Every once in a great while, you run into a mainstream article or news story that actually breaks through the thick cloud of conventional nonsense that passes for expert commentary. Despite clear signs about why people the world over should be worried about China, day after day we are told there is nothing to worry about. Their currency is in no trouble because, supposedly, they learned from the Asian flu of 1997 and 1998 and hoarded the largest mass of forex “reserves” ever conceived.

China’s $3 trillion-plus in foreign currency reserves, the biggest such stockpile in the world, would seem to be a gold-plate insurance policy against the country’s current market chaos, a depreciating currency and torrent of capital leaving the country.

And then the truth of it, which is much, much different:

Then there are other liabilities that China needs to cover, such as the nation’s foreign currency debt to finance and manage imports denominated in overseas currencies. When those factors are taken into account, some $2.8 trillion in reserves may already be spoken for just to cover its liabilities, according to Hao Hong, chief China strategist at Bocom International Holdings Co.

I think that estimate far too light, but that it is being suggested at all in this context is noteworthy. Forex “reserves” are not what they have been proclaimed to be; nor is the “dollar” system that leads to this mismatch between function and interpretation. China has $3.3 trillion in foreign “reserves” but they are not that. They are instead only one half of the picture, one side of a double-counted ledger. What is on the other side is much more of a mystery and it is that side that holds both all the answers and all the monsters.

Given all that has taken place this week, it is unsurprising to find the PBOC by Friday speaking about more soft measures that might be taken to curb the turmoil. But when you appreciate their suggestive stance for what might be between the lines of guarded wording, it only raises more substantive questions. First, in a statement issued today, the PBOC once more proclaimed its commitment to a stable currency which again more than suggests “devaluation” is devastating financial withdrawal. They claim that they will allow more interest rate liberalization to account for it, but that, too, speaks more about the desperate situation that they would at this late stage essentially appeal to outside forces. This cannot be overstated (as I noted here; subscription required).

Even more revealing, however, was that the PBOC promised, cryptically, to revisit some of the “stimulus” that was used in 2014:

The central bank will use medium-term loans, and pledged supplementary loans and credit policies to support key areas of the economy.

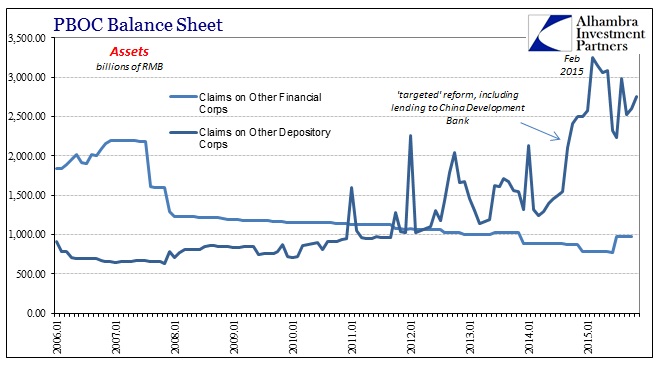

The question isn’t why would they claim to go back to these programs but rather why they stopped in the first place – right in March. Recall the basic mechanics of the PBOC’s balance sheet, both sides. As the asset portion declined in forex, the very basis of Chinese “money” and bank reserves, starting in the middle of 2014, the central bank had a choice to make: either allow that asset decline to flow through into a liability decline or do something else on the asset side to fill the gap. They chose in 2014 as they did in 2011 and 2012; “something else” in the form of PSL and SLF (Standing Lending Facility mostly to China Development Bank). But, as I wrote earlier today, that wasn’t a perfect substitution as, in fact, it amounted to significant redistribution of internal RMB liquidity:

It sounds inordinately simple to just “buy” something else and move on about the country’s economic business, but doing so is tantamount to direct redistribution. Unlike central banks outside of China, especially the Bank of Japan by contrast, redistribution of this kind is very much appreciated as fraught with all sorts of potentially devastating consequences. Perhaps the clear difference in avoiding monetary redistribution as much as possible in China is that China is already itself the product of such engineering in so many places. But even with that reluctance, the PBOC carried out short-term liquidity operations, especially “Claims on Other Depository Corporations” which include special loans and monetary schemes tied to the major state banks, like China Development Bank (CDB).

The PBOC was allowing the generalized liquidity market in internal RMB to take the hit of the forex withdrawal from the “strong” or “rising” “dollar” (or whatever you might want to call it without all the requisite quotation marks) while redirecting RMB to “targeted” financial firms like China Development Bank. I have no doubt that was tied to their reform agenda, to bring down the monetary resources supporting what Chinese authorities likely thought was a strong avenue for asset bubble growth. They clearly thought that by channeling through more productive (targeted) means overall liquidity would not suffer. But then “something happened” which turned it all upside down, and from which the PBOC has yet to recover:

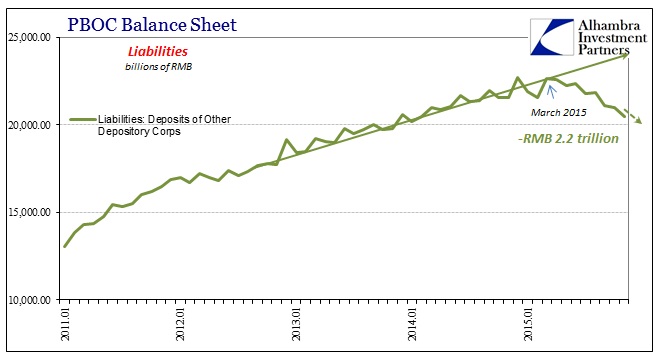

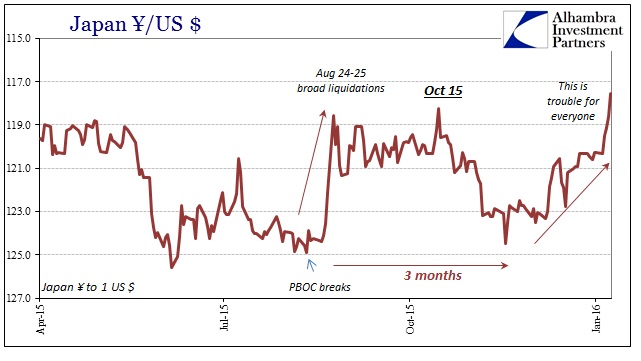

In March 2015, all that changed. The exact catalyst remains unknown, but what we do know is that the liability side, those RMB bank reserves, stopped in their tracks. Since March, “Deposits of Other Depository Corporations” have been in reverse, and often heavily so. The amount through November, the latest figures, has been an enormous RMB2.2 trillion, or almost 10%! If we don’t know exactly why the reversal, what we can reasonably infer is that “something” changed of a greater magnitude that would essentially undermine, and eventually destroy, PBOC control of its own internal liquidity regime.

That much was apparent almost straight away. The exchange rate between yuan and dollar starting on March 19 stopped. I don’t mean that there was no longer any exchange taking place but rather that the exchange rate volatility dropped almost to nothing; the exchange price in dollars moved almost perfectly sideways thereafter.

And now the PBOC is using external appeals, though they make it sound as if they are moving toward “liberalization.” Instead, put altogether like this, it looks increasingly the case that the PBOC has run out of resources; they have reached the end of their liquidity tether, having blown through since March last year what was likely left of their abilities. I don’t know for sure that is the case given the awful opacity and hidden components, but my gut tells me that what was desperate trouble in March is something much more serious now.

One piece I keep coming back to is Japan. The fact that Japan and yen are now more closely tied than ever signals, to me, further anecdotal suggestions along these lines. It isn’t quite evidence because I would prefer to establish a chain of data the fixes one end of the Asian “dollar” to the other (Japan to China and back again), and so far it has proved quite difficult to accomplish. But when you put all these pieces together, especially the very important money market data, both here and there (subscription required), the compelling narrative that leaps out is a downward spiral.

I think the PBOC is truly running out of options. If they were so fraught in the five months after March to have abandoned intentional redistribution, and then completely pancaked by the “dollar” in August, what are they now, having done all that they have done and to no gain? The “dollar” still runs and it sounds very much to me like the first cry for international and global help.

Stay In Touch