Michal Kalecki was a Polish economist whose work in the 1930’s earned him (for what it may be worth) the distinction of being Keynes before Keynes. In other words, because Kalecki was publishing papers and giving lectures in Polish rather than English, his arrival at the same conclusions and outlooks before Keynes in the UK was largely unnoticed. He was highly influenced by neo-Marxism which led him to the same pursuit as which modern economists have cornered themselves (this is not coincidence), in search of a quantification theory using statistics to order and identify all parts of the economy.

He started with the simple Marxist divide between labor and capital, forming ideas about how one influenced the other (and bank and forth). Eventually he created what is known as the Kalecki Equation which says that corporate profits have to be equal to investments minus capital “consumption.” Further, he contended that it was the latter part of that equation which determined the former; the question of profits shaping investment and consumption or the other way around:

“The answer to this question depends on which of these items is directly subject to the decisions of capitalists. Now, it is clear that capitalists may decide to consume and to invest more in a given period than in the preceding one, but they cannot decide to earn more. It is, therefore, their investment and consumption decisions which determine profits, and not vice versa.”

There is one assumption he makes here which is actually germane to the issue of serial asset bubbles in the 21st century, so setting aside any political framework (and implications) there does appear a basis for the theory in US economic circumstances.

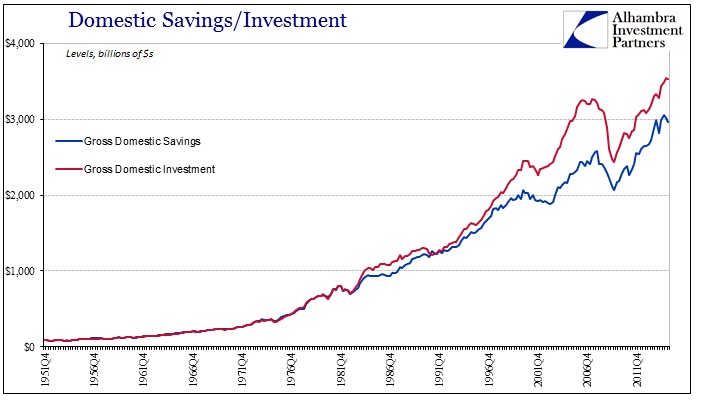

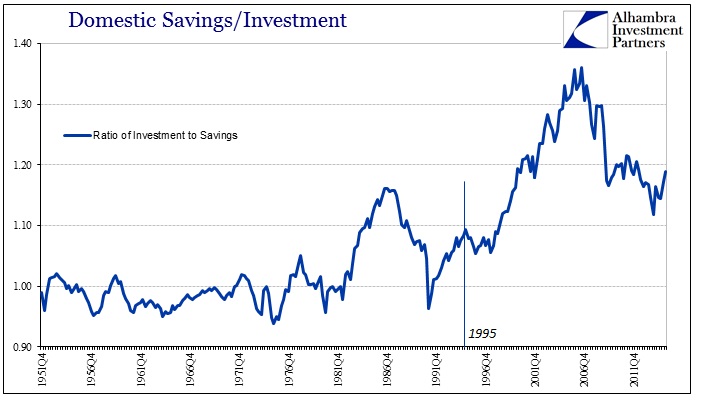

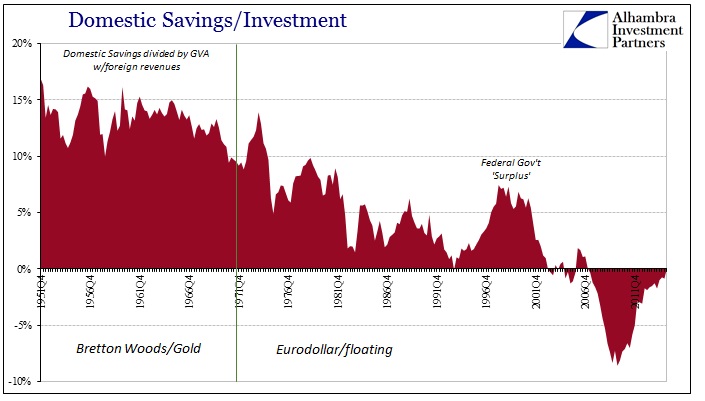

Until the early 1980’s (again, no coincidences here) the relationship between savings and investment was nearly straight 1 to 1, with only minor variations. Savings are defined here as the net savings of the domestic sector (households, corporate business both financial and non, noncorporate business and all levels of government) plus the consumption of fixed capital (and a statistical discrepancy) while investments are all that plus “foreign savings.” In other words, what is being introduced, starting at (assumed) the end of the Great Inflation is “foreign” finance.

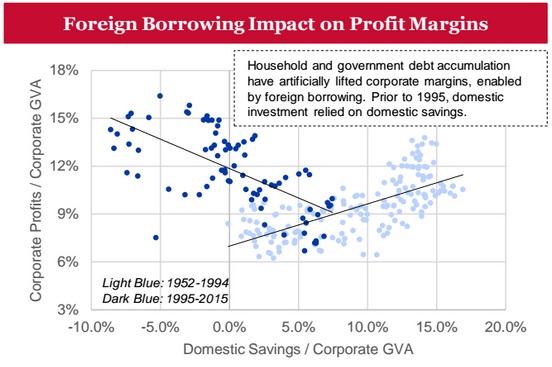

When we analyze the serial asset bubbles of the 21st century, it is often limited to financial circumstances and implications while the character changes in the real economy get pushed aside or to more qualitative discussion. Matthew Weaver of Ford Fund LP pointed out to me the obvious shift in even the quantification of corporate profits as funneled through the Kalecki equation – and thus the real economy effects of this monetary influence.

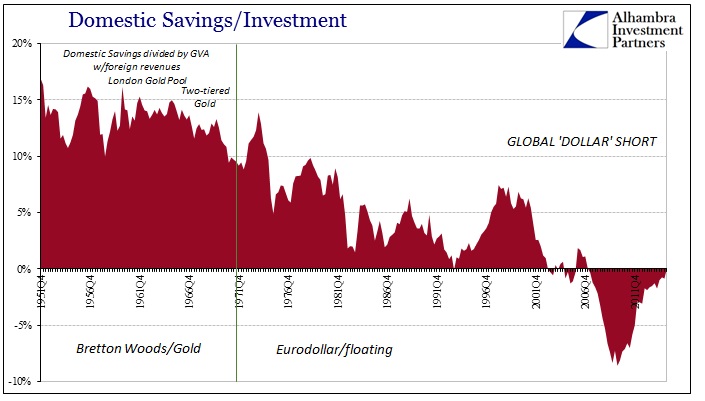

In other words, Kalecki simply assumed that savings were savings, a quantity that is derived from real economy activities. In the case of post-Bretton Woods international finance, that isn’t a solid postulation by any means. It is, of course, the position of Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke (global savings glut nonsense) but there is a much simpler and intuitive explanation than a sudden and sharp rise of “foreign savings” without good reason for that appearance and flow to the US. This is, of course, the intrusion of the eurodollar after 1995 flowing back into the US where conventional statistics (such as the Flow of Funds) are unable to decipher their exact nature. Instead, economists use anachronistic but safe (to them) assumptions about the obvious change rather than seeing it for what it was.

As Matthew points out, prior to 1995, gross domestic savings had been negative (flow) in only one quarter (Q3 1993). But, as you can see plainly above, domestic savings had been on the downslope going back to the late 1960’s (the Great Inflation in almost its entirety) coinciding with the tremendous monetary shifts globally. With government deficits taking up the balance of those savings prior, any increase to corporate profits (again Kalekci) could only come with a measured increase in household or financial “savings.” It was the latter that was truly opened by the eurodollar standard’s adoption (in practice) in the 1970’s.

In other words, the financial system was no longer limited to actual hard money and savings (the economic act) but actively began to manufacture them (ex nihilo) through the various infusions of eurodollar finance. That had a noticeable effect on the go-go 1980’s, but was truly unleashed in 1995 with VaR, JP Morgan’s RiskMetric’s and the math-as-money wholesale takeover.

As Matthew’s work easily demonstrates, the corporate sector freed from actual savings has gained the greatest benefit; since “savings” in general no longer provided the full basis (and thus limitation and correction) on corporate behavior and even general economic behavior, the US economy, built on this eurodollar money-as-debt system, flowed beyond all prior boundaries. US households could become, as the government sector, highly indebted without an immediate or determined organic restraint. Flipping that around, it suggests (strongly) that all the debt creation fostered in this global financial transition has flowed almost directly to the corporate sector’s bottom line.

That makes intuitive sense given that debt financed consumption would inevitably be one-sided where the corporate sector doesn’t reciprocate in terms of productive investment flowing back to households as wages. The imbalance would have proved unsustainable long, long ago where true savings (as derived solely from wages and earned income) would have declined without the “surplus” of debt to fill in the deterioration. It was so prejudiced, in fact, that it could only continue where the foreign “money supply” intrusion kept growing (suggesting an “answer” to the scale of the Great Recession as well as the global economic condition in this “recovery”, especially after the 2012 slowdown that followed the eurodollar disruption from 2011).

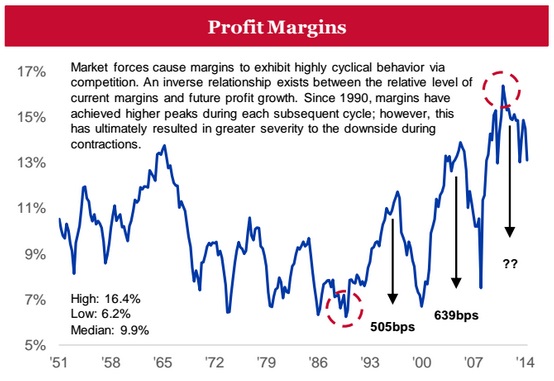

That has profound implications as the US economy, since the early 1980’s, has become one supposedly focused marginally upon only consumption. That in turn feeds further financial imbalance as the basis for at least part of the stock bubble (and the corporate debt bubble of late) since corporate profits have been viewed as solidly economic rather than more purely financial; despite the incongruous nature of profits vs. wages going back at least the last 15 years. If the eurodollar intrusion starting in 1995 is going to be reversed (it certainly looks that way more and more), then profit expectations are wholly unrealistic as are, unfortunately, economic expectations.

Because the eurodollar manufacture of “foreign savings” was directed at consumers more so than businesses, it is this consumption imbalance that developed the heights of this mischaracterization. That would include orthodox economists’ assumptions about productivity (their ongoing “mystery”) as well as the bubble mechanics. In short, the corporate profits generated the past few decades are predicated not on a “new normal” of consumption and sustainable dynamics but only the bastardization of “money” into artificial supply disguised as “savings” which redirected economic flow into a one-sided bottleneck. Removed of past monetary restrictions, which is what eurodollar finance truly was in its most basic sense, it was able to reach massive proportions regardless of what the FOMC was doing about the federal funds rate. It wasn’t just a financial shift, these serial asset bubbles, but a truly unappreciated gigantic interruption in basic economic construction (and, as we are seeing more and more, of much poorer economic circumstances broadly).

There are innumerable potential problems for a total eurodollar reversal. This might be close to the top of that list in both short and long-term considerations. While I don’t believe it possible to quantify the economy, as Kalecki and all the rest, there is still some use in these figures and comparisons in confirming suspicion about trends. Again, as even Greenspan/Bernanke note the intrusiveness of “foreign savings” they are recognizing the effects without being able (by ideological blindness) to identify the cause. There is and has been no increase in foreign savings, only the maniacal offshore debasement of the “dollar” that continues to escape their “legendary” notice.

Now to the “unexpected” economic and financial consequences as such “savings” reverse.

Stay In Touch