It makes for yet another huge dichotomy, but one which is curiously absent from any mainstream commentary. As noted earlier today, Chinese imports were pleasantly surprising for the mainstream as they were just about flat year-over-year. The fact that oil imports surged by nearly 40% seemed only to confirm that whatever might be happening on the export side (another dichotomy left unexplained) at least Chinese internal “stimulus” might be finally paying off. It is entirely wishful thinking.

Estimated oil demand in China has actually declined recently according to UPI (via ZeroHedge):

Oil demand in China, a leading global economy, contracted for the third straight month in part because of economic slowdown, data analysis found…

Analysis from S&P Global Platts finds China’s apparent oil demand, a measure of domestic production plus net imports, shrank 1.3 percent year-on-year in April.

“China’s oil demand growth is expected to moderate significantly in 2016 as gross domestic product growth slows on the back of economic rebalancing,” the emailed report found.

Despite the indication of further economic slowing, there is no doubt that oil is entering China at a rapid, rabid pace; so much so that right now there isn’t enough room to offload all the tankers at the vital port of Qingdao.

Oil imports by China, the world’s biggest consumer after the U.S., fell to a four-month low as congestion at one of its biggest ports curbed purchases from independent refiners…

While imports slipped on a monthly basis, inbound shipments in the first five months of the year have surged 16.5 percent over the same period in 2015, according to customs data.

It’s a contradiction that demands explanation, but since it appears favorable to the mainstream narrative it won’t ever get one. There isn’t any mystery here, however, as the answer is readily apparent – China has an external financing problem. The reappearance of Hong Kong over-invoicing suggesting “capital outflows” occur as updated Chinese figures show once again the “unexpected” reappearance of official sector “selling UST’s.”

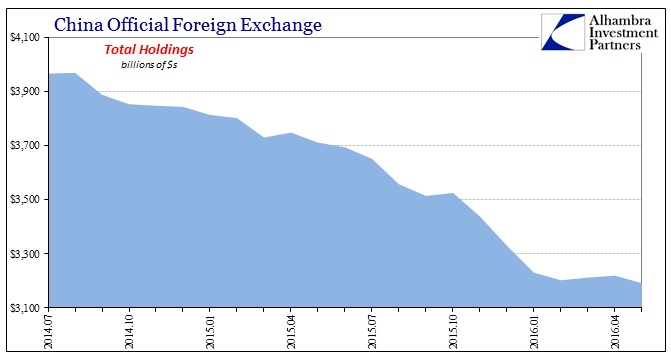

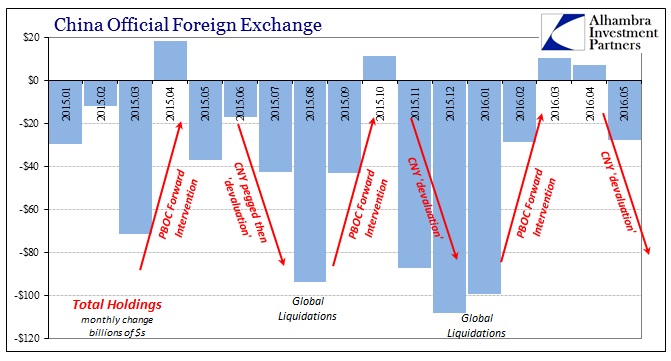

Total forex assets according to SAFE fell by almost $28 billion again in May after two months of small increases. When China’s forex change turned positive in March, that was extrapolated into “currency stability” also of the monetary policy and “stimulus” variety. Instead, it was easily observed as nothing other than duplication related to the maturity transformation of wholesale, forward “dollar” cover written (and then un-written) by the PBOC.

First and foremost, there is absolutely no awareness that this is simple repetition – and almost exact repetition at that. It’s not enough to realize that we have seen this before, but the last three months are an almost exact replay of August-September-October.

That is exactly what we find now two months later as both CNY and China’s “reserves” are once again declining in synchronized fashion – exactly as this pattern has had it for what looks like a fourth time. The only difference is so far the degree and the delay; the PBOC managed a second monthly increase in April in addition to March compared to just October the last time (and just April 2015 the time before that).

Absent an actually stable currency regime, meaning external funding via “dollars”, the importation of oil makes perfect sense wholly unrelated to demand for it. It allows the Chinese to essentially convert their own “dollar short” into a liquid (in the “dollar” sense) commodity, thus transferring some (large) margin of their financing issue elsewhere in the world (mostly Africa that I can determine). Though updated financing figures for May will not be released until next week, the TSF estimates through April 2016 are a more than sufficient demonstration:

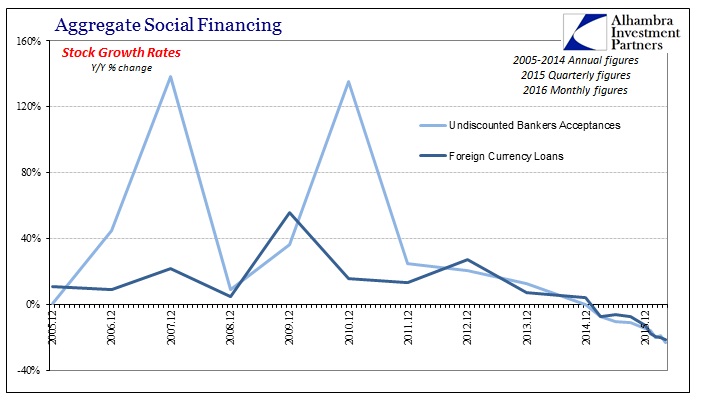

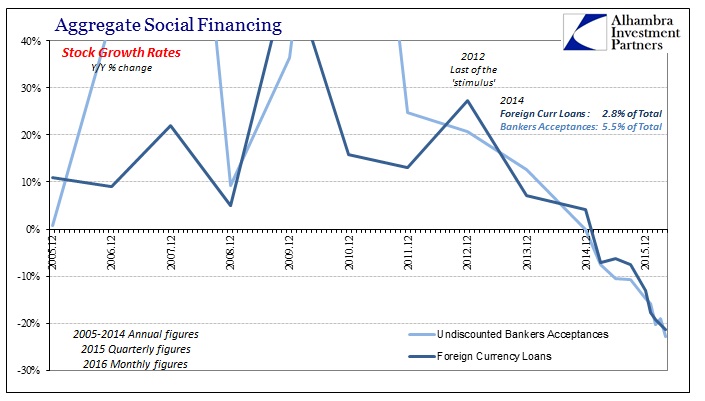

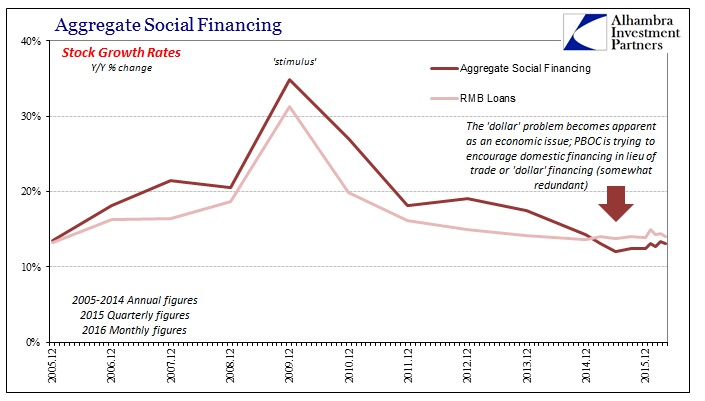

The loss of “dollar” financing (though it should be pointed out the external flows are not exclusively denominated in dollars) continues and continues to be quite severe. In April 2016, the PBOC reports that foreign currency loans contracted by 21.3% Y/Y, worse than the -20.2%, -19.3%, and -17.8% in March, February, and January respectively (and compared to just -13% in Q4 2015). In Bankers’ Acceptances, the magnitude and trend is the same. As noted previously, the PBOC is attempting to offset this decline in external financing by “allowing” some additional internal credit expansion (but nowhere near what it was like in either 2009 or 2012).

Part of the reason for that is that these are not perfect substitutes or even really close substitutes. The PBOC can only offer “dollars” in limited circumstances via forward injections as enticements for Chinese banks to further import them without any guarantee that they will be further used to finance China trade (PBOC forward cover is not at all the same as increasing the potential level of acceptances). On the internal side, an increase in China’s corporate bond issuance in RMB does not directly impact overall Chinese “demand” especially if China’s corporate sector is using corporate bonds in lieu of past lending commitment rollovers in anticipation of further illiquidity and disruption (which is exactly what US corporates did starting in 2009).

So the Chinese import massive amounts of oil not because a recovery is gaining strength but rather due to the financing squeeze (“dollars”, “dollars”, “dollars”) continuing to get worse. And even then the mainstream continues to suggest and classify all this as “capital outflows.” It is pure monetary contraction, wherein the virtual currency of the eurodollar system can and does just disappear into nothing. That leaves central banks trying to handle this deficiency as best as they might (given their serious handicap of an orthodox perspective) and accomplishing little other than, again, maturity transformation. And so this financial decay proceeds not all at once, but in waves, forcing adjustments along the way including massive quantities of inbound oil.

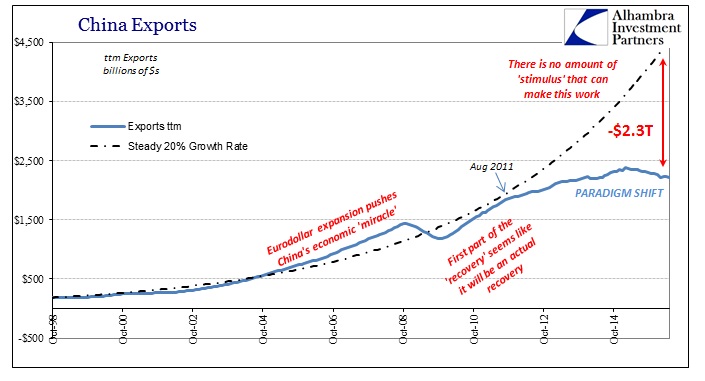

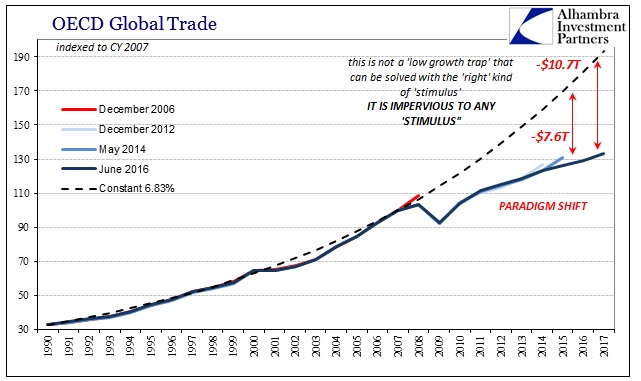

It continues because the PBOC, or any central bank including the Federal Reserve, cannot “print” eurodollars. The only matter for global monetary expansion is bank balance sheet factors; you might suggest some indirect influence from monetary policy in whatever jurisdiction, but since June 2014 (and really late 2011) the cumulative, aggregate circumstance of the eurodollar balance sheet has been unresponsive if not impervious to all manner and quantities of “stimulus.” The primary reason is economy, or lack of it. Neither China nor the rest of the world is growing, and what growth there might be (positive numbers) is nowhere near the baseline levels of the pre-crisis age (the eurodollar’s “golden” age). That huge and exponentially growing gap has direct economic effects but also financial; without the possibility of reaching the pre-crisis economic baseline there is no good reason to take the financial risk of further eurodollar money-dealing. That retreat is, as you would expect, uneven, hitting first those economies most visibly distressed and thus financially vulnerable (Brazil in addition to China).

In many ways economists and the media are predisposed to see expansion and recovery in anything that is not directly and obviously recession. In this case, however, the difference is categorical and not densely so. Right at the start, the mainstream narrative should be forced to confront the Chinese importing huge amounts of oil that they don’t need. From there, there is no more “unexpected” economic weakness or regular flashes of currency instability – just imperfect and blunt responses to primal forces far beyond any control.

Stay In Touch