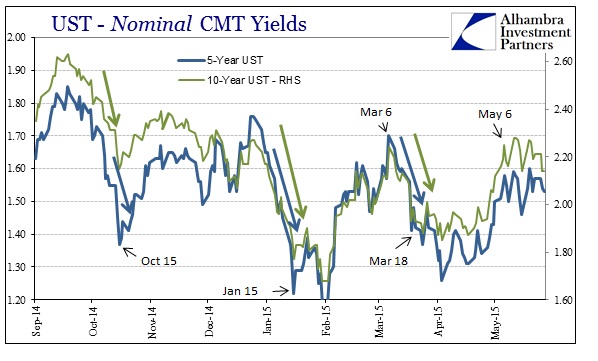

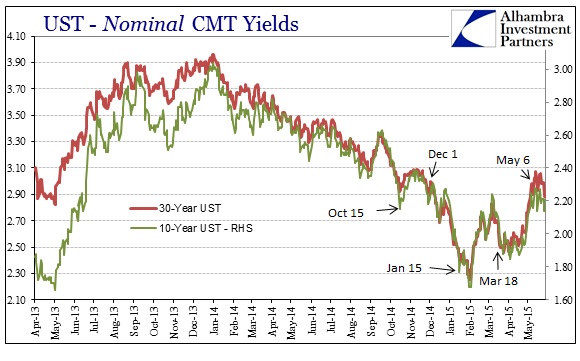

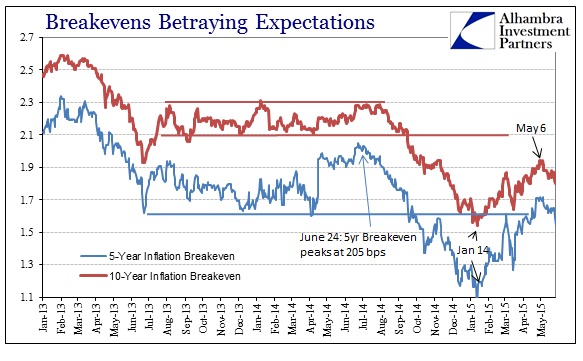

Yesterday I looked at funding markets and currency proxies for detecting the end to the “dollar” pause that began on March 18. Broader credit markets agree with that assessment so far, as nominal yields and the UST curve shape have started, at least, to be redrawn back into the tightening format. Nominal yields and inflation breakevens turned right at May 6 when Janet Yellen spoke more of the common sense that should be the default setting for monetary everything.

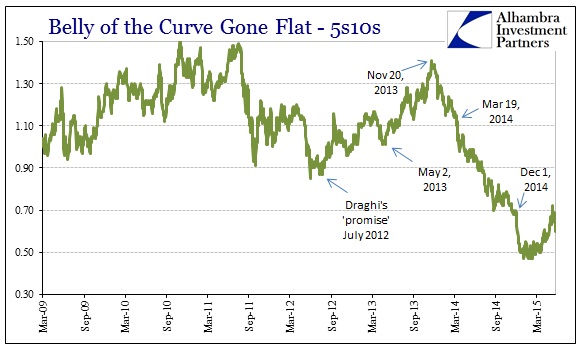

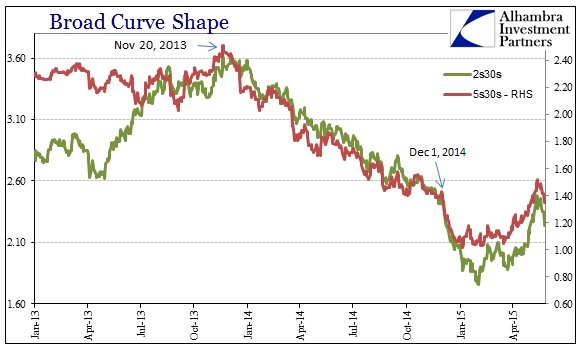

The yield curve overall across the bulk of it has moved flatter, mostly within the past two weeks. Since May 14, the 5s10s has flattened rather sharply (an appropriate oxymoron) dropping from 72 bps all the way down to 60 bps Tuesday and 61 bps yesterday. The 30-year end fell from 248 bps against the 2s down to 224 bps yesterday; from 152 bps against the 5s down to 135 bps.

As noted yesterday, it isn’t so much that these moves are especially established in order to confirm an actual inflection but rather that everything has started moving again in the opposite direction at largely the same time. That would tend to rule out random volatility in various components which was at least arguable from May 6 at first. With the entire credit and funding markets turning now together, it increases the likelihood that this is something meaningful.

And that is what makes this all the more important, as if I am using the correct interpretation credit and funding markets are all backward in relation to where orthodox narratives suggest and often demand they be. If Yellen’s speech alluding to a stock bubble on May 6 turned the “exit” to ZIRP back on, then credit and funding should be behaving in the same manner as the middle of 2013 – rising nominal yields and a steeper yield curve (eurodollars too). But that was the behavior of the period just prior to May 6, when it was quite clear that credit was taken with the belief, of March 18, that the FOMC had changed its mind away from the exit.

That has really been the persistent trend since November 2013, where the more the FOMC talks about being convinced of a full economic recovery, and thus gets closer, in their collective mind, to an exit from ZIRP, the more upside down these markets get. The only way to explain that is what I alluded to also yesterday, namely that credit and funding are finding “there will not be any normalcy and any attempt to go backward undertakes what amounts to incalculable risk of being disastrous.” In this view, “backward” applies to the idea of financial (and economic) normalcy when operative financial conditions completely prevent that:

I personally find way too much complacency in blindly believing that going from B to C will be only a minor inconvenience. It would be dangerous even under the circumstances where the system shifted from the dealers to the Fed and back to the dealers, with an infinite series of potential dangers even there. But to undertake a total and complete money market reformation from dealers to the Fed to money funds? There are no tests or history with which to suggest this is even doable under current intentions. Poszar and Mehrling’s contributions more than suggest that difficulty, but I think that still understates whether or not we ever get that far.

That, I believe, describes this upside down nature coursing through credit and funding at the moment. Whenever the Fed or its top officials (they call themselves, often, thought leaders without ever demonstrating the capacity for wide-ranging curiosity) get back to this aching, nagging fear of not confirming their past success, eight years is a long time to be in an “emergency” after all, credit markets reciprocate with their irritating fear of centrality in these paradigm shifts themselves.

You could make the case that this is one instance, spread among many facets, where “markets” are just throwing a tantrum having become used to, and dependent on, central banks. There is undoubtedly some of that at work, as certain parts of the financial markets are unduly comfortable with the way things are at this moment, but that is much more so related to the risky parts of finance than the basis here. Funding markets, in particular, are the most closely associated with the changes to come (if, once more, we ever get that far) very much aware that this all amounts to a change not just in interest rates but in the very character of operation. That is far different than just being emotional over the Fed no longer babying and nursing closely financialist components (a reception carried more much openly by stocks).

Critics of the massive interventions (including institutions like the BIS) spawned since late 2008 have maintained that eventually they produce a market system that no longer operates like a market system. We have seen that in some moments as stocks will behave contrary to how they used to, “risk off” on seemingly good news and such, all in the view of monetary policy with usurped primacy. In the case of credit and funding, I think it is actually worse than that as it is the investors and financial agents playing the role of realism, literally making for this upside down re-arrangement. That is why November 2013 looms over everything, as the financial system peered closely at what the “exit” might look like and recoiled drastically in rejection of it.

Central banks took over everything and thus changed everything; they cannot simply declare themselves successful and just give it all back. That might (stress might) have been possible had it actually worked, a true and robust economic recovery to smooth the shift, but the majority part of that November 2013 recoil was the growing acceptance, throughout 2014 and into 2015, that it was never coming in the first place.

Stay In Touch