences, and little paid to that last clause, “especially if the slowing took place after most of the positive effects of lower energy prices on growth in household spending had occurred.” After?

To this point, there has been no discernable positive impact from lower oil prices. Whether from private sources like Gallup or the last few retail sales reports, spending has fallen not gained despite this “windfall” from oil. In fact, even stock analysts have started to wonder if retailers might suffer (SUFFER) from being “over-exposed” to places most directly impacted by the energy sector – no positive offsets from the rest of the consumer economy apparently.

A quarter of Wal-Mart’s U.S. stores are located in the nine oil-reliant states explored by Nomura, as well as a quarter of Ross Stores.

Piper Jaffray analyst Neely Tamminga lowered her “overweight” rating on Ross Stores shares to a “neutral” call “in view of what we believe may be increasingly negative data points around oil-driven economies—namely Texas.” Fifteen percent of the off-price retailer’s stores are in the Lone Star State. Plano, Texas-based department store J.C. Penney is only slightly less concentrated, with 22 percent of its locations in these regions.

A fifth of Target’s stores are located in areas dependent on the oil economy and 18 percent of off-mall department store Kohl’s locations. Sixteen percent of TJX Cos. and Macy’s stores are in areas overexposed to oil economies, with a similar store-base concentration for higher-end department store Nordstrom.

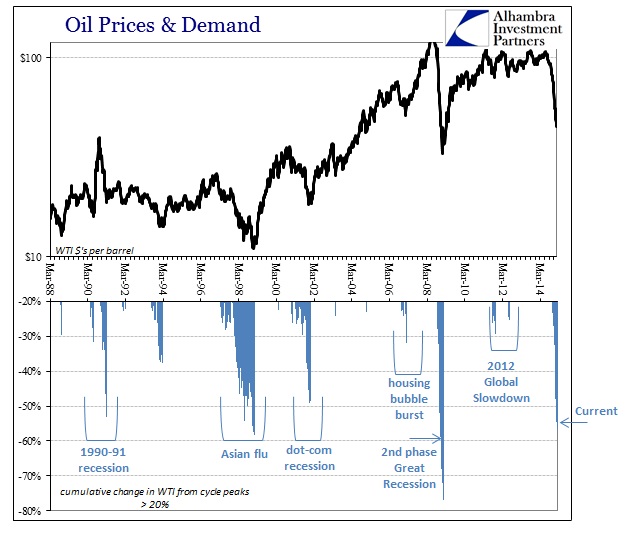

Perhaps next month the FOMC’s consternation will further evolve and openly wonder “if” lower oil prices will have any positive effect whatsoever. That is the actual world in which we live, as ceteris paribus is strictly an academic tool. In a complex economy, if oil prices are collapsing as much as they have, there are much larger concerns that come with such a price shock than to expect lower prices not be overwhelmed by them (there’s a reason huge declines in oil prices are limited to period of great economic disquiet, exclusively).

Some of this may be planned, however, on the part of the FOMC. I have said for some time that I don’t believe they would ever get to ending ZIRP, for various reasons, but were forced by their own rational expectations regime into bluffing about it (to back off threatening ZIRP would be an admission that the economy isn’t so great after all). I have to wonder if this isn’t the first step in that process, where such certainty about the economy is drained (due to foreign problems, of course) slowly as “data dependent.”

Nonetheless, a number of participants suggested that they would need to see further improvement in labor market conditions and data pointing to continued growth in real activity at a pace sufficient to support additional labor market gains before beginning policy normalization. Many participants indicated that such economic conditions would help bolster their confidence in the likelihood of inflation moving toward the Committee’s 2 percent objective after the transitory effects of lower energy prices and other factors dissipate.

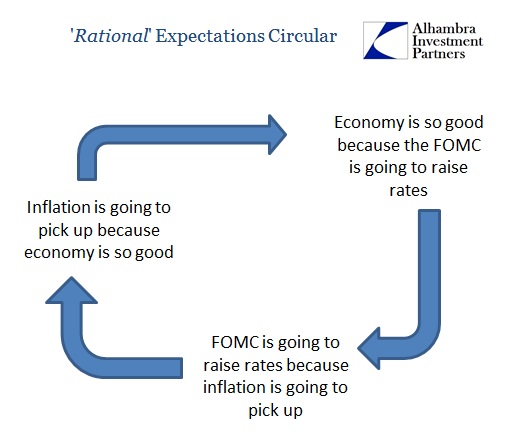

They have been saying the exact same thing for two years now, which is quite curious because very publicly it has been those same “labor market gains” that have supposedly been setting this course toward rate “normalization.” So we are left, once more, with the circular logic of the FOMC wanting to see more labor market gains before raising rates because they have seen labor market gains to convince them to raise rates.

That is the only way to consistently hold the position where “labor market gains” have been terrific but that they haven’t done much of any good toward broad economic expansion. At that point, you have to wonder what “labor market gains” actually means, other than an unemployment rate driven by people refusing to enter the labor force (aside from statistical discontinuity) during the most robust payroll expansion since 1999. In other words, they are very much perplexed that “labor market gains” aren’t actual wage gains, which undercuts the very reliance on “labor market gains” in the first place.

In any event, there is a world of difference in how the minutes of January’s meeting are being received in contrast to how the blander statement was of the very same meeting. If that doesn’t argue for banishment of all this foolishness from the public discourse then nothing ever will.

Stay In Touch