The simple fact of the matter is that 2012 wasn’t supposed to happen. By every orthodox prediction and theory about the set of tools deployed after the Great Recession (after it, the first clue) there was no reason to suspect anything but the usual cyclical occurrences. Sure, the recovery would be weak because the recession large, but retrenchment was never even considered. The recovery might be somewhat shallow, but there was no way it could be bent or durably altered.

The first rebuke to the mainstream came from Europe. Though the European economy would fall right back into recession so soon after the “Great” one, it was easily dismissed as a product of Greece, debt, and the demographics of Greek debt. So tantalizing was its allure, the European debt crisis of 2012 even made its appearance within excuses for China.

China’s fixed-asset investment has already started to pick up and a jump in spending on railway construction would echo the expenditure on rail lines and bridges that was part of stimulus during the global financial crisis. A decline in foreign direct investment reported by the government today underscored the toll that Europe’s debt woes and austerity measures are taking on Asia’s largest economy.

I honestly have no idea how Bloomberg News got from European “austerity measures” to the vast Chinese slowdown other than to skim the surface of stories that just happened to be occurring at the same time. In other words, it is the same logical fallacy that pervades mainstream “understanding” of how the world supposedly works; correlation doesn’t suggest causation.

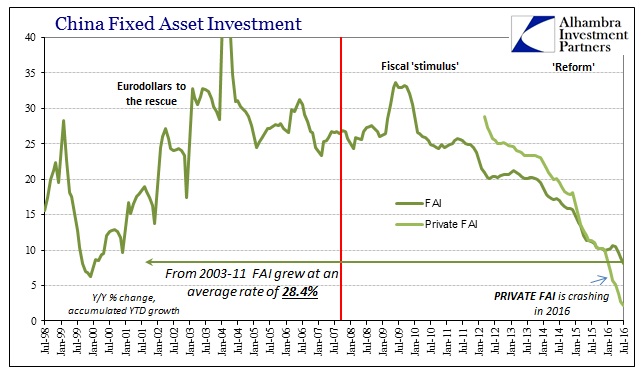

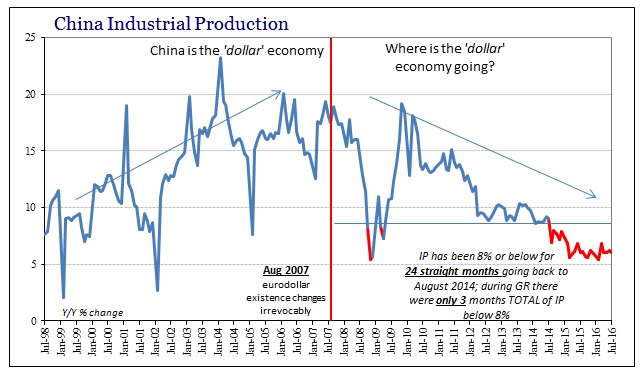

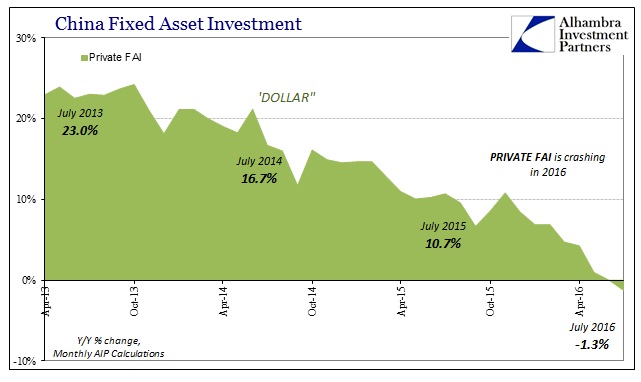

China experienced 2012’s sharp retrenchment with an unusual vigor. As the article quoted above alludes to, the Chinese responded with equal energy on both the monetary and fiscal sides. The fact that they even had to do it, like everywhere else in the world, including the US that would follow into QE3, should have raised serious questions about not just the possible efficacy of any policy “stimulus” but more so about exactly what the global context was saying. Instead:

“China’s stimulus may be stronger than the market has expected,” said Zhang Zhiwei, a Hong Kong-based economist for Nomura Holdings Inc. who formerly worked for the International Monetary Fund. “There will be more positive signs in the coming months to confirm that China’s pro-growth policies are taking effect.”

The Chinese government itself took to almost gloating in early 2013 about its having to redo “stimulus”:

When it comes to the Chinese economy, it seems that there are none so blind as they who will not see. For once again, hard facts last year got the better of those who are forever predicting doom.

In the fourth quarter, China’s economy picked up steam, with GDP growing 7.9 percent year-on year. This contrasted with the EU and Japan, both of which have registered new downturns, and the US, where economic growth last year is likely to have been below 3 percent, which is anemic compared with previous recoveries.

It was an odd pronouncement since the answer was written and acknowledged at that same time about what was essentially the real problem; meaning that this was not a contest among individual global participants, it was a shared struggle:

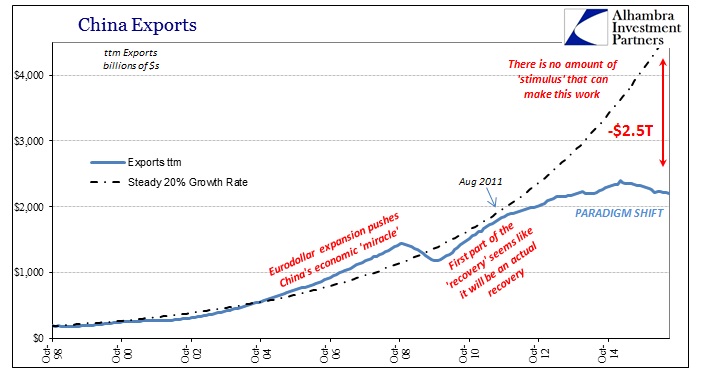

The initial problem in early 2012 was simple. China’s economic policy makers underestimated the problems in the developed economies. China’s official prediction of 10 percent export increase in 2012 could not be achieved without significant growth in developed markets. This did not materialize – the US economy grew slowly while Japan and the EU’s fell into a new decline. Consequently, as is now officially stated, 2012’s export target will not be achieved.

In fact, such growth never materialized and none of the export targets have been close ever since. “Stimulus” in China was supposed to offset weakness in the end markets for Chinese goods even though the same kind of “stimulus” in those end markets left China needing another round of its own “stimulus.” There is nothing about such a statement that smells of cyclicality.

It was only a surprise to those who continued to deny the possibility – that the Great Recession wasn’t a recession. As this IMF paper from November 2012 attempted to quantify, a serious slowdown in Chinese investment would be a global problem.

The spillover effects from an investment slowdown in China also register strongly across a range of macroeconomic, trade, and financial variables among G20 trading partners as well as world commodity prices. Within this group, a China FAI decline would have a substantial impact on capital goods manufacturing economies with relatively sizable exports to China (in percent of own GDP) and are highly integrated with the rest of the G20 such as Germany and Japan… Important commodities exporters, such as Canada and Brazil, would experience non-negligible spillover effects on export growth which would translate into somewhat significant output loss and slowdown in overall economic activity. [emphasis added]

The official policy error was, and continues to be, how this “slowdown” was framed. Like everything else, it was filtered through the lens of another cycle; recession or not recession. In other words, even this paper was written as a worst case if China fell into a sharp slowdown right at that moment. It was simply never considered that China, or any other major economy, and thus the world economy, would experience everything that was written and included in the IMF paper only drawn out over years rather than months or quarters. Thus, when it looked like China would skate by in early 2013, the paper, and the possibilities that were raised, were forgotten as unnecessary doom and gloom.

That meant also in early 2013 economists and policymakers were viewing the potential for global spillover as minimal because China’s slowdown was at that time undetected by cyclical calibration. Any market indication that suggested otherwise, including and especially commodity prices, was simply ignored under the binary framework of China avoiding a full pullback in late 2012 and early 2013.

It took several more years, but all those negative traits quoted in the IMF paper above have become not just the literal economic truth, but a seeming trap from which nobody appears capable of escaping. That alone demands more urgency not of more “stimulus” but in explaining why past programs had so little effect here or there or anywhere in between. And that gets us back to 2012 and actually trying to understand why a second round of “stimulus” was needed in so many places and all at the same time in the first place.

This misidentification of what really transpired in 2012 continues to be the primary intellectual hurdle. It was never specific to Europe, as all that was a symptom of wholesale finance and the global eurodollar system. It should have been clear, especially to the Chinese, that what was going on in Europe was a banking issue and that meant global money. After all, it was none other than PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan who wrote for the BIS in March 2009 (of all times) that:

The outbreak of the current crisis and its spillover in the world have confronted us with a long-existing but still unanswered question, i.e., what kind of international reserve currency do we need to secure global financial stability and facilitate world economic growth, which was one of the purposes for establishing the IMF?… The acceptance of credit-based national currencies as major international reserve currencies, as is the case in the current system, is a rare special case in history. [emphasis added]

The recurrence of a banking abnormality of such massive scale could only indicate more problems in the true global reserve currency, still reeling from the panic, primarily the “dollar” that was by far the most important of those “credit-based.” Perhaps the Chinese were being more optimistic that the ECB, Federal Reserve, and the globally-connected cadre of other central banks could cobble together a solution. Based on what, however, isn’t clear; again, the simple fact of 2012, really the second half of 2011, should have at least suggested a very realistic possibility that this “rare special case” of credit-based global money supply was terminally broken. And if it wasn’t evident enough in 2013, a potentially understandable position, it sure was by 2015 and that much more so in 2016. The primary cause of global trouble in 2012 was never really European debt, it was eurodollar.

When we say the money supply is shattered, however, that usually conjures images of 1929 and the early 1930’s; or even just 2008. Again, I have little doubt that so much confusion in the 2010’s is due to nothing more than the slope of the decay. We are all practically trained for that crash scenario – and nothing else. If some monetary aspect is broken, it can only mean, so it is believed, a direct, substantial, and immediate crash – economy and/or markets. As I wrote last week in the “impossible” reemergence of this mysterious “fear economy”:

The second fallacy is how all that might manifest as different from the Great Depression or other past eras of unusual money tightness. There is every reason to suspect that monetary innovation and changes have increased the flexibility by which the money and banking could absorb “tightness” such that it need not turn into the worst of the worst cases; 25% declines in prices and 37% declines (as Milton Friedman calculated of the collapse portion of the Great Depression) in overall money supply. But this would create a new set of challenges whereby symptoms are far more ambiguous; an obvious monetary collapse leaves little argument for cause and effect. Gentle money tightening would confuse economists with the “strange” or “unexpected” inability of intentional policy, no matter how intense and large, to hit the inflation target or to escape the low growth “trap.”

And so we have all the elements suggesting that which was even predicted by so many of the “right” channels, particularly in and around China, to put together the monetary answer, save one: the slope. It has been a slow-motion crash to which economists then see no crash at all. Maybe there is a semantical argument to be had, but at this point it truly doesn’t matter. It happened; it is still happening.

It follows the textbook case of “deflationary” pressure with only that one time-specific factor being different. Apparently, that is enough to throw off all the “experts.”

Stay In Touch