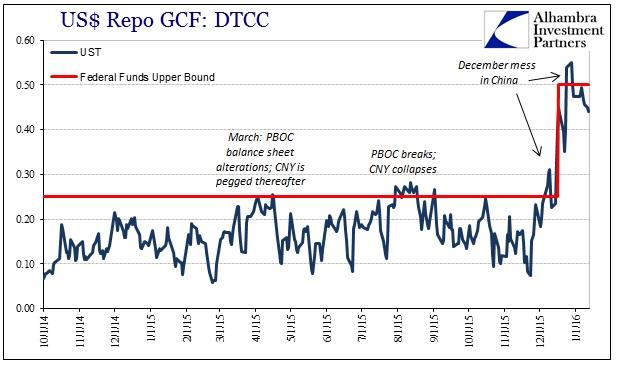

Behind our new paywall, I have been documenting the behavior of “dollar” money markets as they relate to China and elsewhere (global, general liquidity) but recent data in repo demand a more open airing. There are numerous indications that US$ markets are a total mess, none more so than repo. That starts with GC repo rates that remain above the effective federal funds rate, but below LIBOR. One of those rates must be “wrong”, and that doesn’t preclude the possibility that they all are. Secured vs. unsecured is a hierarchy; repo should trade lower than unsecured federal funds. If repo is more suited to where LIBOR currently is, then federal funds is fragmented and itself a mess.

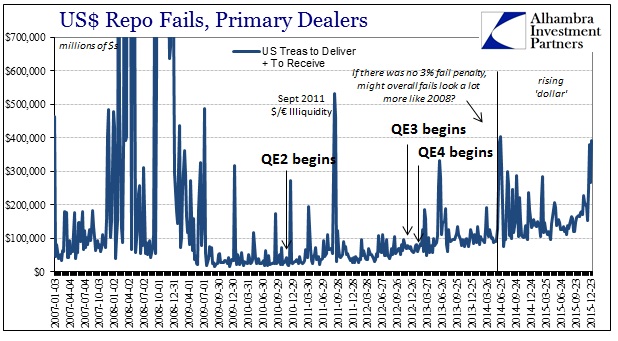

It is repo fails, however, which make a complete mockery of everything that the FOMC claims top to bottom; the RRP, IOER, normalizing behavior, all of it. Fails data disproves almost everything about the money market regime the FOMC has fictionalized, and it tells us a great deal about why things are the way they are right now. This is not just about the Fed’s ability to control some rate corridor during its exit program, it is more basic and concerning in that the Fed, once more, proves it doesn’t understand modern money and banking, and thus the very agents it assumes will provide its mechanism for imposing control and order. The implications of that are dire; from everything about assumed “currency elasticity” to renewed fragmentation as money markets are not a singular mass.

Start with the RRP itself; it was supposed to have a dual role in setting a money market floor and providing at least an emergency measure of collateral distribution for repo (especially via non-bank channels). The floor has been violated on several occasions, including three of the last five trading days (why would you lend unsecured in federal funds at 22 bps, as someone did on Monday, when you could “lend” at 25 bps to the Fed secured by UST’s in the SOMA?). But in terms of a more vital function, the lack of RRP usage as a collateral scheme is completely damning.

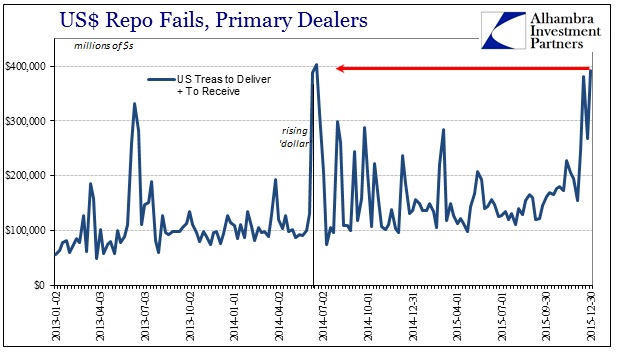

Despite the FOMC’s promises to open up all of the unaccounted SOMA holdings (no a priori cap), repo fails in the latter half of December reached highs not seen since June 2014 and the announcement of the opening act of this still-unfolding “rising dollar” tragedy.

If RRP were an effective alternate means of distributing collateral, we should see no such surge in repo fails; not least of which is because fails are effectively a -3% repo rate spread across hundreds of billions in repo trades. Again, the repo conditions in December were as bad as June 2014, which undoubtedly signaled the start of the money market disruption that is called the “rising dollar.” And that makes this mess in December 2015 all the more maddening, because the RRP was under full testing parameters at that time; meaning the Fed knew it didn’t really work as intended. That period included the end of Q3 2014 and then the clear and global funding disruption (shock) that presented itself just two weeks later in the events of October 15, 2014.

I wrote on October 1, 2014, that the RRP was a “fairy tale”:

“We don’t exactly know how it will work” should be stamped upon every message coming from the policymaking apparatus from this point forward, and then retroactively applied to every message in the age of risk and rate repression. Action in short-term money markets has heated up yet again, and that is not a positive statement toward vital function…

The reverse repo program was supposed to provide “aid” toward establishing a hard(er) floor for rates. It obviously failed with the persistent spikes in repo fails, which denote effective repo rates at something between 0% and -3% (and closer to the latter than the former). Collateral, that interbank currency, is not getting out of the Fed “silo” (its vast SOMA holdings) to conduct business as needed.

The conclusion of that piece should be recognizable today:

If the system does not function as intended now, under if not ideal circumstances than certainly far from stressed, how is it going to perform under real strain and duress? Might that be a significant factor that is beginning to wind its way into the larger dollar system, the venue of the global dollar short? This bears repeating, maybe even included after the perpetual warning I asserted above, that liquidity is not what is evident right now, but what is expected when the things are really going wrong. “We don’t know exactly how it will work” is a hell of a liquidity program for that eventuality.

It is reasonable and fair to say that we have now arrived at “that eventuality” and the RRP is functioning now just like it did then; and that’s a huge problem. Just ask China.

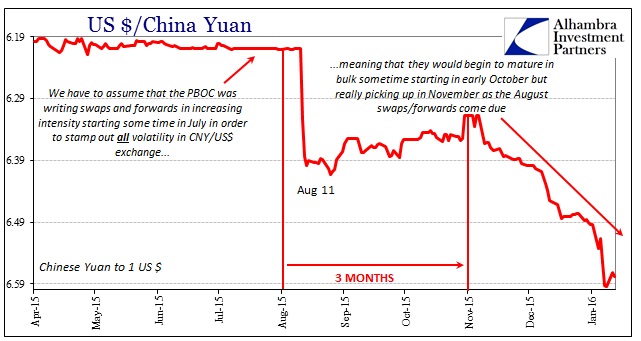

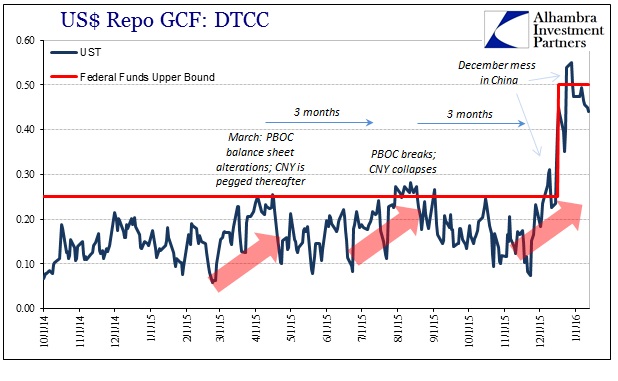

I think it is repo, more than anything, that puts the spotlight on the Asian end of the “dollar.” We already know that collateral must be short outside the domestic system (the “other” RRP, the foreign “accommodation”, as I have been highlighting behind the paywall, is in overdrive) and that general unsecured liquidity (LIBOR) offshore is elevated at a curiously high spread. But repo GC rates in their highly unusual positive spread to whatever part of the federal funds corridor only seems to happen when China is in great disarray (is China the cause or the effect? I have little doubt the latter).

What you notice just in glancing at the chart above is the regularity of these repo spikes after March (as processes or intermediate trends rather than individual, daily prices). It is something I have noted before as the tell-tale signs of PBOC deployment of wholesale factors of whatever derivative form(s). The connection to US$ repo from any potential PBOC forward at maturity is the simple act of borrowing “dollars” to “replace” what the central bank already sold into the market (to calm it then without regard to what it might look like at maturity).

The problem is that these money markets are acting individually without any kind of active participation which would (and should, if the FOMC is to be believed) solve, via arbitrage, just these sorts of irregularities. That clearly hasn’t happened, and repo fails (along with shallow T-bill rates) prove that repo is utterly distinct from that process. There is no active intermediation that is bridging these divides in collateral let alone raw money market flow.

That, too, is a problem I foresaw going all the way back to when the RRP was first announced in this context in September 2013:

It [the theoretical design of the RRP] would also provide a channel for collateral to flow into the marketplace at the Fed’s discretion. Since non-banks and banks alike can bid for however much they wish at these reverse repo auctions (full allotment), they would then possess enough (theoretically) collateral to satisfy market demand. In other words, the Fed controls the margins of the US treasuries in its balance sheet inventory so that collateral is “priced” not to yield negative rates, or even below the IOER or whatever policy target it seeks. Right now, since the effective federal funds and the GC repo rates trade below the IOER floor, owing to the presence of non-banks, this would be a means to enforce further control over short-term rates and make the IOER floor an actual policy framework like the ECB “corridor”.

I am not as sanguine as some about how that might work, particularly in a climate of rising fear, but it does offer the possibility of using the SOMA holdings to alleviate a “market” collateral shortage.

The weak link here is that the entire plan is dependent on the Fed being correct in its perceptions of market conditions and that it can tailor its response to actual functions. It would still be dependent on non-market, bureaucratic decisions, the kind made during the months of tension before actual panic in 2008. It would also introduce an additional collateral “rental” fee that might not be calibrated correctly. In short, this plan depends on the Fed to correctly surmise rough patches and their causes, and then correctly deal with them in effective doses of policy. I don’t see what confidence that inspires.

Again, we are way past concerns about the Fed controlling interest rates on their way to fulfilling normalcy; these are testaments to the huge and vital gap between monetary theory and monetary practice under increasingly strained existence. So much of what liquidity that remains is predicated on the idea that the central bank will be able to provide “elasticity” should it ever be truly necessary (again). Money markets, and repo fails in particular, show without any doubt that monetary policy cannot, and that it doesn’t know what it is doing – at all. This wouldn’t be suitable for 2007 (which was the entire point; legislating the last crisis) let alone 2016.

This is the essence of the “fingers crossed” strategy that is perhaps the inevitable, extreme end of rational expectations theory. The Fed simply says it and hopes that the market does it. When shown that isn’t happening, the Fed responds by changing the subject and hoping not enough people notice. That’s the problem with China and why it may be a paradigm-altering outbreak of the same “dollar” issues; you can’t ignore it and these repeated intrusions erode confidence in general, if not specifically money markets, about monetary policy.

The RRP was a fairy tale under testing in September and October 2014 (to which the Federal Reserve and US Treasury Dept. blamed some computers for October 15) and unsurprisingly it still is under full rollout and live action. Unfortunately, that vicious connotation applies far beyond the RRP’s very limited range, standing for the competence of monetary policy and policymakers more broadly. From there, you can start to appreciate the increasingly unsteady world around us.

Stay In Touch