Despite the fact that the Fed has raised rates and therefore signaled via policy communication that their view of the economy is rather positive, both bond and stock prices don’t seem too caught up in the optimism no matter how much attention is paid to the shifting sands of monetary policy. Yesterday, the media was full of stories about how stock investors were nervous about the newfound respect for “hawkishness” at the FOMC; stocks dropped. Today, that was all gone, apparently, as stocks rose.

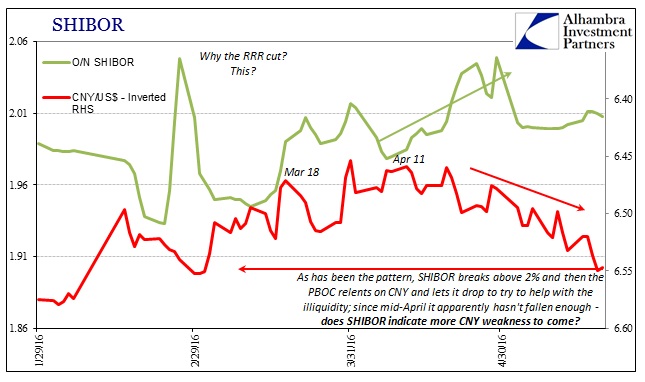

Both days, however, were more closely resembling of the CNY exchange rate. Yesterday, the PBOC fixed the reference rate to its lowest since the start of March; global stocks fell. Today, the PBOC fixed the middle of the exchange band moderately higher; US stocks rebound. It’s raised not just questions about US monetary policy, as I wondered yesterday, but perhaps more basic considerations like value, especially monetary value.

If the eurodollar system is itself the determining factor in all of this, both markets and economy, and I believe it is, then how do we “value” the eurodollar? It isn’t gold; it isn’t even a thing. By every account, the eurodollar is much different than a dollar yet it is and has been treated as a dollar at the same rate – in most times. That is why the panic in 2008 remains an almost fixed reference point, because at those moments of the most intense pressure we got to see that there is, in fact, a difference. It was almost like particle collisions in the most powerful accelerators; to actually measure the most fundamental building blocks of the universe requires the briefest bursts of the most intense energy imaginable in order to pull apart the seemingly seamless fabric of space and time.

There can be no doubt that the eurodollar is not the dollar. Conceptually they are radically different but up until August 2007 there was no evidence they were ever treated that way. Then, suddenly under intense scrutiny, federal funds rates radically diverged from LIBOR. There was always a difference or premium, but that was easily found via time value; this was fundamental difference, especially since LIBOR surged while federal funds traded a whole lot less than the FOMC’s target (including at times in spefici trades 0.00%). In the purest sense, it was brief recognition (twice) that the eurodollar should not itself be acceptable at par with the domestic dollar.

From that sudden emphasis, it might stand to reason that the ongoing breakup in the eurodollar system might be due to it. If there really is a difference between dollar and “dollar” then Gresham’s Law should apply; or, more appropriately, maybe its inverse in Thier’s Law. The latter “rule” takes Gresham’s Law only with further consideration of legal tender. In other words, if private economic agents are given a choice of competing monetary formats they will conduct trade with what they believe is the highest quality or best long-term value in money. If they are instead required by law not to discriminate, they will keep “good” money and use or circulate the “bad” forms.

It is a difficult conception to apply in these eurodollar circumstances because there is actually no legal tender applicable. Furthermore, there are no eurodollars; the eurodollar is not a thing like the dollar is a thing. The eurodollar is a system that is more than the sum of its parts. I like to compare it to the internet because I think that is the best, most intuitive analogy. The internet is not the sum of individual internets, it is the combination of hardware and software (protocols) spread all over the world that allows various and very different systems to combine in order to deliver the speedy and reliable flow of information.

Because the eurodollar system straddles this kind of arrangement while also remaining as a monetary system in its final expression, it leads to misunderstanding even of terminology. When I speak or write of a “dollar shortage” my use of the quotation marks is intentional. I am not referring specifically to a literal shortage of things, like if there were not enough physical dollar bills in global circulation (though, right on cue to add to the confusion, that does seem to be a quite related manifestation of the primary “dollar shortage”). In other words, if a power outage knocked out a significant portion of the telecom network you would not refer to it as a shortage of internet; it is more correctly identified as a reduction in systemic capacity that leads to communication disruption.

So it is with the eurodollar, as the “dollar shortage” refers to reductions in general capacity; the idea of “dollar shortage” is attached as easily understandable shorthand for what to expect under these kinds of circumstances (commodity crash, deflation, depression, etc.). That is because the eurodollar system is, like the internet, a combination of really standards and protocols that are enforced via the determined effort of global banks and their balance sheets (not central banks and theirs). Stability, or the appearance of it, is the combination of all those in “necessary” capacity as determined by internal conditions. Eurdollar instability ends up with monetary disruption.

Relative changes in prices due to that disruption is rather easy to conceive and consider; what I believe also demands deliberation is any potential change in “value.” Might the practical application of Thier’s Law explain, for instance, the paradigm shift in hoarding of sovereign debt? In other words, while the eurodollar’s ultimate expression continues to function as money, the interbank markets are not obliged to make a singular statement or effort as to how that happens. Therefore, they might be “valuing” individual monetary components separately in contrast to a uniformity that existed pre-crisis where the individual parts of the individual eurodollar protocols were accepted as indistinguishable in value and more aligned as to function (this is another instance where the English language, or my own grasp of language itself, is an impediment to communicating pure abstraction).

It might also apply to the continuous and tremendous reduction in derivatives capacity, at least as defined as gross notional exposures. As a separate piece of the eurodollar system, credit default swaps no longer carry the same “par” value that they once did before the panic required re-evaluation of them. Before 2008, AIG (or any of the monoline insurers) could issue CDS freely and openly but as the events of 2008 progressed the firm’s offerings weren’t nearly as accepted as they once were. The monetary analogy would be a bi-metallic standard where legal tender was not in force. As Thier’s Law suggests, under that condition where, say, silver was suddenly taken as overvalued, counterparties would increasingly only accept gold in payment or still silver but only at a large premium. In systemic terms, that situation is and actually was a huge monetary disruption of “money supply” (interbank) at that moment of freely determined revaluation. The longer it continues in that condition, the more monetary restraint acts upon the economic system and further erodes the usefulness (and profit) of silver itself.

In 2008 eurodollar terms, the ultimate payment function of all this money is not goods and services in the real economy but instead among interbank counterparties that solve into bank assets and corresponding liabilities that then allow actual economic agents to buy goods and services – just to add another level of complexity, further distancing abstraction from intuitive understanding. It is literally derivative, or money of money. To be as clear and simple as maybe I can possibly be, the eurodollar is thought to be what ends up on the asset side of a bank balance sheet like a loan that someone somewhere in the real world uses as money, but the eurodollar system is really more about all the parts that go into getting it there including those that don’t show up on any balance sheet or do so in only partial fashion. Contraction in money of money leads eventually to contraction of just money, and then just contraction.

I realize and admit that this discussion probably does not help clear up all that much as far as misconception and misunderstanding, but I still think it worth the effort to try to consider a more comprehensive reasoning of the eurodollar’s ongoing demise. It’s not enough to simply believe that the clear monetary regime change started on August 9, 2007, is due to “too much debt” or even the lack of further geometric progression for eurodollar banking. Had the eurodollar system not been interrupted, it is very likely that “too much debt” would not now be an impediment (to itself; to common sense is another topic altogether) as exponential expansion went on and on.

The implications of this difference are enormous, which is the point of this effort; if the eurdollar ended because of “too much debt” then it could easily be restarted by mimicking the processes of the eurodollar. In other words, a monetarist solution in the form of monetarism just updated. If there is truly value here, then like entropy there really is no going back. As far as abstractions go, entropy also seems an appropriately comparable concept to the eurodollar system.

There has to have been “something” that stopped it dead and caused this irrevocable reconsideration. Even though the eurodollar is not strictly speaking truly money, it is very likely that “value” played a primary role in that systemic break. The dollar itself has no intrinsic value, but what might that say about money of money? How might banks act differently if they start to appreciate the difference, being tasked (by themselves) to hold money of money in order to deliver useful forms of money for the real economy? The eurodollar was really a qualitative expansion that led to all the quantitative bubbliness because nobody questioned what was just accepted behind it all (like subprime mortgage collateral that was once accepted at par, meaning low repo haircuts). As long as all the internal numbers balanced nobody, it seems, wanted to know why they balanced.

It stands to reason that if this is even close to a correct interpretation, then it might explain why certain parts of the eurodollar system have behaved as they have – often at the expense of other parts because banks have been forced into asking those questions. Hoarding collateral makes for not just difficult repo but again derivatives that depend as much on it. It would be the epitome of the instability of the “rising dollar.” It seems to go up in value but only because the separate systemic pieces (protocols or whatever) are being revalued and not favorably, leading one to wonder exactly which dollar or part of dollar (eurodollar) is rising? Any such system so set against itself cannot last.

It is in many ways a fitting end, or at least the likely contours of its terminus. The eurodollar itself replaced gold in a fit of forced legal tender where the world’s monetary authorities in ending the gold standard (in practice it was a long and drawn out process) affixed this eurodollar “par” to begin with. As that marked a systemic reset, so too does this line of inquiry suggest a similar if opposite bookend.

Stay In Touch