Throughout 2014 and even into 2015, the word “decoupling” was resurrected to try to calm growing unease about the direction of global growth. It’s first broad usage was during the first part of the Great Recession, as economists were sure that emerging markets then would be able to weather the “slowdown” of 2008 believed at that time confined to the US and Europe. It was an absurd suggestion but perfectly consistent with orthodox economics and its idea of closed systems.

When the word was brought back in 2014, it was under seemingly far more happy circumstances. China was acting curiously and places like Brazil were wrote off as if they had their own problems, maybe even big problems, but the US, Europe, and even Japan were supposed to be finally back on track. Again, the idea of closed systems propelled this “logic.” As I wrote in September 2014 under the headline China Profoundly Disagrees with FOMC Assessments:

That more than suggests not only a widespread slowdown, but also why Brazil and Australia are enthralled by recession. The larger question in a world obsessed by some ephemeral and eternally positive “global growth” construct (at least economists as they are in setting forward predictions about specific growth regimes) is how that Chinese slowdown fits within more unique circumstances about specific systems. When the first vestiges of Chinese production deceleration became apparent in early 2014, it seemed very curious to the mainstream because everything about “global growth” was headed in the “right direction.”

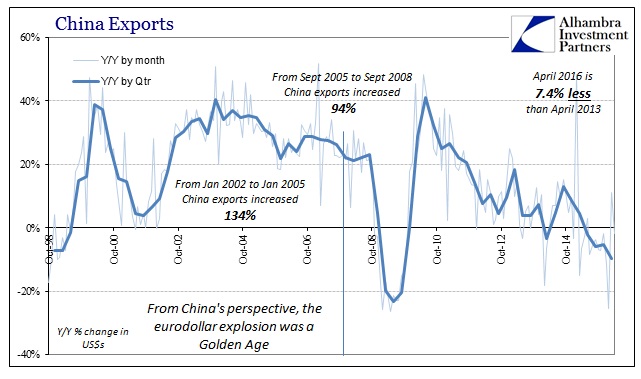

Since China’s economy was built to manufacture everything global growth could buy, it set up this major disagreement. How could industry in China be decelerating sharply and to lower and lower levels while economists saw only economic achievement for the US and the other developed markets? If economists were right particularly about the US, then they would have to explain why rapid US growth had suddenly forgotten to buy much from China.

They couldn’t, of course, which is what the word “decouple” was meant for, to simply wave China’s struggles away as if they were unimportant global components. Instead, “decouple” was as I wrote in 2014 applicable only to the FOMC and economists’ narrative about the US economy. Their views had departed from reality, as increasing Chinese misfortune was perfectly consistent with the underlying and intensifying US economic weakness obscured by whatever the BLS was producing as labor estimates.

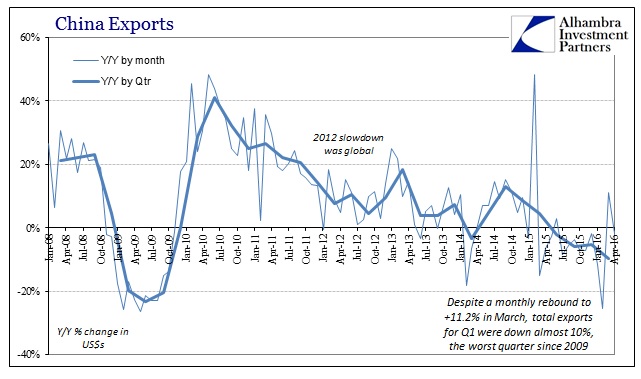

Chinese trade figures for April 2016 are once again spotlighting the disparity, perhaps more intensely than ever. After such a hopeful rebound in March, the current monthly estimates further show that it is only economists and the mainstream narrative that sees these things. Exports rose 11.2% in March (revised), the cause of much sustained enthusiasm, but that followed -11.5% in January and then -25.4% in February. For Q1 overall, exports dropped nearly 10% which was the worst quarter since Q3 2009. So where March’s positive figure was thought to be the final turnaround, seeing -1.8% and once more a negative number for April suggests for the nth time unearned optimism like that which gave us the second set of “decoupling.”

For the FOMC and the narrative surrounding the US economy, the Chinese trade update was much worse than even -1.8%. Exports to the United States fell 9.3% year-over-year in April, an enormous decline that doesn’t indicate anything good about the state of the US economy two months removed from January/February ugliness. Where economic slowing in 2014 may have been due to a broader “global” problem including the US, Chinese exports to its largest market may be indicating that the world’s slowing and contraction might now be due mostly to the US. The coming months will be important in determining that as a possibility.

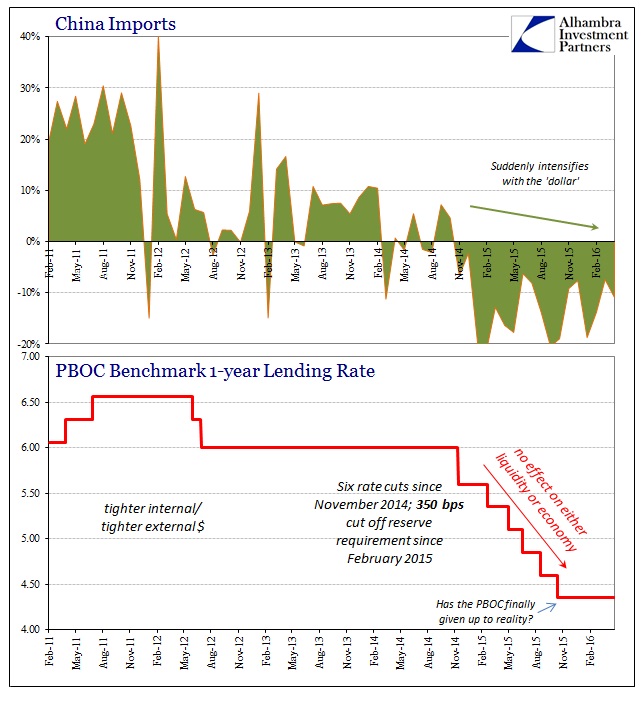

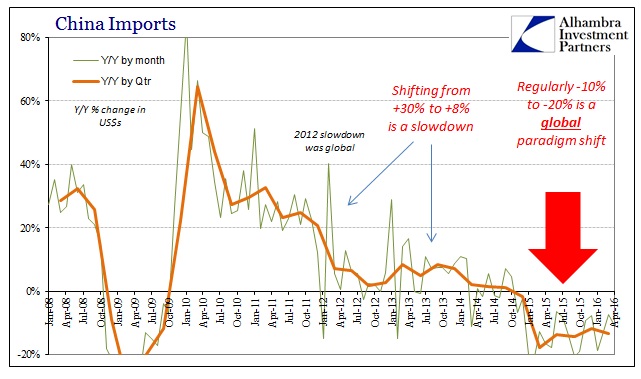

Because China’s industrial sector is awash in oversupply given these export levels, there is little demand from China to the rest of the world – the entire global economy is squeezed from top to bottom. Chinese imports fell almost 11% in April in contrast to what hope was extrapolated from a less negative import estimate in March. It shows that China’s external demand is frighteningly consistent, unmoved by either continual bursts of confidence or even PBOC “accommodation.”

That is what economists seem to be missing, as there is really no difference between -9% in exports or -2%; neither of those are +25% which is what the Chinese “need” to see in global trade terms. On the other side, the rest of the world had become expectant of robust Chinese exports inviting imports into China at 20-40% year after year. When China instead contracts in its inbound trade by consistently 10-20% it is both confirmation of the global economy as a singular deficiency and a likely very messy paradigm shift. Therefore, there isn’t any actual meaning in attempting to parse the monthly difference between -10% or -20% (or -7%) as they both signal the same thing.

Unless and until China’s trade levels find their way back to pre-crisis existence, there is only trouble ahead no matter the monthly variations. What we see in these estimates is global deconstruction which will only lead to more harmful distortion and continued negative factors.

According to a Wall Street Journal analysis of Chinese public companies, Chinese government support includes billions of dollars in cash assistance, subsidized electricity and other benefits to companies. Recipients include steelmakers, coal miners, solar-panel manufacturers, and other producers of other goods including copper and chemicals.

One beneficiary, Aluminum Corp. of China, or Chalco, said in October one of its units would shut down a roughly 500,000-ton-per-year smelter in the far-western Gansu region as it struggled to make profits. Executives prepped for thousands of layoffs.

Then Gansu officials slashed the plant’s electricity bill by 30%, employees say, and the factory was saved. Although a portion of capacity was taken offline, most is operational.

If there will ever be serious examination into why this downturn in “cycle” is so unusually elongated and historically inconsistent it would have to start with these kinds of “stimulus” measures. No slowdown in history has been fought tooth and nail quite like the one that began after 2011. It cannot possibly end in success, of course, that much should be fully apparent by now. The most it can accomplish is to keep the “V” shaped decline from occurring. In light of the cost of time, however, this slower, drawn-out downward slope is a much, much worse result.

Under the direction of orthodox economics (the fusion of Keynes and monetarism) the world’s “stimulus” apparatus is making a bad situation worse by (at best) dragging it out far longer than maybe it would have under more traditional business cycle conditions. They do so, of course, under the assumption that 2005 is still an available scenario and thus any weakness is a “temporary” deviation from the path returning there. Belief in the power of “stimulus” to make it happen prevents awareness of what is, again, really a paradigm shift that will not be altered. What we are analyzing, then, is not what awaits but how long it takes to get there and the huge, growing costs to delay what looks only inevitable.

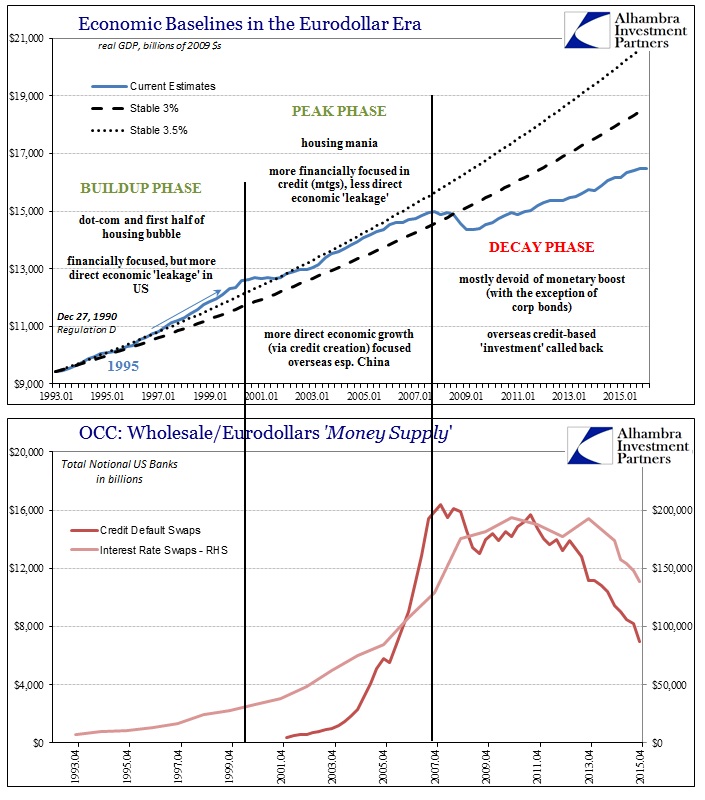

The very idea of systemic reset immediately conjures the worst kinds of associations. It is understandable because going through it is not pleasant and humans by nature seek to avoid unpleasantness even where the probability of doing so is small. In economic terms, really financial since this is all being driven by the eurodollar’s retreat, systemic reset is indeed ugly and violent but ultimately fruitful. The reason for that is really simple, because any system pushed to the point where reset appears as increasingly inevitable is a system that is badly imbalanced and malfunctioning. The reset is the answer, not the problem. Delaying the answer only elongates the pain of the problem.

The systemic problem is what the eurodollar’s rise represented – an open world of financialism where credit was unrestrained not just in terms of debt proportions but within the very idea of money itself. It was highly unstable and only delivered the appearance of prosperity for those most disturbed by it (including the US). Getting away from it is the world’s first task for actual recovery, but authorities proceed as if this was all just some minor inconvenience. The end of the eurodollar system should be cause for global celebration but it is not since there is nothing ready by which to replace it. Instead, it comes on anyway and leaves only greater strain and uncertainty about what it will mean and the world might look like at that point.

Stay In Touch