In April 2009, the new Obama administration created somewhat of a political controversy when it was originally reported by the Wall Street Journal that the US was providing $2 billion or more to fund offshore drilling – in Brazil. To many on the “right”, that seemed quite hypocritical given the public stance on all things oil. My interest is entirely apolitical, unseemly as it all is from any side, so it goes without saying that the original report was blown out of proportion for all the wrong reasons (as usual).

What was actually offered was the potential for $2 billion in either direct loans or loan guarantees provided by the Export-Import Bank of the United States to Brazilian oil company Petrobras. The timing of the negotiation, however, was the real story – the worst global currency crisis since the Great Depression. The world was short “dollars” and thus short of “dollars” at that particular moment, a big problem for countries like Brazil that depend on their export sector, and thus “dollar” financing, for economic sustenance.

Despite what might seem political largesse, Petrobras never touched a nickel. In early February 2010, the furthest, it seems, negotiations ever progressed was an offer of $308 million to buy goods or services from a US company funded by a loan from JP Morgan and guaranteed by the ExIm bank. No legal documents, that I can find, were ever signed and the offer simply remained nothing more than that.

By that time, Petrobras and Brazil had found alternatives, including the “dollar” market’s partial restoration. The oil company had discovered what looked(s) like an enormous offshore crude oil find, enough such that the deepwater field could be its own collateral under the right terms. Who finally offered them? Surprising no one, the Chinese.

Two months after the overdone drama in the US, in June 2009 Petrobras obtained a $10 billion bilateral credit line from China Development Bank. The final agreements were signed that November and called for immediate shipments of 150,000 barrels of oil per day to Unipec Asia, one of SOE Sinopec’s operational subsidiaries, increasing to 200,000 barrels per day starting the second year, upon the first withdrawal from the credit line. Petrobras’ CFO Almir Barbassa said at the time, “This funding is relevant not only due to the amounts involved, but also because it represents a new phase of relationship between developing countries.”

Indeed, that was absolutely true as both Brazil and China have been exchanging these kinds of funding commitments quite regularly in the years since the original deal. In 2010, Sinopec paid $7.1 billion for a 40% stake in Repsol-YPF of Brazil, and in 2011 it purchased a 30% share of GALP Brazil (a Portuguese company) when CEO Manuel Ferreira de Oliveira told Bloomberg News, “The $5.2 billion cash-in we will get from Sinopec is paramount for our strategy in Brazil.”

Last year, as Brazil’s problems began to be fully exposed, particularly on its “dollar” short, China Development Bank agreed to a further $3.5 billion in additional credit last May, signing another “cooperation agreement” with Petrobras including an added $1.5 billion disbursement with undisclosed terms.

And it hasn’t been just the oil sector. Also last year, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China agreed to provide Brazilian mining giant Vale with $4 billion in loans the bank would further syndicate, while the Export-Import Bank of China, China Ocean Shipping Company, and China Merchants Group all signed Memorandums of Understanding on terms of additional financing over a three-year period. The Ex-Im Bank would provide “dollar” financing to the shipping companies in order to transport Vale’s iron ore to China.

You might get the sense that Brazil is dependent upon China for funding perhaps even more than as a market for its resources. If China were ever to run into its own “dollar” problem, what might happen in Brazil?

Brazil’s biggest corporations, already reeling from a growing political crisis and the worst recession in a century, face a new threat: International banks have either stopped lending to them entirely or are demanding dollar-denominated collateral, people with direct knowledge of the matter said.

Not a single syndicated loan has been made to a Brazilian company this year, compared with $12 billion in 2015, and none of the nation’s banks or corporations have sold bonds without dollar guarantees since July, data compiled by Bloomberg show. More creditors decided to shun Brazil in the past 60 days after the nation lost its last investment-grade rating in February, the people said, asking not to be identified discussing private financing negotiations.

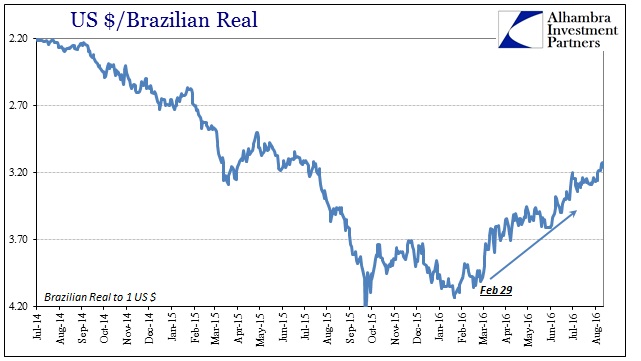

That Bloomberg article was written on April 1, 2016, about a month after the Brazilian real had reached its last devaluation stop. February 29 was the last day (so far) that Brazil’s currency traded below 4 to the dollar. Beginning with March, the real has rebounded somewhat, indicating at least the potential for stability that might further loosen private market “dollar” lending to the beleaguered domestic financial system.

Thus, it is not likely coincidence that on February 26, Petrobras was securing another $10 billion from China Development Bank. It was a déjà vu to 2009.

“The company is notorious for urgently needing more money, and everybody had already mentioned that getting money from China was its best option,” said Pablo Spyer, a Sao Paulo-based operational director at Mirae Asset Wealth Management. “This money will provide good relief.”

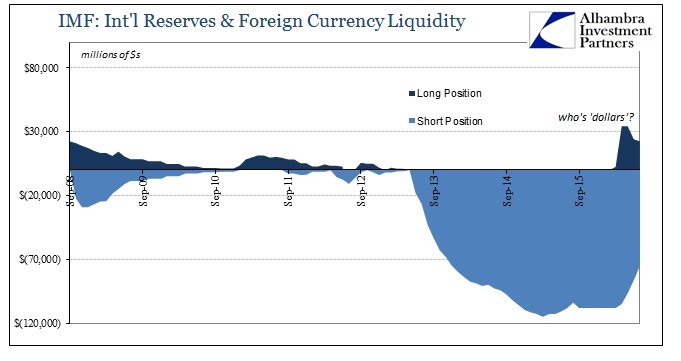

It raises even more interesting questions and prospects, too. Starting in March 2016, Banco do Brasil’s prepared call sheet for IMF reserve accounting shows the sudden appearance of a net long position in “financial instruments denominated in foreign currency and settled by other means (domestic currency).” The initial amount was small but provocative, particularly the timing with both Petrobras’ infusion and the real’s reversal. That part of the IMF call sheet had been notable before since that was where all Banco’s prior “swaps” had been assigned, only on the short side.

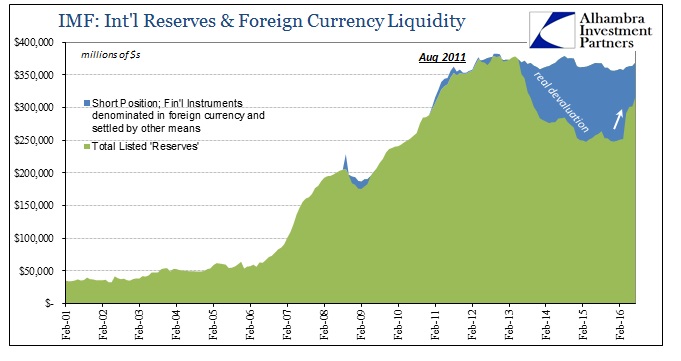

Thus, for March 2016, there was $108.1 billion short now offset slightly by $2.5 billion long, for a total net short of $105.6 billion. Given that Brazil’s total reported “reserves” (quotation marks intended given that these are wholesale financial pieces we are dealing with) amounted to $357 billion, being short some $110 billion in uncertain derivatives as well as the fact that those derivatives were ineffective in arresting real devaluation, you can appreciate quite well why the eurodollar market started asking Brazilian companies desperate for “dollars” to post dollar collateral or get nothing.

That indicated a great deal of pressure on Brazil, and really the rest of the official central bank world, to get ahold of the real, starting by reassuring the “dollar” markets that the country would have enough reserves to weather even severe recession. In April 2016, Banco reported to the IMF a major increase in its long position, this time a total $34.3 billion – an enormous sum especially in just one month. On the flipside, Banco had let expire about $3 billion in its short swaps, meaning that the net short was reduced massively to just $70 billion.

I have no idea where that position came from; no information on any counterparty providing what amounts to huge “dollar” cover, settled in reals. Could it have been the Chinese again, perhaps even the PBOC? I can’t rule it out, but I also can’t rule out anybody (except perhaps the American government and especially the immovably clueless Federal Reserve whose official policy remains to this day “what dollar problem?”).

Whoever it was, it appears to have worked; at least for the short run until now. For the month of May, the long position rose a bit more, to $34.3 billion, while Banco really started letting down the short side – declining to $96.4 billion and therefore a total net short position of $62.1 billion, the lowest September 2013 not long after the failed swap “rescue” began. As of the latest IMF report for the month of July, both the long and short sides are being reduced, as whatever cover and (maybe just funding credibility) was given again seemed to be enough. In the two months since May, Banco reports $12 billion less on the long side but $21 billion less on the short side.

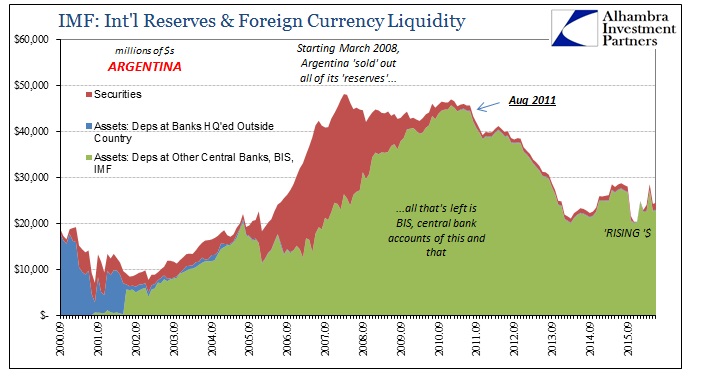

It is also interesting that one of Brazil’s neighbors, Argentina, shows somewhat similar effects of somewhat similar processes. I don’t want to make too much of the comparison, starting with the very different conditions in Argentina versus Brazil, but the correlations are worthy at least of notice and consideration. Like Brazil, Argentina has a “dollar” problem and one much bigger in proportion. The country had been forced by the eurodollar panic in 2008 to start selling off its reserve positions, leaving it by 2011 with nothing more than balances at the BIS and other central bank credits.

Then, just like Brazil, in August 2011 (a month that will show up in anything related to the “dollar”) even those reserves were forced to be mobilized. By the end of last year, total reported forex were just above $25 billion. The new incoming government, however, finally let the peso float, immediately devaluing to the black market level. This alignment led to favorable pronouncements even if Argentina was still technically in default from its 2001 obligations.

In late January, it was announced that eurodollar banks were back in Argentine business:

HSBC Holdings Plc, JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Banco Santander SA are each providing $1 billion in loans, according to three people familiar with the matter who asked not to be identified because the information is private. Deutsche Bank AG, Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA, Citigroup Inc. and UBS Group AG will each provide $500 million, the people said. The interest rate is Libor plus 6.15 percentage points, the people said.

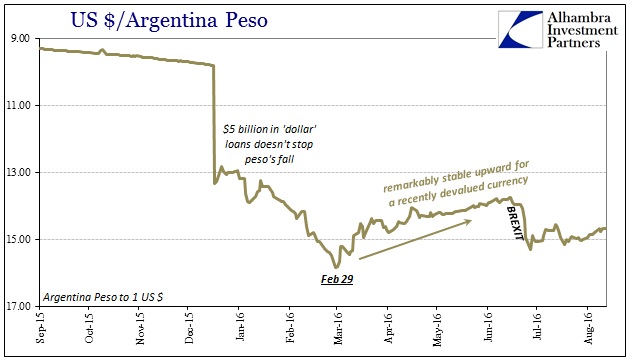

Those loans are reportedly backed by Argentine sovereign bonds, though I did find any word whether they was dollar-denominated collateral posted as well (I suspect there was some form of credible assurances). Despite such good fortune even in “dollars”, however, the peso kept devaluing. It had traded officially at about 9.80 on the day before the float, 13.334 the day after, but was 15.84 on February 29 before finally turning around. Yes, the same day the real fell below 4.00, the peso began also to strengthen.

It is entirely possible that positive sentiment globally post-February 11 and spillover from any additional optimism about Brazil could account for this correlated inflection point. The IMF call sheets for Argentina, like Brazil, provide some hint otherwise.

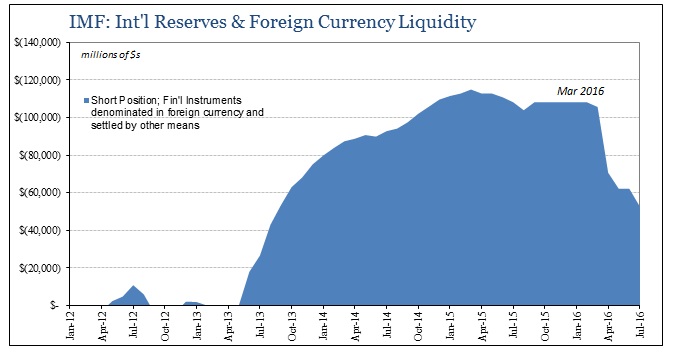

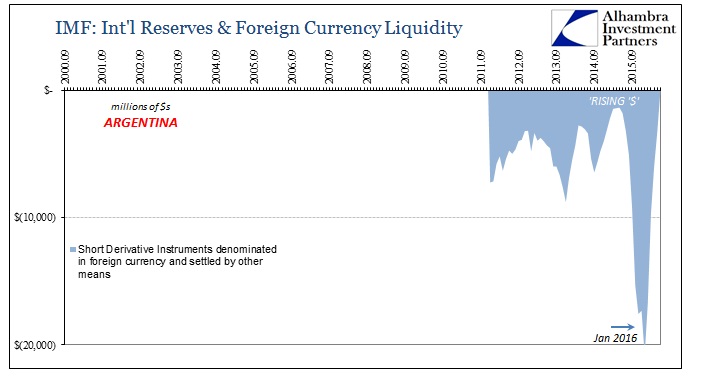

Argentina had in its worst moments late in 2015 began to engage in forward operations that like Brazil’s position were short “financial instruments denominated in foreign currency and settled by other means.” The amounts were enormous, particularly of a country of that size. Though Argentina was no stranger to forward or swapped “dollar” positions, it had started the year short just $3.1 billion against total reported reserves of $31.5 billion. By December 2015, the month of devaluation, that short position had exploded to $17.3 billion against total reserves of just $25.5 billion. The “dollar” loans in January had increased reported reserves to just over $30 billion for the month, but the short position only grew, now to more than $20 billion.

But then, in February, like the peso’s sudden strength and confidence, the short position just started to disappear. As of the latest IMF report for the month of June 2016, the short position is gone, zeroed out for the first time since it was originally reported in late 2011.

There are various possible explanations, especially considering the normalization of the market price of the peso to the black market price. Back in December, the new government announced an agreement with grain exporters to that was supposed to bring in $400 million a day in exchange for pesos (priced more consistently), while Argentina’s central bank converted a $3.1 billion CNY swap into “dollars.” In early February, Banco Santander Rio SA began offering a 4% dollar deposit rate in order to entice Argentinians to deposit what is believed to be a considerable dollar cash hoard into the bank. Maybe these processes combined would be enough.

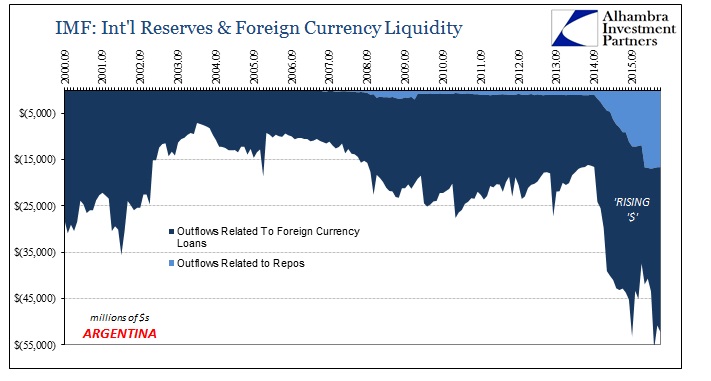

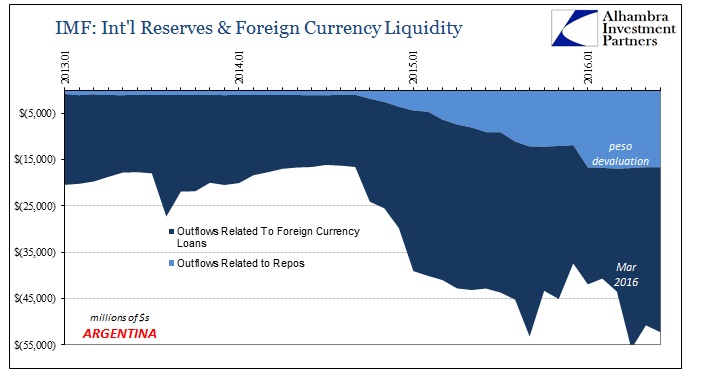

But Argentina still appears to be significantly on the hook for currency loans, at least foreign currency loans which we can reasonably assume are almost completely dollar-denominated, as well as repos. Despite stabilized overall reported currency reserves, there is still an enormous outflow liability in relation to “dollar” repos that had become necessary in later 2015, as well as a noticeably large increase in outflows related to foreign currency loans starting, like Brazil’s long derivative position, in March.

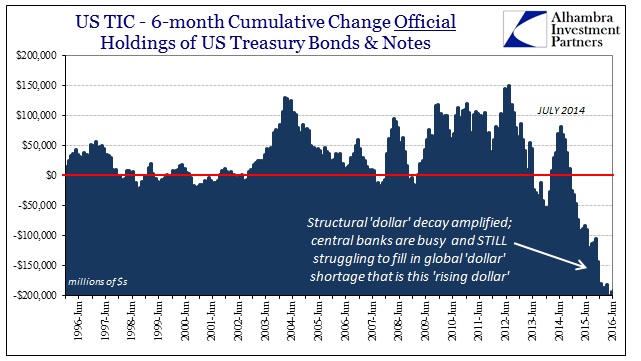

None of this is, of course, a smoking gun, nor is it meant to be. It is intended to add to the picture of what might be different in 2016 as compared to 2015. We already know that central banks are a bit more awake and aware this year after having survived, if that is the right word, January and February. What these South American stories might indicate is that some unknown entity or central banks or whomever has intervened in “dollar” markets in substantial fashion. If that is the case, it is likely that the intent is to stabilize these currencies, maybe even all EM currencies, such that the “rising dollar” isn’t completely arrested but might instead be of much less disruptive potential for these countries but really the whole global system.

I have my own suspicions about who that might be (or several “who’s”) and where these “dollars” might be coming from (cough, LIBOR, cough), but without evidence I am unwilling to publish blanket speculation. Again, the data I have provided here isn’t terribly overwhelming, but in my view it’s enough to warrant serious consideration and further scrutiny. If nothing else, it should at least totally affirm the EM if not global “dollar” problem and shortage as the primary deficiency during this “recovery.” As to exactly why and what that means going forward, that is still a much bigger story that isn’t yet fully written, where the final chapter(s) will not likely be of South American prose.

Stay In Touch