It may be related or it may not, but the setup and decision by the Bank of England is far too close to the Federal Reserve to simply ignore or dismiss. While the FOMC added the word “some” to its policy statement at the last meeting to downgrade, really, its economic assessment, BoE accomplished much the same through different means. It was widely expected that two, perhaps three of BoE’s board would vote against holding record low rates but only one, Ian McCafferty, did this week.

The problem, or at least the current version of the same string, is the specter of “deflation.” Oil prices are singled out almost exclusively but that is a purposeful misdirection meant to try to reconcile the irreconcilable – that the economy is good enough for rates to finally, at long last, rise but that it must be delayed while oil oversupply or some such works out without unanchoring inflation expectations. That latter part is belied by the means with which BoE is now apparently delaying its exit/recovery signal – inflation is projected to be zero or negative in the near term and not reach the 2% target for almost two additional years.

If this sounds familiar, it almost exactly matches the projections made by the Federal Reserve. Even the actual state of the labor market in the UK, like the US, has been (rightly) called into question since monetary impotence in “inflation” is linked to wages and labor utilization (rather than the raw count of statistical jobs).

The potential for further deflation has not been ruled out. While it is not the Bank’s central case, its margin for error includes the prospect of further negative inflation prints in coming months. Lower-than-expected oil prices have increased this prospect.

The employment market continued to puzzle the MPC, with mixed signals including a falloff in employment growth, but, in contrast, more demand for new employees. Overall slack in the economy was still around 0.5 percent.

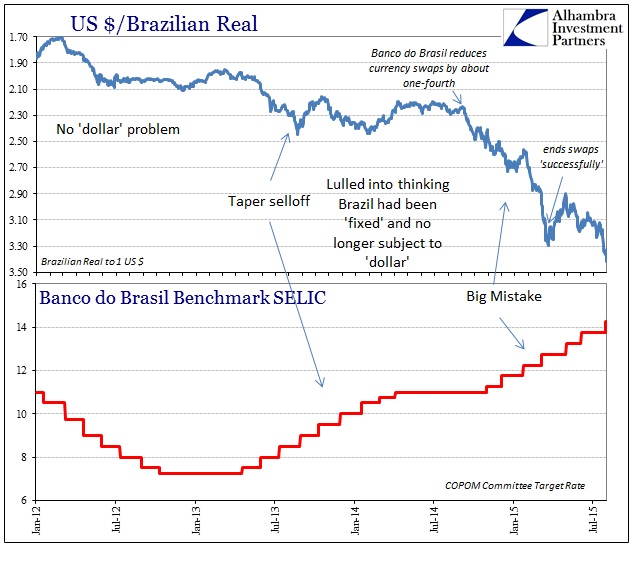

Again, it is a lot more than oil prices. We know that from a broad survey of assets affected by global finance, but it is being further emphasized by these various central banks that appear to have lost much if not all their assumed “influence.” I documented recently the case of the Brazilian central bank, in much the same position even if its primary tilt is in the opposite direction. That similarity despite negative orientation belies that oil prices are actually to blame, except insofar as they relate and demonstrate one outlet for the “dollar.”

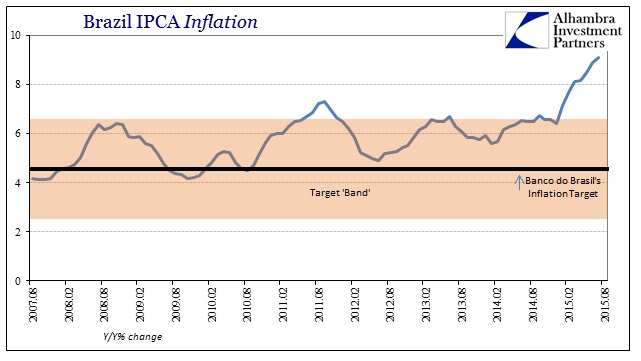

Where the US and UK find themselves unable to generate “inflation”, Brazil and Russia cannot get out of it – two sides of the very same coin. Banco do Brasil has “fine-tuned” its measures here and there over the past two years, but no matter what it did the trajectory was unaltered even if briefly deviated here and there. Brazil is in truly dire shape and Banco has been, essentially, powerless to accomplish any counterdemonstration.

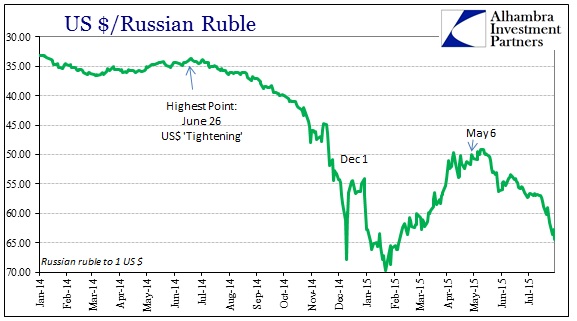

The same has been true of Russia, but with a very different narrative. The Russian central bank was thought earlier this year to be the very model of a modern major monetary interventionist in its actions over last December’s great ruble crisis.

Russia’s central bank won plaudits for stemming last December’s ruble crisis when it jacked up interest rates up by 6.5 percentage points to 17%. It has since unwound nearly all of that increase to ease pressures on Russia’s battered economy.

The Russians did what the monetary textbook says; up, down and all in between, like Banco, BoE, the Fed, BoJ, etc., it doesn’t much matter in the end. As soon as January, the Central Bank of Russia began to reduce interest rates as it seemed to have done its job, the ruble had become much calmer and believed irretrievably headed in the “right” direction. That was followed by a rate cut on March 13, again on April 30, June 15 and July 31. Notice that the last of those two rate reductions were taking place while the ruble (really “dollar”) was once more in motion toward harmful devaluation.

“Inflation” in Russia had slowed from a peak of 17% in March, so the Central Bank of Russia felt itself on the right track; by the June reading it was down to 15.3% before jumping to 15.8% most recently. Now, however, the ruble is collapsing again and there isn’t much the Bank can do about it as the last ruble crisis, regardless of the temporary reprieve, pushed Russia toward and probably already into full-blown and serious recession. Like Banco, the only option in the monetary textbook is to drastically raise rates again which will, like the real, have little actual effect upon the currency but make the recession that much more biting.

On the bright side, the fall in the ruble acts as a shock-absorber for the Russian government, which would otherwise face a big budget hole due to the decline in oil prices. More worryingly, though, the currency reacted badly to last week’s rate cut by the Bank of Russia, falling sharply. The central bank has already had to abandon purchases of foreign exchange in an effort to restock its reserves with inflation north of 15% and a deepening recession on its hands, it now has even less room for maneuver.

Faced with a weakening ruble—and if the selloff gains pace the way it did in December—the central bank may yet be forced to raise rates into the teeth of an oncoming recession; in last week’s statement it dropped a reference to being ready to continue cutting rates.

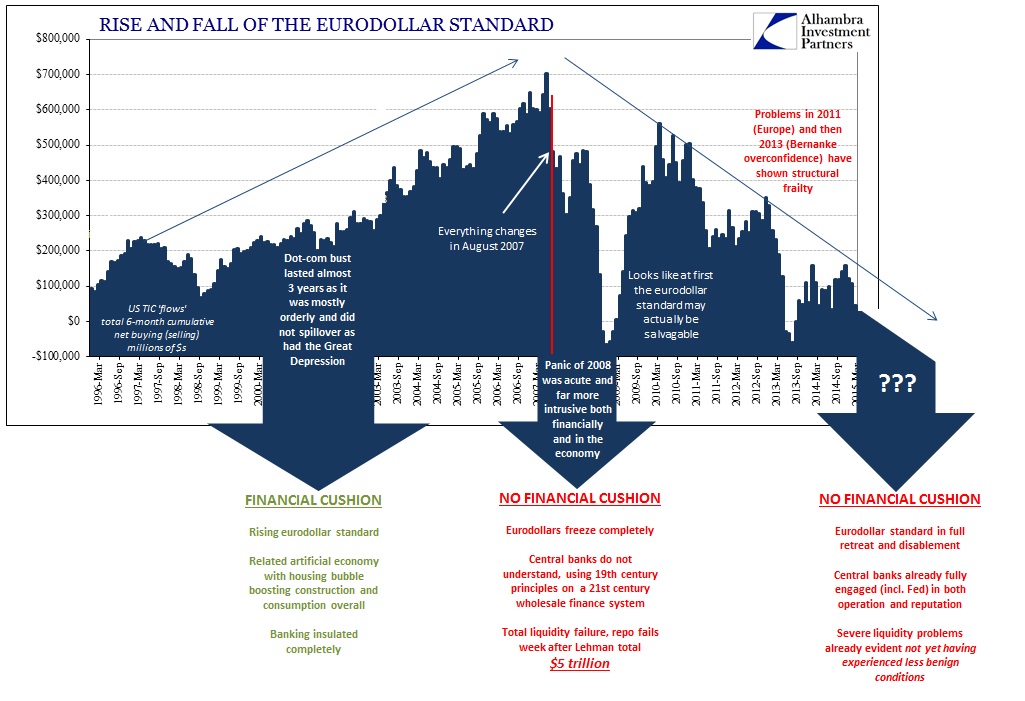

There really isn’t a bright side to any of this, which is precisely the point, as “oncoming” is being quite and predictably charitable. These media outlets simply assume that central banks hold authority and actual ability, but it is painfully clear and evident that such power is extremely limited particularly in comparison to the one uniting factor in all of this – the “dollar.” There isn’t anything the BoE can do to spark “inflation” so long as global financialism is dominated under the combined “short” of the wholesale arrangement. Banco and the Central Bank of Russia may wish to raise rates, but, again, it hasn’t done anything to deter “dollar” deterioration just as all the combined Fed and BoE QE’s have completely failed in bringing the official calculations to target (going on 3 years now).

The timing for a Bank rate increase is “drawing closer”, Mr Carney said in a news conference, but cannot “be predicted in advance”. The decision would be determined by looking at economic data, he added, including wage growth, productivity and import figures.

If it wasn’t specified in that quoted paragraph, you would have no idea whether those sentiments were being expressed by Janet Yellen or Mark Carney. Both Yellen and Carney have been saying the same things month after month after month and we still await the “lift off.” It isn’t any closer now than it was six months or a year ago, which is more a measure of futility against the “dollar” than anything else.

These central banks built themselves up by the wholesale model, mostly under the eurodollar standard, and are now finding that living by the bank is dying by the bank. It always seems so easy on the way up, especially when you have no idea what that actually was. Central banks used to be so inscrutable, doing no wrong, but the opposite on this side of the Great Recession reveals they were all just floating on the same tide of the “dollar” and just taking credit for it. As it now recedes, especially to a quickened pace, nothing works. – same as it ever was.

Stay In Touch