The Great Recession was seven years ago so it might seem appropriate that our memories of the specific nature and order of events is lost to time. However, given that it will be a seminal event in history (hopefully not surpassed) there is less leeway to having such a short grasp on the important pieces. Part of that relates to trauma, financially speaking, whereby the economy is conflated with the “market” (either credit or stocks) in something like realtime. When the market crashed in October 2008, though, there was still debate on the economy even at that late moment.

On September 22, 2008, the October 2008 futures price for WTI surged by $25 per barrel, a record move, hitting a high of $130 intraday on nothing more than news of TARP’s introduction into Congress. This was one week after Lehman Brothers had failed, AIG introduced the world to “liquidity” and collateral in writing CDS (and JP Morgan’s central place in them) and various other big banks were on the precipice of total disaster. And despite all of that, oil prices in that intraday moment were only a dozen dollars or so below the July 2008 all-time peak.

Investors were concerned about “demand” but only slightly so as it related to, even by Lehman’s bankruptcy, still just a “slowdown.”

“The biggest news is that people are looking at the $700 billion plan as supportive of demand, supportive of the economy,” said Beutel. “Everything we are looking at right now says demand has a chance to come back if the economy starts to strengthen.”

Oil prices had been trending lower on worries that demand was faltering but those concerns seem to be abating, according to one analyst.

“The fear has waned as far as the demand destruction” in the wake of the bailout news, said Neal Dingmann, senior energy analyst at Dahlman Rose. “The bailout has really stabilized this market.”

Again, those comments were made in late September 2008, only a week away from unrelenting and outright panic (of banks, by banks). People, investors especially, just don’t want to believe nowadays in the worst case or even a bad case. If economists say that the economy is getting better or at least there was very little downside to the real economy, as they did throughout 2008, then that message is taken at face value regardless of all contrary logic and plain common sense.

In Time Magazine, an outfit not particularly known for sharp economic commentary but representative of the mainstream public stream of consciousness about such things, as late as November 2008 they were talking about the in-motion collapse in oil prices as a purely financial matter:

Clearly, demand for oil didn’t fall that much, but the price of oil isn’t set by demand alone. It’s the product of an extremely volatile mixture of speculation, oil production, weather, government policies, the global economy, the number of miles the average American is driving in any given week and so on. But the daily price is actually set — or discovered, in economic parlance — on the futures exchange…

Translation: the banks were long on oil and probably helped effect high oil prices. But with these banks failing, and prices already declining, they too closed out those long positions and helped bring prices lower. Oil prices may have risen on panic, and fear may have played a role in their recent fall. The mechanism of the fall, however, was a massive liquidation. [emphasis added]

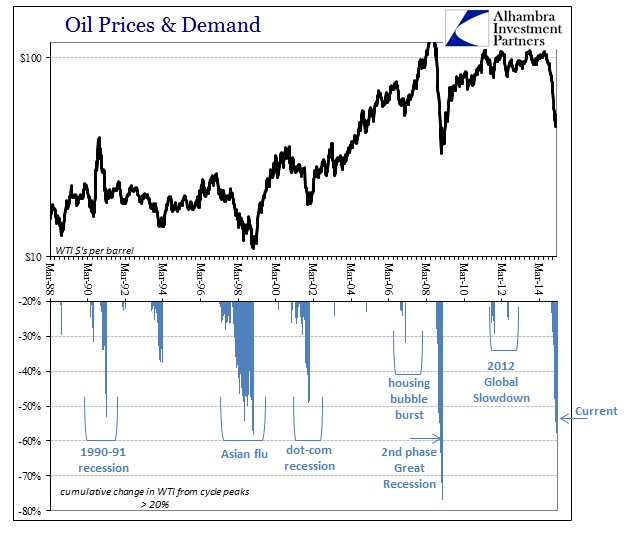

In review of that period, actually demand for oil did fall that much and not just in the US but everywhere in the world. The liquidations in oil, as in stocks and credit, were just the signals of that as bank balance sheets contracted (for “dollars”, as the global “dollar” short grew desperate). The rise of the “dollar” was merely the expression of imbalance of finance in the face of drastically shortening economic fundamentals. It was fashionable to blame “speculators” for all of it, but that was just a symptom again of how far imbalances had gained.

That put the nearly 80% drop in the price of oil in perspective, as the financial imbalance driven by “speculation” was wholly misplaced as the state of the real economy was obscured by what amounted to nothing but monetary faith. Yet, that was pervasive enough for commentary, during the worst economic quarter since the 1930’s, to continue to only “worry” about just the possibility of recession. Below is from CNN, also in late-November 2008:

Goldman Sachs said Thursday that it expects oil prices to top $107 a barrel by the end of 2009. That’s a step back from its late July outlook, which called for prices to top $149 a barrel by the end of this year.

Concern about demand for petroleum products has driven crude oil prices down from a record high of $147.27 a barrel in mid-July. The decline has also driven down the price of unleaded gasoline by over a half since July to $2.02 a gallon, motorist group AAA reported Thursday.

However, Goldman also said Thursday that it would not offer any more guidance for oil prices for the remainder of 2008, citing rapidly changing economic conditions. That might provide some near-term support.

It wouldn’t be until March 2011 that WTI managed back above the $100 mark, and there was ZIRP, one completed QE and another almost finished “to get there.” Even when the economy simply collapsed there was a total rush to simply not believe it, instead offering mostly convoluted and nonsensical explanations as to why the simply logical was more “impossible” than the persistent belief in economists’ projections. Recency bias only explains part of the undercount of what took place, as you have to appreciate the hold that economic projections play starting with the “best and brightest” at central banks.

So there is nothing new here in 2015 as the same set of circumstances combines, to varying degrees, for the fact that oil prices are being seen as falling for some reason other than renewed economic dislocation. The only twist has been a role reversal, whereby the US was assumed the weakened participant in 2008 and now is the “cleanest dirty shirt.” But as 2008 demonstrated, just not well enough to become convention apparently, there is no separation or “decoupling” as the global economy was the global economy. The 80% collapse in oil was entirely appropriate as “demand” collapsed pretty much anywhere and everywhere – and therefore financial liquidations were just as proper calling into question not speculators but exactly what basis they were speculating on in the first place (monetary policy is not neutral!).

The volatility of oil prices of late has been upsetting again the financial context:

Oil prices have closed higher or lower by more than 2% for 24 out of the 37 trading days this year, compared to just three days in the same period last year. For eleven consecutive trading days up to Feb. 13, oil prices closed higher or lower by more than 2%, the longest streak of this kind since the 21-day period from Dec. 4, 2008 to Jan. 5, 2009.

Once again the comparison to 2008-09 appears without any appreciation for why that might be. After all, there is the “problem” of nothing but supply, supply and more supply:

Last year’s selloff was driven by unexpectedly strong U.S. oil output coupled with the decision by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries to keep output steady, leaving the market awash in supply.

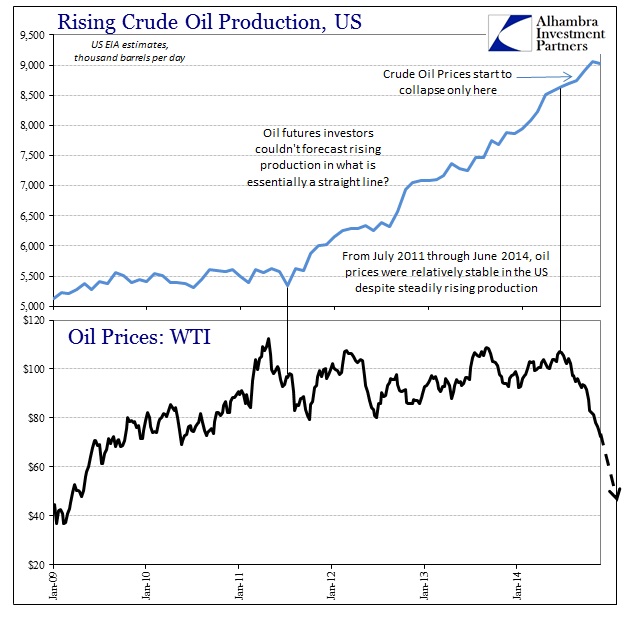

As I noted a few weeks back, it is exceedingly difficult to say that US supply has been “unexpectedly strong”, as that has been the case for almost four full years. There is nothing about supply that was unexpected, and if some factor changed so drastically as to produce a nearly 60% collapse in oil prices, and likely some new liquidations in leveraged positions, it was again bank balance sheet contracting the supply of leveraged “dollars” on less-than-robust forecasts for global “demand.” The vastly “rising” dollar and collapsing oil prices are the same powerful tendency.

Recency bias no doubt once again playing a role, but more likely it is this new-ish trend to deny any damaging economic possibility as it might disrupt the balance of financialism. Any system that cannot even countenance just a small possibility of contrary thought is not robust or “resilient” at all. As we saw in 2008-09, oil liquidations were entirely appropriate for economic conditions; how can “everyone” deny outright something even slightly similar?

Stay In Touch