To illustrate just how badly Monday’s selloff (and yesterday’s late day reversal) seems to have shaken core confidence in the overriding narrative (ALL IS WELL!) you need only view the drastic reversal on what stock prices supposedly mean. With QE’s producing little or no tangible economic benefit, certainly nothing specific with which its proponents can easily point to, they have been left with some variation of “asset prices are up” or “stocks are rising so that means the economy at some point.” That end-of-the-line appeal is actually an arrangement decoded at the outset, so that it has survived and become the main counterpoint is as much expected.

Going back to then-Chairman Bernanke’s official QE2 “welcome”, published by the Washington Post on November 4, 2010, it was clear the order of stocks in the overall economic and policy construct.

This approach eased financial conditions in the past and, so far, looks to be effective again. Stock prices rose and long-term interest rates fell when investors began to anticipate the most recent action. Easier financial conditions will promote economic growth. For example, lower mortgage rates will make housing more affordable and allow more homeowners to refinance. Lower corporate bond rates will encourage investment. And higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. [emphasis added]

Just a few months later, in January 2011, in response to growing criticism about QE2, Bernanke reiterated this link regardless of direction or actual channel that governed really the orthodox view of stocks and the economy:

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said the central bank’s latest effort to pump money into the economy is partly responsible for the rise in the stock market, but not for the reason critics think.

The stock market rally that began last summer was fueled by the Fed’s efforts which improved U.S. economic activity, he said. But critics claim the Fed’s policy created a new asset bubble.

Those two provisions show very well the circularity that governs this approach, but for our purposes here it shows just how much orthodox views on monetary success tie to asset prices, stocks in particular. For them, it does not matter if stock prices lead to better economic outcomes or whether better economic outcomes lead to higher stock prices – they are all one and the same to this view that has prevailed upon the “bull” market that began back in March 2009; somehow, some way, stocks and the economy will at some point converge even if it means stock prices rise first and the economic surge comes later (how much later is the point).

At the economic turn in October 2012, only a few weeks after the FOMC was “forced” into a QE3, the asset price methodology was ubiquitous in its reiteration. Stocks simply skyrocketed thereafter, again in described anticipation that at least the “how much later” conjunction would be significantly lessened by the renewed monetarism – while conspicuously and strenuously denying that the very fact of a third (and then fourth) QE might hold very different interpretations.

“It’s pretty clear that the stock market is the most important transmission mechanism of monetary policy right now,” said Peter Hooper, chief economist at Deutsche Bank AG in New York. “That’s where you’re getting most of the action in terms of lift to the economy. It’s the stock market that’s going to have to be carrying the load.”…

“They’re very explicit about trying to create financial conditions to try to support the economy,” said Ward McCarthy, chief financial economist at Jefferies & Co. in New York and a former Richmond Fed economist. “It’s become more explicit out of necessity, because the Fed doesn’t have the Fed funds rate to use as a tool because of the zero bound.”

Even the brokerage industry, missing no turns to talk their book, was explicit about stock prices as at least that forward indicator on economic fortunes especially in the case where equities might not match economic performance right away. From Charles Schwab in April 2013:

The bottom line is that the stock market, as a leading indicator, tends to launch into rallies and/or corrections around economic inflection points. By definition, a rally-inducing inflection point occurs when economic growth stops falling and begins to rise (green dots), which means GDP growth is at its worst. This is part of why new bull markets can breed rampant skepticism.

A great example of this relationship, and the power of possible inflection points, was the performance of Greece’s stock market last year. The country’s economy is in a near-depression amid its debt crisis, yet the Athens Stock Exchange was the best-performing stock market within the European Union in 2012—up more than 33%!

The reference to Greece in that context gives away where all this is going, especially about what share prices in general actually mean away from all this orthodox monetaristic nonsense. But before that, even Janet Yellen has been known to seek out comfort in equity prices as if to justify both what the Fed has done and how that will at some point produce what everyone really seeks. In her May 2014 testimony before Congress, she goes back to Bernanke’s original formulation, stocks and economy:

A faster rate of economic growth this year should be supported by reduced restraint from changes in fiscal policy, gains in household net worth from increases in home prices and equity values, a firming in foreign economic growth, and further improvements in household and business confidence as the economy continues to strengthen. Moreover, U.S. financial conditions remain supportive of growth in economic activity and employment.

This was the same Congressional appearance that, in the Q&A that followed, produced one of the only memorable questions from an oversight perspective:

REP. KEVIN BRADY I know my colleagues will ask about today’s Wall Street Journal where noted economist, Federal Reserve historian Dr. Alan Meltzer, makes the point never in history has a country financed big budget deficits with large amounts of central bank money and avoided inflation. My worry is that the track record of central banks, including the Fed, in identifying these economic turning points and acting quickly to prevent inflation, that track record is not as good as we would like. So, forgive me for being skeptical. I believe we need more specifics and a clear timetable on the comprehensive exit strategy.

As we know now, “exit strategy” was more itself a policy tool than actual plan and in the wrong direction, apologies and due respect to Dr. Meltzer. The reason for that is also becoming rather known, as the links between stocks and the economy, for all the posturing and rhetorical certainty unleashed these past seven years, are especially tenuous under great financial imbalance to bubble proportions. That much is easily intuitive without the need for vast and dizzying regressions on the subject, but what is important again here today is how that past conviction about the close relation of stocks and the economy suddenly departed this week.

As the direct linkages to the American economy and markets are not immense, some strategists are questioning whether the angst over China is overdone. Economists at Citi, for instance, did not see the chaos stemming from China as a big enough factor to derail a rate hike from the Federal Reserve in September. Meanwhile, Torsten Sløk , chief international economist at Deutsche Bank, indicated that he hasn’t “seen a smoking gun chart showing why a slowdown in China will have a significant impact on the U.S. expansion” and suggested that the current slide made for an attractive buying opportunity.

And:

First, keep in mind that stock prices aren’t the best measure of the economy’s overall health. Remember how crappy the U.S. recovery felt back in 2010? Well, shares were surging then. And while a bull market might slightly benefit the economy as a whole through a modest “wealth effect”—meaning that when portfolios rise in value, people feel richer and spend more—most families simply don’t own that much stock.

That second quote (from Slate of all places, and judging by the tone and writing you can infer the sophistication of their target audience) comes under the subheading “Is The American Economy Screwed?” Obviously, given that stocks no longer matter much apparently, their answer is “not really.”

Bubbles are really just rationalizations that become inescapable to those just beyond their surface. In this case, it is more than just stocks and asset prices (clearly corporate debt) as it leads into this impenetrable fog of “nothing can be bad anywhere.” As indication after indication falls apart or by the wayside, month after relentless month smacking down “transitory”, there are these supposedly logical counterpoints that intend nothing but to maintain the narrative in the public mind (rational expectations being practiced). This changed attitude about stocks obliterates the idea that asset inflation was even a rational counterpoint in the first place, as if it in any form can be disregarded whenever most convenient.

On the way up, prices were all that counted because there was nothing else to support monetarism; now having sputtered into a critical point of potential awakening to the very real downside they don’t matter at all or are at best weakly associated with the economy? What should have been taken at QE3 is seemingly quite applicable right now, namely that “how much later” might be shifting into “perhaps never.” Like the Fed that won’t pull the trigger on a rate hike, the modifying sway in action against their preferred account is all you need to know about what’s real and what remains still fantasy.

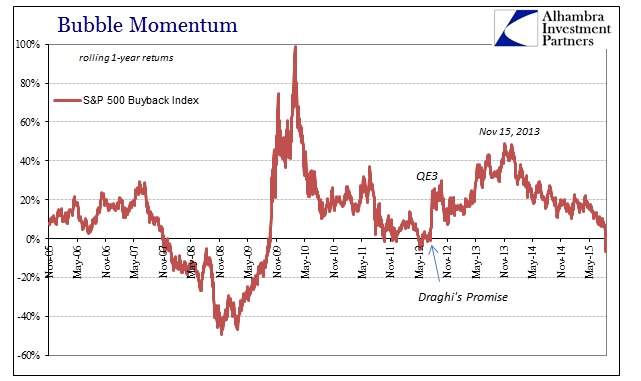

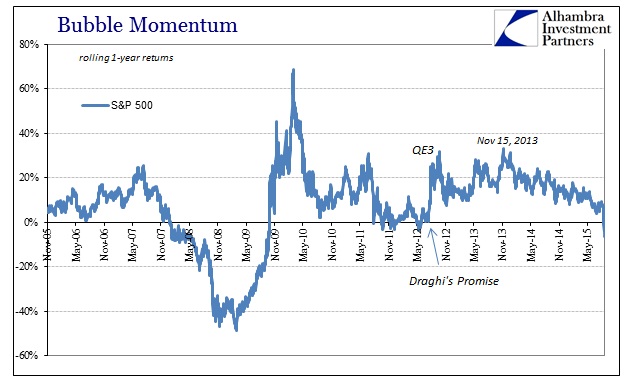

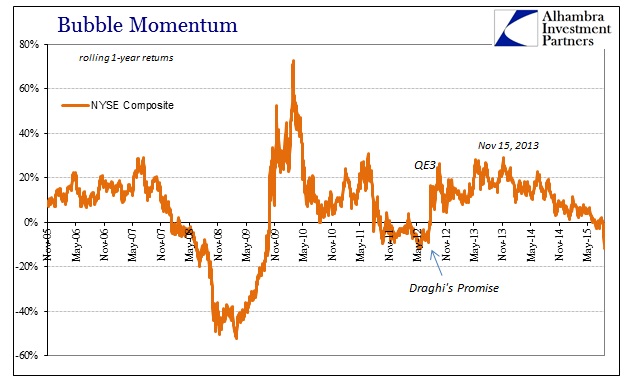

Back on May 6 this year, it was Yellen herself that provided a brief moment of clarity to that end. As if right on cue, stock momentum has faded from the time when she remarked about equity valuations being “generally quite high.” In an asset bubble formed of aging rationalizations, momentum is not just a key component but perhaps the key:

That is the danger of the lack of momentum, as momentum serves as an indirect proxy for belief and rationalizations. Once they fade away it is harder to deny reality any longer. At the very least, top or not, it seems as if investors all across the financial landscape are themselves are losing faith not just in monetary policy and the economy but maybe even the idea that this was anything more than yet another bear market rally. Even Janet Yellen might think so; after all the “dollar” beat her to it.

Momentum counts for more than just price action, as we can well observe this week, extending to accepted “wisdom.” Even bubble investors will get tired of only waiting.

Stay In Touch