What I set about to demonstrate in Part 1 was the visible spectrum of the wholesale system. In other words, you can see balance sheets grow and distort, with money dealing along with it, but that doesn’t cover the full dimensions on how and why credit production, especially through securities, bloomed as it did. This is, in many ways, the same process as has occurred in banking since the first bank was established – fractional lending. The problem in the wholesale model is defining what, exactly, is being “fractioned.” In traditional banking, someone deposits actual money and the bank “produces” several competing claims upon that money. They do so because they believe it is profitable and estimate not all claims will be presented for satisfaction at once.

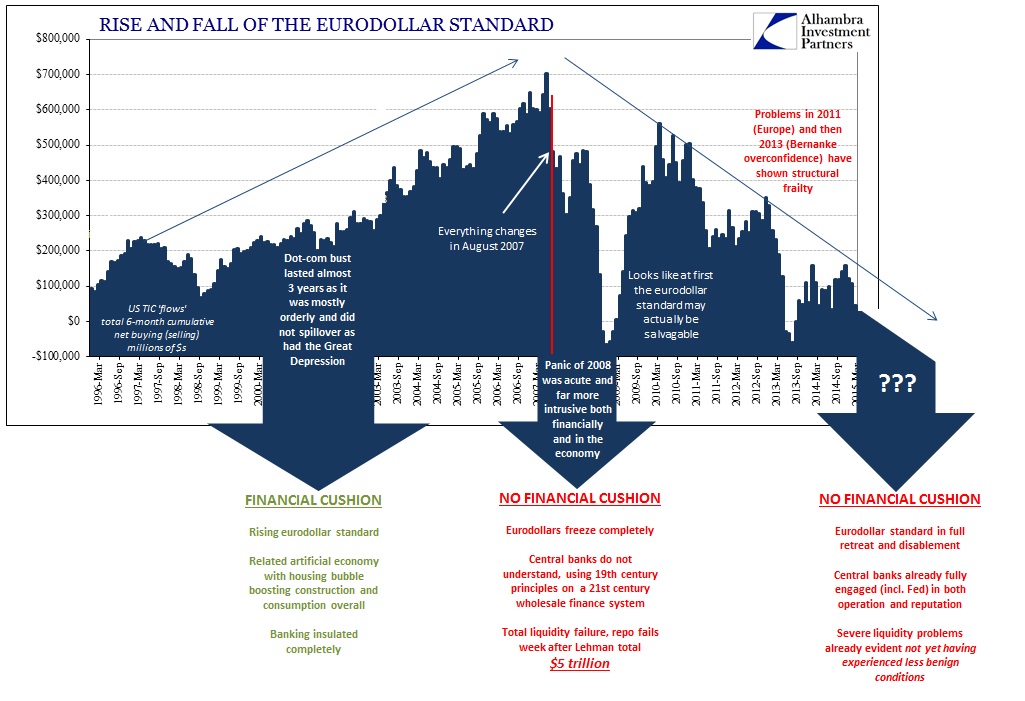

The problem in bank panics, thus, was how claiming (convertibility) events were clustered. The panic in 2008, beginning in August 2007, was essentially no different in terms of generic, systemic processes. What is difficult for many to comprehend is what was being claimed – it surely was not cash, currency or anything about real money. In essence, what banks sought was balance sheet risk factors that could provide “capital” relief.

In the modern, wholesale framework, the true “money supply” is far deeper than currency or even ledger “cash.” Because of the VaR-style framework for balance sheet construction, tied back to capital ratios and regulatory ideas about them, the ability to control risk management calculations amounts, in perfect kind, to a form of money supply; you might even go so far, as I would, as to recognize it as the form of money supply. If you can hedge at a definable price, you can define how much of a particular security or asset class in which to be able to invest. Once invested, that leverage is defined exclusively by the math!

If the “market” value of the hedges turn squirrely, that isn’t just a strict P/L problem for the income statement, but rather acts upon VaR, vega and all the rest. In other words, depending on a number of factors, without the ability to add additional hedges at desired prices and terms, leverage composition actually changes. In the case of 2008, because aggregate balance sheets were not attuned to taking on more risk, in the form of writing protection or the “needed” side of IR swaps, nobody could gain additional risk capacity to offset declining hedge effectiveness. The lack of derivative supply meant an exponentially greater decline in overall balance sheet leverage, and thus “money supply” contracted in the wholesale format exactly as it would have in a traditional bank panic.

This is what happened in miniature in 1998 with LTCM. Since, however, the FOMC and Alan Greenspan still thought purely in terms of banks rather than “banks”, they never did define it properly even though everything they needed to do so was right in front of them. They even discussed that very nature of the matter before them:

MR. FISHER. All this relates to the question of how this financing got to be so big and nobody realized it was happening.

CHAIRMAN GREENSPAN. What technically happens in that kind of model is that if we are resting on the last five years of experience during which the structure of the markets is essentially stable, that is, there were no severe contractions or even expansions, the covariances that we are going to pick up out of that five years are correct covariances for that population and that environment. What we were dealing with in the Russian situation, if we look at the data, was something that clearly was not a simple, steady state. In that environment, the coefficients in an econometric model either collapse to zero or to one. If we took the covariance matrix that would be implicit in that environment, it would give wholly different risk parameters than we would get in a system in which we are taking five years of special experience and saying the losses were never more than “x” on a daily basis. So what? That begs the question of what will happen in the future.

MS. RIVLIN. That is what stress testing is all about.

CHAIRMAN GREENSPAN. Yes, exactly.

VICE CHAIRMAN MCDONOUGH. We have to be very careful because as horrendous as this experience was, if we assume that the normal market is that the Russians are going to default once a week, the cost of capital would go so high that nobody would ever invest in anything.

All that translates into: if they correctly modeled actual risks, and by “they” I mean not just LTCM but all of Wall Street that was exposed on their $1.45 trillion derivative book, LTCM would never have attained the size and leverage it did. It was the opposite situation, as was repeated exponentially during the housing bubble – the cost of “capital” was made so low by the bad models that everybody would invest in everything and anything. Again, the math was actual “money” as it acted as a means to gain balance sheet size; making it “real” in the sense of finance becoming money.

The way in which that actually came about was, as I wrote in my lengthy column, mysticism and not even really math as conventionally understood as objective numbers and equations. Because LTCM was run by John Meriwether and featured both Robert Merton and Myron Scholes, they went around to Wall Street looking for wholesale financing and demanding their own terms. Who was going to turn them down and tell them their math was wrong?

MR. FISHER. It was something of a signature for this firm to insist that if a counterparty wanted to deal with them, there would be no initial margin. Not many other firms have gotten away with that.

MR. GRAMLICH. It goes to your bedazzlement effect.

MS. MINEHAN. I might mention something that we found out that came as a bit of a surprise, namely that some of the loans made by some of the large lenders were participated out. So, we see shares in banks in our District of both collateralized and uncollateralized lines to LTCM/P.

So, massive leverage for LTCM wasn’t even predicated just on math alone, but on the promise, backed by the logical fallacy of appeal to authority in the dual Nobel Prize winners,that ultimately saturated 1990’s finance. As Gordon Gecko points out in the movie Wall Street, “the illusion becomes real.” All that was necessary in this case was two balance sheet counterparties to agree to terms and away it all went; managed, badly, by VaR.

Somehow, this wasn’t the end of it as instead all of Wall Street turned into LTCM’s; banks became “banks” either through embracing the ideal or being taken over by it, as JP Morgan did all along the way. The missing piece of the “money supply”, the balance sheet factors that function in every way like currency, is derivatives.

I am going to present notional values of derivatives which should lead to caution in a couple of respects. First, most people get overly sensitive about the size of any “bank’s” derivative portfolio because the numbers are just, again, incomprehensible. Notional values do not denote total risk or potential loss. Not only are derivative positions often netted by offsetting transactions, they are collateralized, often heavily, which deprives notional calculations from specific and direct meaning in terms of risk. This isn’t to say that there is no risk conveyed, as surely the risks were still immense as revealed in 2008, only that you cannot determine it by simple notional values alone.

The second caveat is that changes in notional values can mean any one of several things. For my purposes here, and I think this is quite reasonable given history and context, notional values are used as a proxy for balance sheet “supply” being offered into the wholesale marketplace. In other words, I am making an assumption, which, again, I believe to be sensible, that an increase in “banks’” notional derivatives is akin to expanded wholesale “money supply”, or at least as a close approximation or representation for the quantity of balance sheet risk factors available.

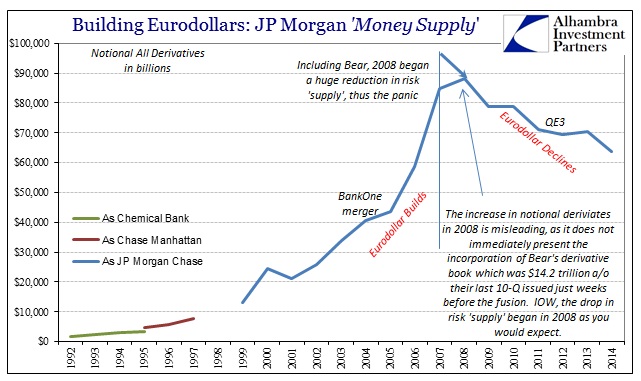

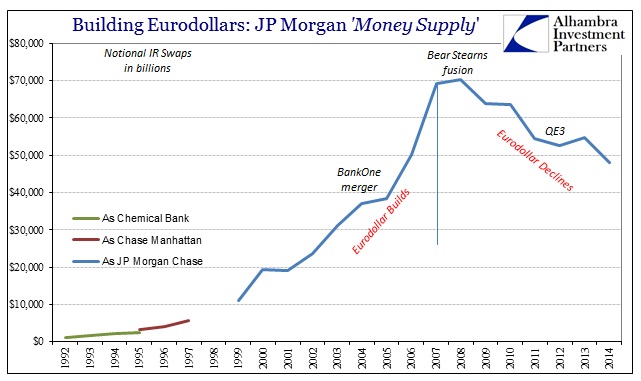

With that in mind, the track of JP Morgan’s notional derivative book could not be a more perfect representation of the rise and fall of the eurodollar standard.

It started around 1995, slowly at first, but by the middle 2000’s the growth was just insane. At the peak at the end of 2007, JPM’s derivative book was about $85 trillion. That was more than double the size of balance sheet mechanics offered into the market from 2004. If you ever wondered just how all that mortgage mess, the “toxic waste” of the housing bubble made it onto balance sheets with such high leverage and minimal financial disruption, here it is. Again, the math is like “money” in that controlling risk (or thinking that way) is exactly like leverage application.

In 2008, the panic was as much a shortage of hedging capacity and broad risk absorption factors, which we see above as the quite seriously shrinking notional derivative book. As JP Morgan “absorbed” Bear Stearns in March 2008 they also captured Bear’s derivatives, which totaled about $14 trillion. By the end of 2008, JP Morgan’s total notional was back down to $88 trillion, but that understates the difficulties of that time and ultimately why there was such sustained irregularity leading to outright panic (because the relevant comparison in terms of supply is not just the base of JP Morgan’s book at the end of 2007, nor even that plus Bear Stearns, but rather what 2008 “should” have experienced in terms of growth had there not been a full-blown panic).

Given what we know of the eurodollar standard post-crisis, the shrinking derivative book falls right in-line – the broadest view of global “dollar” liquidity and all.

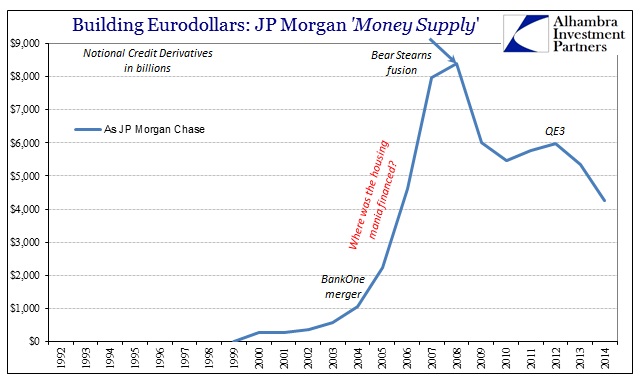

What is more impressive, or exasperating depending on your view, is the specific means for a lot of attained leverage for “toxic waste”: credit derivatives. “Banks” all over the eurodollar standard were only too happy to write protection, mostly in the form of credit default swaps, which, again, functioned as a means to expand systemic leverage along the lines as Alan Greenspan was fuddling with in 1998 – if the true math had been revealed in 2003, or earlier, instead of 2008, the “costs” of CDS, properly priced by more realistic models and estimates, would have been so prohibitive that no “bank” would have been able to touch the subprime structures and a great many of the mezzanines of even investment grade. Thus the great bubble, or at least a huge portion of it, might never have gained such immensity, just as LTCM would likely never have been much without Merton and Scholes.

As I wrote above, it is truly astounding. With just about $1 trillion in notional in 2004, there was $8 trillion by 2007 (the height of subprime and the worst “vintages”) and even more when factoring Bear’s unfortunately immense portfolio (which the firm never disclosed how much of that $14 trillion was in just the credit derivatives portion). Since so much balance sheet math was dependent, systemically, on CDS alone the shrinkage in “supply” caused inordinate and really self-feeding implosion – without any additional risk transformation being offered at all, let alone at an attainable price, that created actual P/L losses, since price irregularities could not be offset by additional risk hedging, all over “bank” income statements causing more havoc and so on and so on. The math is the ultimate eurodollar “money supply” and bad math leads inexorably to contraction. Mispricing risk, which was systemic under Greenspan’s conundrum, was the same as fractional lending expanding far beyond reasonable capabilities to take on even a minor shift in convertibility.

While all that is important in describing how we got here, it is also confirming the idea that the eurodollar system is beyond repair. It is not coincidence that gross notional derivative books are shrinking post-crisis as the eurodollar standard grows more and more unstable. With less balance sheet risk factors “on offer” as money supply, there isn’t much spare or even usable capacity to maintain liquidity broadly all over the “dollar” world. The difference between 2008 and 2015 so far is simply the level of selling pressure; in 2008, for various reasons, selling was paramount; in 2015, faith still holds fast.

QE has a lot to do with that, as is clear from the majority position in derivative books, interest rate swaps. I have covered this extensively in the past, but suffice to say JP Morgan at least (and Goldman Sachs) confirms the negative results after QE3 (banks jumped in to IR swaps on the word of Bernanke about QE3, and once betrayed in taper have instead removed even more balance sheet capacity from eurodollars; that is shown above for JP Morgan and is even more pronounced on Goldman Sachs balance sheet).

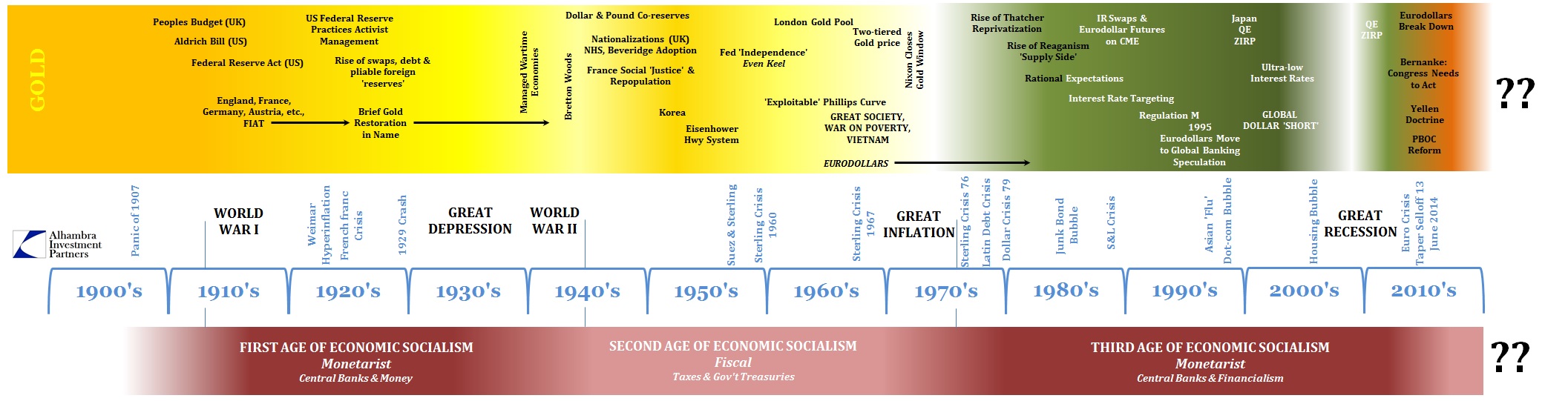

The math built the eurodollar standard, transforming banking into a far less tangible function. Money, or what I call the payment system, was inextricably intertwined with finance, and by intention. By merging banks with “banks”, “banks” would gain regulatory favor (again the math) which ultimately came in the form of TARP and TBTF. It was a colossal mistake, one that should have been apparent at least among the central planners of 1998, who still, somehow, claim expert status and ability enough to control and set marginal economic function even though they don’t know what a “dollar” is, what a “bank” is or how any of it actually works. Now that the math has been broken, however, no more VaR or “tail risk” suppression will fix it; the dysfunction appears every bit permanent.

What comes next?

Stay In Touch