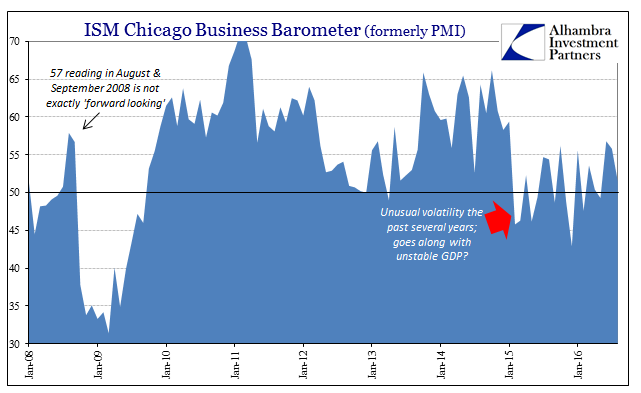

For October 2014, the ISM estimated that its Chicago Business Barometer was a blistering 66.2. Encompassing much of the Midwest and a good deal of auto and parts production, that level seemed to make sense. As any economist would say then, the US economy was on the verge of a breakout and according to the labor statistics maybe even one of unusually good strength and duration. Two months later, however, the Chicago BB was down almost eight points to 58.3; just two months after that, for February 2015, the PMI was shockingly below 50 and quite far below at 45.8.

Since then, the index has been all over the place. It almost counts more as entertainment than actual meaningful interpretation from month to month, but there is, I think, something useful to the overall sawtooth of the past two years. It is emblematic of the unevenness of this economy as it swings from very real recession fears to almost pure elation of seeming to skate by; only to see such jubilation ruined in short order all over again. There is information in the schizophrenia.

After falling below 50 again in summer 2015, the PMI was above 54 in July and August, only to drop to 48.7 in September in the aftermath of “global turmoil” – and then rebound to 56.2 by October as the FOMC assured the world there was nothing lasting about it. Of course, the Chicago BB instead fell to a “cycle” low of 42.9 in December before jumping almost 13 points in January alone, to 55.6 – and then dropping back below 50 again in February.

It seems rather clear from that volatility that nobody can make sense of this economy during the “rising dollar.” It certainly is nothing like what was expected in the orthodox mainstream version of “overheating”, but it also time and again stops short of full recession. There is never any breakout in either direction. As I wrote earlier today with regard to the eerie similarity of Canadian GDP:

There is no getting away from the “rising dollar” and its effects on the global economy. It’s not recession, at least not yet, but as always that is actually worse. Any economy that shrinks and then doesn’t actually recover from it is a disaster in good part because nobody seems able to recognize what is truly happening. It results in this increasing wedge of mistrust where economists say the economy is growing yet the people know it really isn’t. Positive numbers are not the goal nor even close to any reasonable, rational standard for success.

Recognizing instability for what it is is the only way out of this global mess.

The Chicago PMI was 50.4 in April and 49.3 in May 2016 before spiking to 56.8 in June, and now back to 51.5 all over again. If the last two years aren’t an indication of such instability then nothing is. The trend doesn’t follow the textbook definitions for how an economy is supposed to progress – in linear fashion toward either recession or its more welcomed opposite. Nothing about this economy here or everywhere else is textbook, except of course if you factor global money as an exercise in bank balance sheet constraints.

On the one side there is Janet Yellen and her $4.5 trillion balance sheet talking about “full employment” and stoking nothing but positive expectations; but on the other there is this nagging reality that just won’t go away, as if the economy were the victim of some uniquely slow (monetary) strangulation:

The rare disappointment in the two chains’ financial results took a toll on their stocks. Shares of Dollar General fell 16% to $77.40, while Dollar Tree shares declined 9.4% to $86.

Dollar stores have been a relative bright spot in a troubled retail sector as recession-weary shoppers flocked to their low prices and convenient locations near residential areas. The two chains have been growing rapidly as others retrench.

As Dollar General’s CEO Todd Vasos said on his company’s quarterly earnings conference call, “I know that when we look at globally the overall U.S. population, it seems like things are getting better; things have not gotten any better for her [the core shopper]. And arguably they are worse.” For industrial Chicago as one global proxy, it seems as if businesses swing between those two extremes, going nowhere in the process. In that volatility is the ethos of this “rising dollar” phase of the slowdown/depression.

Stay In Touch