Ever since the price of oil became a major economic theme last fall, even before the now-ubiquitous “dollar” though they are essentially one and the same function, economists and especially those at the FOMC have been in a rush to reassure that the oil price collapse was both going to be short-lived and a huge benefit to consumers. One didn’t have to see the obvious contradiction in those two posited outcomes (if oil prices are a benefit and they are short-lived, so is the benefit) to recognize the growing worry. Such a position from the orthodox apparatus is highly contrary to the established theory that low “inflation” is especially bad for monetary viewpoints.

In other words, the FOMC detests lower oil prices but absolutely cannot stand a full-blown collapse and thus constraint. Such a major move in oil (and the rest of commodities) also signals the opposite of what they would like to see, so their first instinct was to dismiss it as either a good problem or temporary at worst.

The only significance of this month’s “dot day” was the release of the latest “central tendency” calculations. The academic economists at the Fed run simulations through their various econometric models and come up with a statistical range about the most “likely” path. As per usual, they are consistently over-optimistic to the point that even the academics are getting nervous about how obvious such bias has become (rational expectations theory is a weird governor).

But it is especially egregious that “transitory” oil prices are no longer being treated by the FOMC as such. The foundational “dollar” problem to all of this is now being regarded exactly like one, without any such admission of the changing perspective of policymakers. Thus the stock market roars because the Fed essentially admitted that there are huge economic “headwinds” associated with oil and the “dollar” (more precisely, what oil and the “dollar” represent) despite all public protests and insisting otherwise.

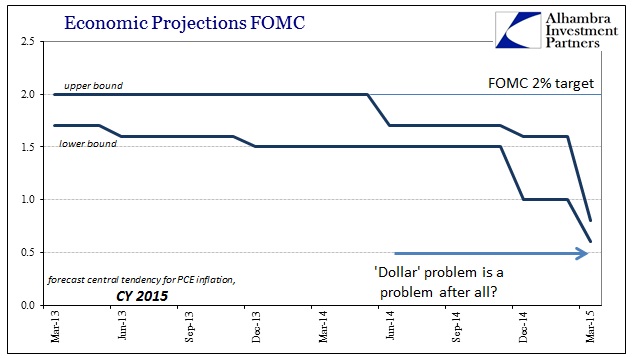

As late as last June, the Fed’s models were assuming inflation (defined as the PCE deflator) right at their 2% target. It didn’t happen all at once, as Janet Yellen at her December press conference remained defiant on oil and the “dollar”, but in the space of the last few months inflation expectations for 2015 have all but collapsed. The FOMC’s 2% target is now a pipe dream of the same persistent over-optimism bias. That would mean, in no uncertain terms, QE totally failed in its primary objective – there is no expected “inflation” let alone sustained “inflation” or GDP growth.

Reality has intruded, rudely, and stocks at least are taking it as a sign of no imminent end to ZIRP; if not already dreaming of QE5.

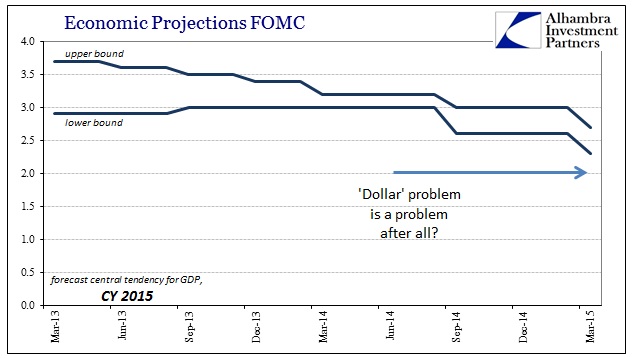

For GDP, the projected “central tendency” has been moved downward to just 2.3% at the lower bound – the same decrepit rate as the just-completed (though not yet fully revised) CY 2014. The assumed and unassailable recovery is apparently yet again not yet arrived (for the fifth year in a row).

Worse, however, is that this is only March and there are only a few months of data in hand, and only January for some accounts. In other words, the risks of over-optimism remain high despite the tantamount admission that the FOMC got it all wrong once more. While they will try to cover it up by saying that 2.3% to 2.7% is about the long-term average, that is skewed by the fact that the long-term average includes recessions. That would mean the US economy, despite all the dirty talk about dirty shirts elsewhere, remains, at best, stuck in the same deficient recovery despite four QE’s and more than six years of the zero lower bound.

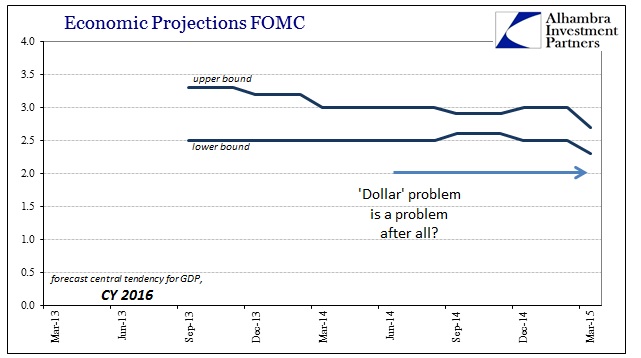

The only difference, and it is a big one as the “central tendency” calculations for next year show, is that downside risks have already appeared, have already affected much, and are not anywhere close to running their ultimate course.

It’s hardly the envisioned obituary for the “booming” economy of the unemployment rate, especially since economists couldn’t talk enough about how 5% GDP was going to be expected and normal again. Instability is instability after all, except the longer it goes the more likely the worst case “shock.”

Stay In Touch