With auto sales coming in exceptionally weak in the retail sales report today and given the importance of the auto sector in an otherwise awful economy, it makes sense to go further in detail to try to tease out corroboration. The Bureau of Economic Analysis provides a wealth of supplementary data on motor vehicles that it uses to construct GDP. It gives us a breakdown across vehicle segments, as well as domestic vs. imports.

Since the dollar figures prominently in everything over the past two years, we should be able to find a couple of expected effects related to its “rise.” The first is any oil price follow-through, as consumers should have been further attracted via the advertised savings in gasoline. The second is the traditional idea of the import effect via the “strong” dollar. In other words, as the exchange rate rises, absent any changes in overall demand, the mix of US auto sales should distinctly favor imports.

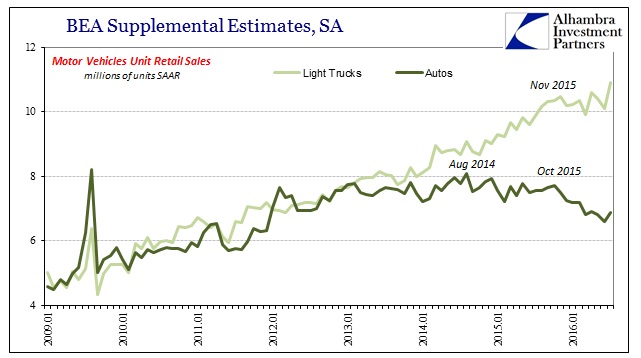

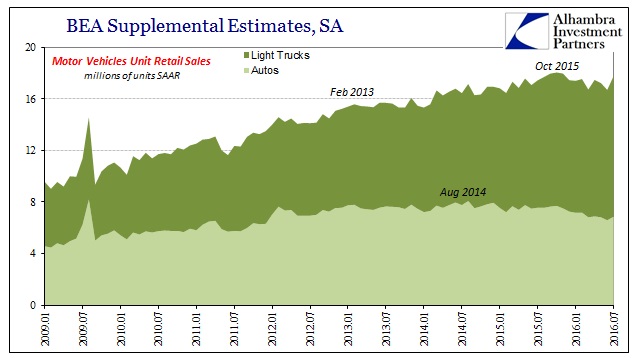

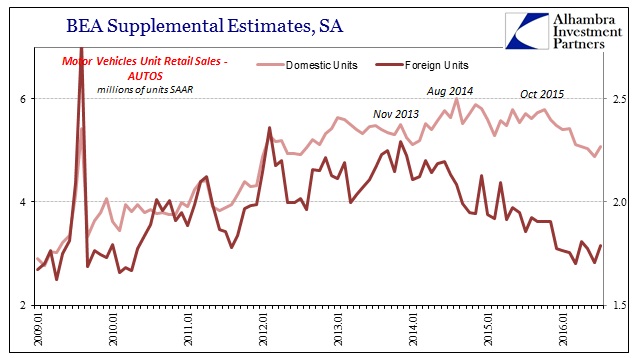

There is evidence for both of those within the BEA figures, but only in narrow circumstances. As to the first, sales of automobiles have been declining since August 2014 in favor of light trucks. That might be due to gasoline prices, although it may also be an income effect as trucks are typically more expensive, on average, than passenger cars. This level of analysis, however, only gives us unit figures which are a companion to the retail sales numbers from earlier.

The mix of sales did diverge well before the “rising dollar” period, so it is possible that growing employment or overall income may be attributed the changing proportion. However, that might also be the case in reverse after last summer, particularly starting October 2015 when auto sales fell off sharply while light truck sales notably paused. Not only that, as auto sales began to slow around the start of 2013, the pace of light truck sales simply remained steady – it did not indicate shifting preferences, only that consumers who were buying autos at the margins stopped doing so rather than switching to trucks. Those who were buying light trucks continued on at least until last autumn.

What we find, then, in unit sales is an overall slowing starting in early 2013 where demand for light trucks was not enough of an offset to slowing and then contracting car sales. Thus, gasoline prices may have been a factor in keeping truck sales steady for a time while auto sales fell, but overall there is no indication that consumers have taken oil prices positively.

That somewhat matches what we find in the retail sales version of MV sales, especially in 2016 as sales of both light trucks and autos “pause” while in dollar terms sales are now flat.

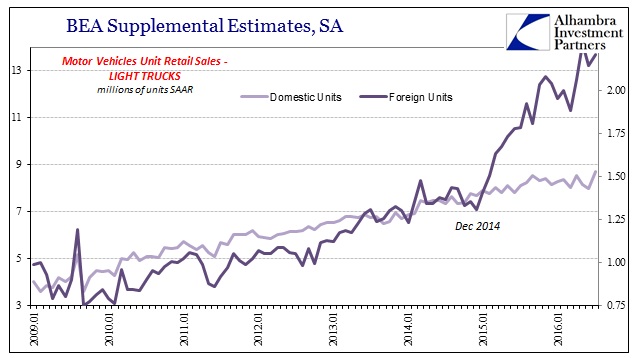

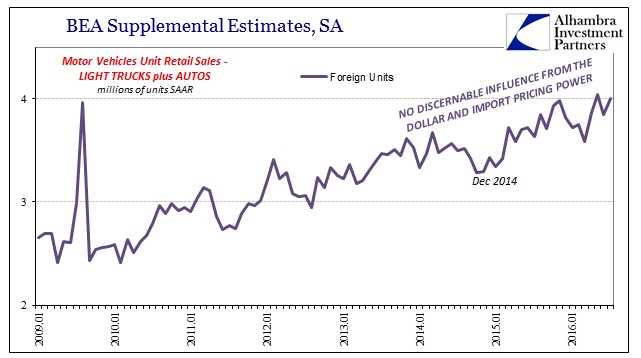

The “strong dollar” element to imports shows up in the light truck segment as a clear and oversized boost to truck units.

In December 2014, foreign light trucks were 14.5% of light truck sales, jumping to 20% by December 2015 and still more than 20% as of July 2016. But, as with overall vehicle sales, that positive impact of the dollar exchange rate disappears when factoring autos. Sales of imported autos have fallen sharply even more so than sales of domestic autos. Thus, there isn’t any “extra” demand for imported motor vehicles being indicated; only a shift from autos to light trucks (a serious boon for only truck buyers, both gasoline and dollar exchange in favor of imported trucks?).

Added together, imported motor vehicles were about 22.8% of the total retail for light vehicles (both autos and trucks) at the end of 2013 and still 22.5% in July 2016. In other words, there doesn’t appear to be an overall dollar effect for imports and a general benefit to US consumers; at most it is altering the competitive pricing environment for light trucks, but not enough to make up for lost share in (shrinking) autos.

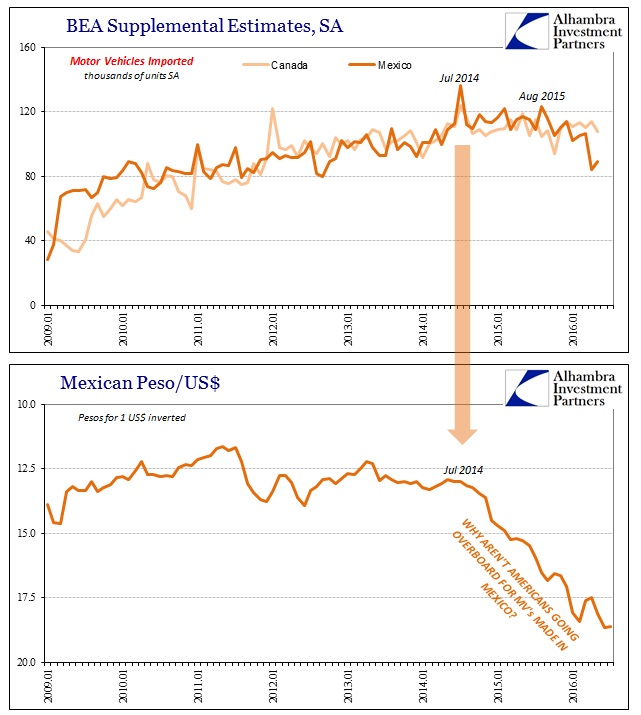

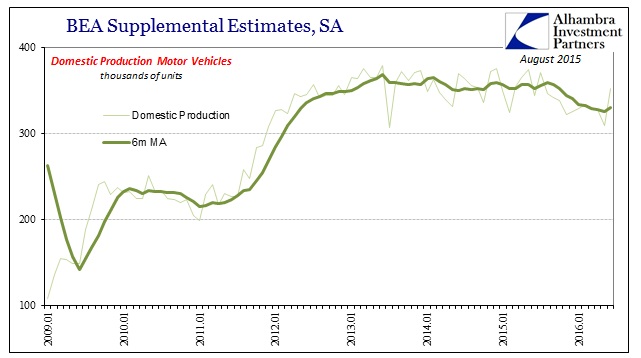

That doesn’t mean, however, that there was no effect from the dollar in the data. Instead, it is the “dollar” that is likely responsible for what we find in terms of some foreign production (importation rather than sales). Adding autos and light trucks together, the BEA estimates show falling imports from both Canada and especially Mexico. It is perhaps unexpected given the behavior of the peso in particular under the “rising dollar” condition. A much cheaper Mexican currency should provide at least enough of a boost to more than maintain a steady pace in import growth from south of the border; instead, Mexican imports have fallen and rather sharply.

The timing of the dropoff is significant, reflecting almost certainly eurodollar financing issues given “dollar” perceptions of Mexico (as an oil state first and foremost) as well as the change in domestic US demand (for autos and otherwise). Canadian imports have declined though far more gently in roughly the same time period, thus perhaps more in line with US demand than of funding difficulties.

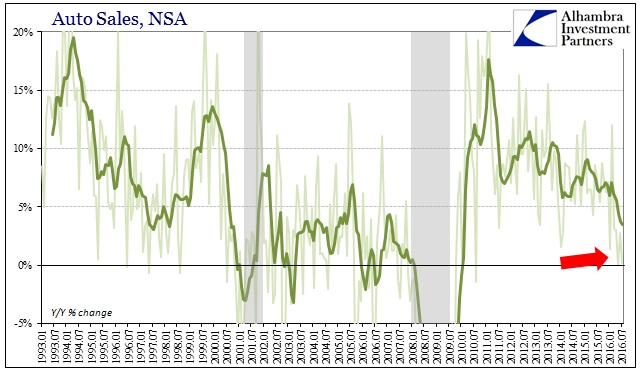

Therefore I think this data useful in limited fashion for dispelling a few orthodox myths about the dollar exchange, while at the same time offering some corroboration about the “dollar” economy. As overall retail sales, we don’t find evidence that either gasoline prices or the “best jobs market in decades” has created conditions where consumer spending on autos would significantly increase; just the opposite, particularly this year. It also leaves an open question as to why automobile sales have been so unusually weak for some time now (suggesting somewhat, in my view, the 2012 slowdown mechanics).

In terms of funding and currency, rather than seeing an overall benefit to US consumers via the higher dollar exchange, we find that limited to just light trucks and again not enough to offset lower proportions of imported cars. Instead, there is some evidence, particularly via imports from Mexico, that “dollar” as a mode of finance may be having further negative effects on overseas production that otherwise should be moving in this direction. There was 2-day strike at a particular Nissan plant in Mexico, but otherwise I didn’t find any event or factor that would offer an explanation for a 28% drop in imports from that country in less than a year (starting last August).

It is the general outline and contour of what might have changed for the global economy last summer in area of it that has been of outsized proportions during the stagnation of the past four or five years. It starts with a noticeable if not yet severe decline in US demand at the same time as the appearance of what might be very serious “dollar” funding irregularities seemingly directed more toward oil-heavy production states (perceptions of risk) or EM’s in general. It contradicts the orthodox expectations of greater US demand as both a boost from oil prices and the competitiveness of the import exchange rate as the primary currency consideration.

Stay In Touch