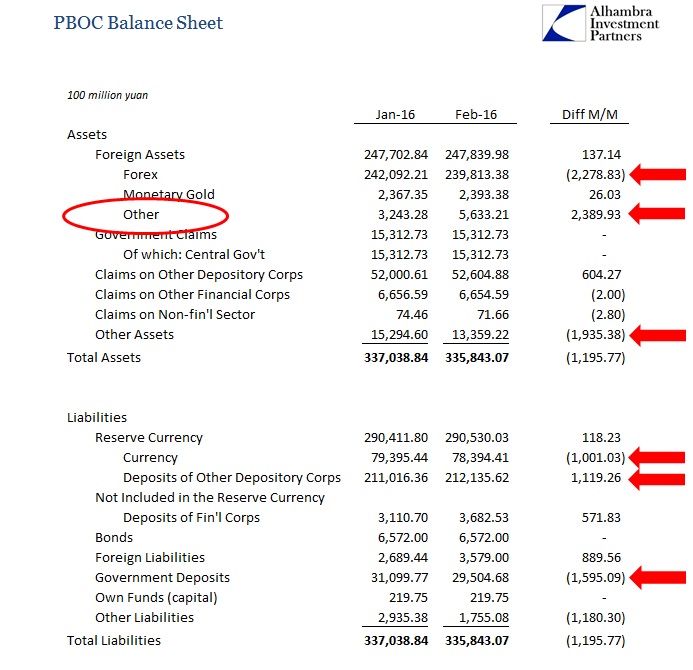

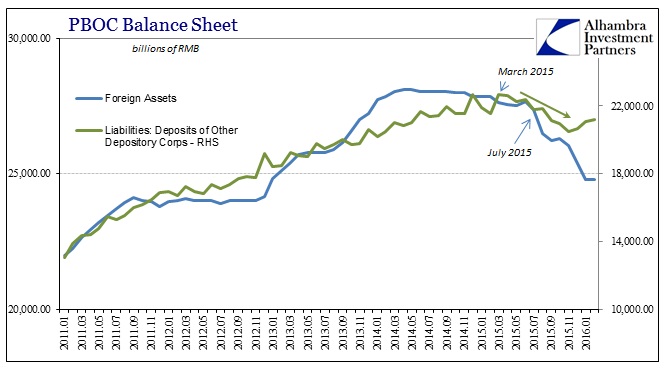

The PBOC’s balance sheet was relatively quiet in February, with no large moves on either side of its ledger. In fact, these minor shifts appeared to be more so adjustments than the more extreme efforts the central bank had become used to undertaking. The heavy lifting was accomplished in January at least as far was what is visible, leaving February’s statement seemingly unremarkable.

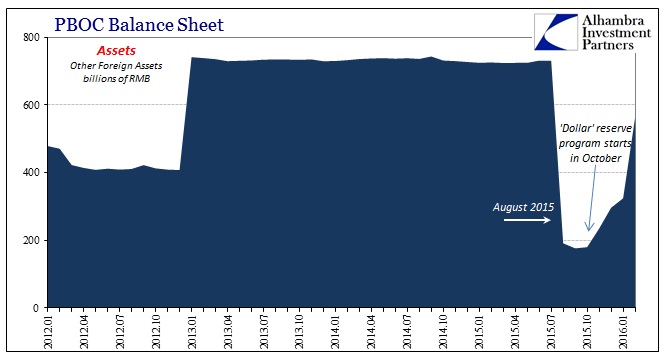

Total forex assets, the very base of the PBOC’s monetary existence, actually rose slightly February for the first time since October. This is not to say that the PBOC wasn’t still releasing its “dollar” base back into the system (“selling UST’s”), as the mainline of its forex assets declined by RMB 229 billion. That amount was offset by “other foreign assets” which includes the dollar reserve requirement imposed on October 15 on Chinese banks that allow their customers to “buy dollars.” In February, the increase in those balances, which amount to nothing more than a zero-interest, 1-year dollar loan to the PBOC, was slightly higher than the reported amount of forex declines.

That jump in February in “other foreign assets” was by far the largest since the requirement was imposed; nearly 9 times as large as the “flow” taken in January when conditions were far more intense. That suggests that whoever was “buying dollars” in February at least through official Chinese banking channels was doing so at a massive pace. From that we can infer, given the rough peg in CNY and SHIBOR, and now more calm in even offshore HIBOR (subscription required), that there was far more going on than it may have seemed from official statements and reports.

From the PBOC’s perspective, this reserve requirement is only refilling what looks to have been a “dollar” cushion that was used up right in August 2015. In other words, the Chinese central bank is using “dollar” demand through banks to fund at no cost its emergency ability to handle the next drastic “dollar” shortage.

I wrote back in October just a week before the dollar reserve became active:

In any situation where banks are funding “dollar” positions on a client’s behalf triggers this reserve; the transactions where the client is providing “dollars” to banks are not. Looking at that factor from the bland, orthodox perspective might lead to “curbing the yuan’s depreciation” as a reason for the peculiar arrangement here, while the wholesale view suggests a multi-layered tactic to suppress difficulties within China’s end of the global “dollar” short.

For one, it seems to have worked, at least for the month of September. While China still reported dollar outflows, -$43.26 billion, they were far less than anticipated and less than half of what was reported in the amazing “run” of August (-$93.9 billion). Predictably, that has led already to pronouncements that “it” is “over.”

Déjà vu in February 2016. China’s State Administration for Foreign Exchange (SAFE) reported a decline of only $28.6 billion last month after the hefty $99.5 billion in January that matched outward appearances. In other words, the pattern is holding just as it did from August to September and then October (which was actually reported as a positive forex “inflow”). The events of November, however, showed that there is much that is not reported or visible, only inferred. The dollar reserve is only one such factor.

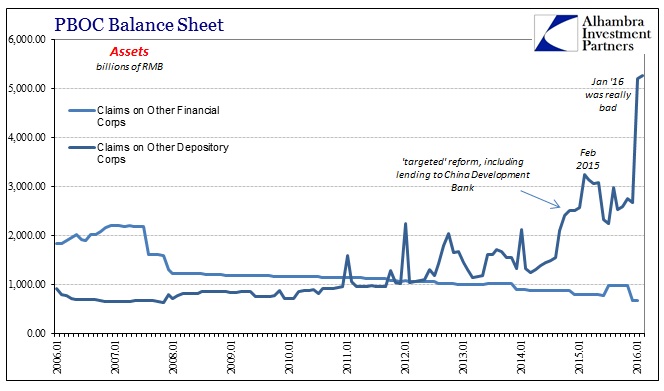

While the PBOC had been reluctant to expand its balance sheet elsewhere beyond its shrinking forex base, it was likely forced into abandoning that resistance by the severity of January’s monetary conditions. While mostly channeled through the SLF and MLF into narrow, state-owned conduits, it would be unwise to think that overall expansion did not have a broader effect. It was, however, not repeated in February as the PBOC only maintained those balances which will, at some point (depending on exactly which program was accessed) have to rollover in perpetuity or be allowed to expire (the SLF is only one- and seven-day funding arrangements; the MLF is six-month).

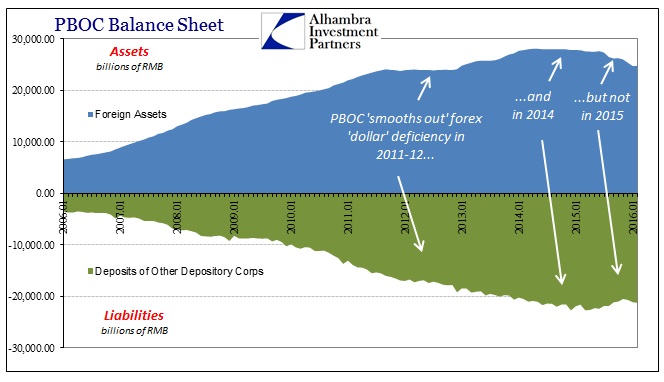

Chinese bank reserves have stabilized during the worst stretch in global liquidity. That suggests that the problem is outside the RMB system and that when “allowed” inside it creates a huge and unmanageable mess, putting the PBOC between the rock of the eurodollar decay and the hard place of having to monetize internal offsets. Starting January, it chose the latter and stepped up its efforts to contain as much as possible, leaving only the scale and tempo of the interventions to be sorted out.

That’s really the key to all of this, as the PBOC’s reach is far beyond its own balance sheet. In other words, what we see reported officially as “reserves” and assets are not nearly the full extent of the central bank’s mandate. It can demand Chinese commercial banks act on its behalf, especially in the case of managing external “dollar” pressures – that was the whole point of the reserve imposition to begin with.

“Sometimes it’s the commercial banks that sell a lot of dollars when the PBOC wants to prop up the yuan,” said Zhou Hao, a senior economist at Commerzbank AG in Singapore. When this happens, the slide in foreign-currency assets held by Chinese financial institutions “is typically much larger than the decline in foreign reserves,” he said.

If the PBOC is absent from supplying “dollars” (selling dollars) to the starved Chinese funding connection, then that doesn’t necessarily mean all is well. Overall Chinese bank holdings of foreign assets had been falling since, not coincidentally, August last year. Exactly what Chinese banks have been “selling” isn’t as well known, and now we may not know for some time as last month China made a change in reporting:

China’s central bank omitted details of financial institutions’ foreign-exchange holdings from monthly data that sheds light on the scale of its intervention to support the yuan.

It leaves open too many possibilities especially in February given the sudden burst in the dollar reserve requirement postings. Chinese banks reported an increase in foreign assets (net) in January, but that isn’t surprising given the immense official support. What we really want to know is what and by how much was all this other unofficial activity, including any “orders” placed on its behalf through Chinese banks. All those hidden transactions and balances are just the kind of maneuvers (wholesale swaps, forwards, repo, etc.) that will come due and re-exert significant “dollar” pressure at that point. It accomplishes only a short window of maturity transformation. What I wrote back in October seemingly applies again:

Which brings us all back to the question about what, exactly, is an “outflow.” If a flood of PBOC-generated swaps and forwards sets up only a maturity transformation moving the “dollar” pressure from August or September to October and November, then being effective means being able to either deliver “dollars” then (instead of September) without an October disruption, or going deeper into maturity transformations (a form of, as noted above, high cost future indebtedness) in order to continue fooling “markets” into thinking there is nothing going on at all by maintaining this same outward appearance of resumed stability. That latter is surely the motivation behind O/N SHIBOR’s sudden meaninglessness.

In my view, and this is speculative on my part but I don’t think unreasonably so, the October 15 reserve mandate seems to be a hedge on the PBOC’s “dollar” intentions as far as taking the first option so as to keep the process to as much of a minimum as possible.

We can infer from the vast and damaging CNY events starting in early November that the PBOC “spent” a great deal of effort in pushing its August maturity transformation all the way past October and into November – but there it was left to still deal with the reckoning upon unwinding, which, obviously, it could not. Instead, this time around, it appears very much like the PBOC has deployed many of the same external factors in likely increasing intensity now matched by more determined (though still relatively narrow) internal expansion (at least in January).

In short, the ratchet effect. The PBOC keeps repeating the same general tactics with each decay cycle, only with greater purpose and concentration at the next iteration (especially reviewing the China’s monetary history since the “rising dollar”). What doesn’t change is the cycle itself, especially since almost all of this massive intervention is aimed only at hiding it.

Stay In Touch