This morning HSBC announced plans to radically downsize its cost structure, mostly through cutting jobs. Most of the attention so far has been on the bank’s plans to use the expected profit boosts to fund a period of rising dividend expansion. Immediately, as a business, there is a bit of a conflict in that attempt as typically expanding dividends and shareholder “returns” is byproduct of successful business activities. When you grow organically you can direct more cash flow to your shareholders in greater proportion. To do this through heavy cost cutting, a reduction in global headcount of 25%, is surrendering on that point.

Unfortunately, this has been all-too-common in the post-crisis era of almost every large business. The impulse to “return” cash flow to shareholders has been overwhelming but not due to a massive and robust expansion, rather almost as financial penance for its absence. For global banks, however, there is the monetary element to consider as well which makes their participation corroborative of other assessments.

HSBC starts with a purported plan to reduce its risk-weighted asset tally by 25%, or $290 billion. Those are large numbers and while they do not necessarily mean asset sales (or security sales, which usually does not occur unless the bank is highly stressed) the bank is committing to selling down its global profile. That starts, apparently, with subsidiaries in Turkey and Brazil.

Europe’s largest bank by assets also revealed plans to streamline its 260,000 strong workforce and trim its branch numbers by around 12 percent. The bank said it intended to sell its Turkish and Brazilian operations—although it will maintain a presence in Brazil to serve large clients—in what the it called a “significant reshaping of its business portfolio”…

“Brazil and Turkey have limited value to the franchise and that is why we have made the announcements we have today. These announcements prove there are no ‘sacred cows’ in the business,” HSBC chief executive Stuart Gulliver told investors on a conference call following its statement.

“Limited value” as it stands now, but that wasn’t the case when HSBC was enthusiastically embracing BRICs and emerging markets. The bank intends to continue on the path in some EM’s, however, just those in Asia rather than elsewhere. As noted by the Wall Street Journal at the end of April,

It is unclear how much of the Brazil unit, which employs 21,000 people, is up for sale, these people say. HSBC’s Latin America division, which also includes Mexico and Argentina, suffered a difficult 2014 with adjusted profit before tax dropping 50% as the Brazilian economy slowed. Meanwhile costs rose in the region, impacted by union agreed salary hikes and inflation.

HSBC runs the seventh largest bank in Brazil with a 2.7% market share, in terms of assets. HSBC Brazil swung to a loss of around £200 million ($306.8 million) in 2014.

If it was just HSBC this might all simply be the case of a bank getting far too overeager. History is littered with such examples and it is a very common risk for any business that grows and grows rapidly. But there has been a more subtle turn in global banking just this year, much broader than one big bank admitting to overenthusiasm. Just in the past few months, CEO’s at other banks have resigned while still others are redefining and even contemplating completely rewriting their strategies.

Brady Dougan, who just last year was being praised as a “survivor”, resigned in early March from Credit Suisse. He had been in the CEO position since 2007, enduring both the Panic of 2008 and the tax “scandals” and legal pressure last year. It has been noted that Dougan continued on through constant upheaval while close rivals such as UBS churned through executive after executive. He could survive allegations of wrongdoing and but he could not perform where it mattered most:

Dougan, who headed Credit Suisse’s investment bank before becoming CEO, resisted calls for a radical downsizing of the securities unit following UBS’s decision to do so. He instead focused on incremental cuts to the business and costs to improve earnings. The strategy hasn’t paid off for shareholders, with Credit Suisse shares currently trading at about 1.1 times the bank’s tangible book value, compared with 1.4 times for UBS.

Of course, earlier this week, Deutsche Bank announced the resignation of its co-CEO’s, Anshu Jain and Jürgen Fitschen. Fitschen is on trial for his alleged part in a business collapse unrelated to Deutsche Bank while Mr. Jain has been criticized from the moment he was promoted because he is not fluent in German. However, neither of those warranted dismissal or even untidiness. The shakeup is, again, much larger, amounting to, again, undesirable performance.

The sudden resignations, first reported Sunday by The Wall Street Journal, introduce the possibility of major change at Deutsche Bank. In April, Messrs. Jain and Fitschen took their latest stab at an overhaul strategy to streamline the at-times unwieldy bank and boost its profitability. But to the disappointment of some shareholders, they stopped short of a radical plan to break up Deutsche Bank’s investment-banking and retail-lending operations into separate companies.

Earlier last month, Deutsche shareholders approved of that strategic plan by only 61% in favor; that was, according to the Journal, a record-low approval.

There are other management departures around the global banking community as well as serious realignments much more quietly being implemented. Standard Charter’s CEO and the head of its Asian unit resigned in late February due to “unrest” at that global bank, traced to poor banking performance in India. The big business of big global banking does not seem so glamorous in 2015 particularly in comparison to a decade ago. These titans were everything then, and their rearrangements now, at this particular moment, are poignant.

In some ways, this is just recognition of the state of the global economy. Banks were clearly betting on “global growth” just as every economist in the world told them to, including their own. It hasn’t worked out and the pointed turn, almost as a herd, in 2015 more than suggests that even the biggest banks are giving up on the central banker narrative.

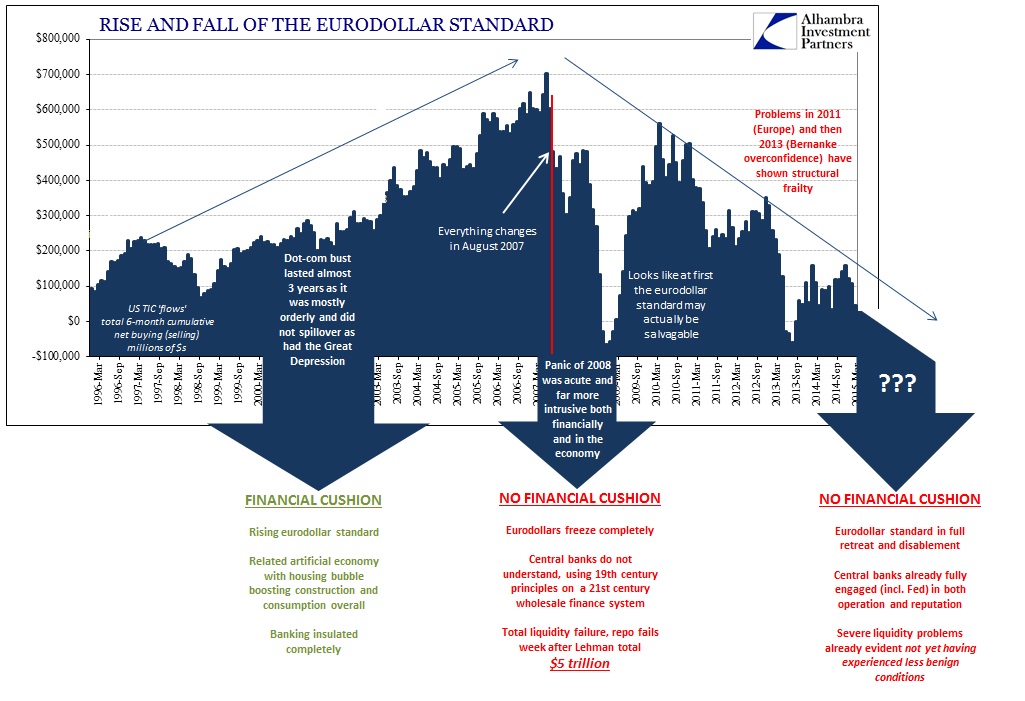

While that is certainly significant in its own right, I don’t think it offers a complete picture, either. The rise of HSBC, Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank was coincident with the eurodollar standard because they were the agents of the eurodollar standard. They rode the wave on the way up, becoming far greater than anything imagined before in both size and reach. That was a problem starting in August 2007 as that meant their “dollars” weren’t always as negotiable as they once thought, but it was in everyone’s expectations, including the Federal Reserve, that such interruption was but temporary and that their place at the global financial apex was still reserved if not permanent.

As I wrote yesterday, it is impossible to separate global finance from the global economy. That it is almost ubiquitous in 2015 for shareholders and analysts (as well as the banks themselves, if only reluctantly at this point) to call for unwinding all these “unwieldy” bank behemoths offers an almost perfect bookend to the eurodollar standard. Bigger was everything in the last decade, and now it is almost if not quite poison. These banks are examples of how the eurodollar standard arose and dominated, and I believe are now showing us directly how it is all unraveling; and even the point to which that process has progressed.

I don’t have any complaints about this as in almost every respect it is a welcome development; save one.

I personally find way too much complacency in blindly believing that going from B to C will be only a minor inconvenience. It would be dangerous even under the circumstances where the system shifted from the dealers to the Fed and back to the dealers, with an infinite series of potential dangers even there. But to undertake a total and complete money market reformation from dealers to the Fed to money funds? There are no tests or history with which to suggest this is even doable under current intentions. Poszar and Mehrling’s contributions more than suggest that difficulty, but I think that still understates whether or not we ever get that far.

Clearly the entire eurodollar system has been undertaking pains of withdrawal all the way back to August 9, 2007. What is at issue is what might constitute that second transition, to get from B to C. Poszar’s scenario is one of a relatively familiar C, with some difficulty in achieving it (largely in the Fed “holding its nose” about the RRP’s) and Mehrling (and I really don’t want to speak too much for him) looking maybe a little past that. My position is that the transition has already been rocky and with some very dangerous results so far (October 15, January 15). The Swiss National Bank can attest.

If the eurodollar system were to be replaced it might stand a better chance of transformation with something already standing ready to be that replacement. Money funds might well be fine in a limited role of strictly money dealing, but wholesale banking is far more than that including an entire suite of risk transformations and conduits for traded liabilities. Increasingly, banks themselves are telling the world that those vital activities are no longer profitable and they just don’t want to undertake the risks and efforts to carry them out anymore. If not them, who?

As it is, central bankers seem totally unaware of the necessity, as evidenced by their continued and now public puzzlement over global liquidity and treasury volatility. Connecting the dots has never been their strong suit, making this transformation all the more potentially disruptive. The eurodollar standard was these banks, and now these banks increasingly no longer want it.

Stay In Touch