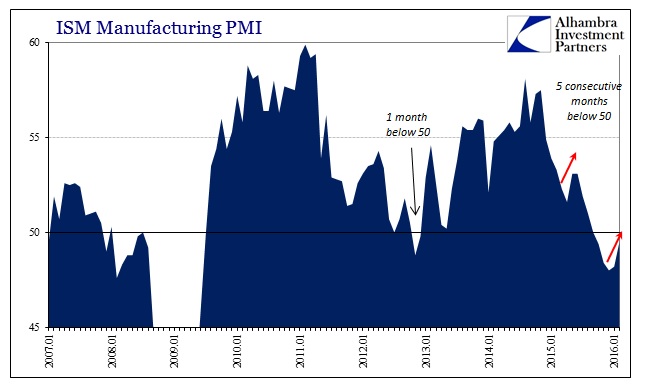

The ISM Manufacturing Index was reported at 49.5 for February 2016, up from 48.2 in January. It was the second consecutive rise for the overall index, December being the lowest, so the “it’s all over” narrative has been flying around heavily today. Lost in the relief is that February was the fifth consecutive month below 50 (and sixth straight at or below 50). It’s also a message and condition that we have seen before, notably last summer when the ISM’s PMI rose from a low of 51.6 in April to 53.1in May and June, closely followed by re-emphasis upon “transitory.”

In fact, there is always a tendency to over-interpret monthly variations. On July 1, 2008, the ISM reported its index peaked back above 50 in June 2008 for the first time after four months of sub-50 index levels. Like today, it alleviated some recession fears particularly in the sub-components. From Reuters on July 1, 2008:

Bond appetite eased in reaction to the unexpectedly strong growth components in the June ISM report, which also showed the prices paid index rose to an almost three-decade high, fanning fears of inflation that erode bond values.

“It’s negative for bonds and pro stocks. It paints a slow growth scenario with rising inflation. That’s a tough path for the Fed to traverse,” said George Adell, fixed income strategist at Commerce Capital Markets in Jupiter, Florida.

Even the original ISM press release overstated the economic case, as the recession had already begun but misreading economic accounts especially in isolation kept alive the idea that the worst of 2008 would be just a slowdown no matter how many markets and banks failed.

Economic activity in the manufacturing sector expanded in June following four months of contraction, while the overall economy grew for the 80th consecutive month, say the nation’s supply executives in the latest Manufacturing ISM Report On Business.

That was July 2008, not July 2007, where even after Bear Stearns recession was still believed just a small possibility by far too many. The ability to ignore context and to place so much faith in “stimulus” remains ubiquitous no matter how much “market turmoil” is presented. There was a similar response into the 1990 recession, where the ISM Manufacturing PMI had fallen below 50 in early 1989 but then rebounded back to 50 by April 1990 – just two months before the official “cycle peak.”

Even the Markit Manufacturing PMI, which has been noticeably higher than the ISM for the past year, has come back down into suggesting not just this “manufacturing recession” but that it is still far from over or yet at its worst.

U.S. factories are reporting the worst business conditions for over three years. Every indicator from the flash PMI survey, from output, order books and exports to employment, inventories and prices, is flashing a warning light about the health of the manufacturing economy.

Again, context matters, not just from China but the entire global “goods economy.”

World manufacturing sector growth stagnated in February as falling prices failed to stimulate new orders, pushing factories to trim workforces, and dealing a blow to policymakers who are struggling to stimulate their economies.

Manufacturing output across much of Asia shrank in February while waning throughout Europe and remaining sluggish in the U.S., according to surveys of purchasing managers on Tuesday…

“Inflows of new business and production volumes barely rose, while the trend in international trade deteriorated,” said David Hensley, a director at JPMorgan. “Market conditions will need to improve in the short run if global manufacturing is to avoid falling back into contraction.”

“If you were looking for evidence of manufacturing growth stabilising then this isn’t it. There were a couple of low spots that are quite surprising,” said Philip Shaw at Investec.

The point of these PMI’s is not whether above 50 or below 50, such precision is fallacy, rather it is that the world economy overall and local networks within it (such as the US and US consumers) are clearly under imbalanced conditions that present very real dangers. Whether or not that means recession is beside the point right now, as official declarations are a post hoc matter for historians. Imbalance is nasty business; to see it globally and in such a heavy and uniform way under rather and relatively benign conditions is quite alarming. Around the world there are as yet any systems expressing major job losses and still global manufacturing recession is suggested.

When the FOMC gathers soon to contemplate their monetary policy “communication” (not rate hikes, credit markets are having none of that) they will have to account for this contradiction. The US economy is in their view close to overheating yet this global manufacturing recession is the best case (that it will stay manufacturing). The dichotomy is such that those are mutually exclusive possibilities. Personally I don’t think that it makes any difference whether they raise rates or not, but it might again highlight their unique ability to only make a bad situation worse – even if all it ever amounts to is lost credibility. The economy appears yet again stuck in the “wrong” direction no matter what, meaning that the only variable might be whether or not at some point the economy (US and global) shows the “V.”

Stay In Touch