For some reason Alan Greenspan’s opinions are still taken seriously. No one single person has done more to damage the economic long run that his Keynesian training told him would never matter. We are living in that increasingly desolate long run, and yet somehow to the media to some nontrivial extent beyond it he has maintained credibility. What is most offensive is that he now acknowledges the economic despondency but only as if it was just mere circumstance or accident.

In a Bloomberg article today, the former Fed Chairman is quoted to be worried about the “crazies.”

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan voiced concern that the U.S. economic and political system could be undermined by what he called “crazies.”

“It is the worst economic and political environment that I’ve ever been remotely related to,” Greenspan, 90, told a conference in Washington Tuesday evening sponsored by Stanford University and the University of Chicago.

This is no mere accident, however, as there is a direct line from his “stewardship” to the increasingly worrisome possibilities that become more probable the longer this depression continues on. Historically speaking, lengthy periods of stagnation do not spontaneously turn into rapid and healing growth all of a sudden, nor do elite policymakers suddenly figure it all out. In almost every prior instance, catastrophe of some degree forces a reckoning and only then are solutions presented and executed; human nature is apathy until that point but immediately turns action once it is reached.

In terms of monetary policy, Greenspan long ago recognized that there wasn’t any anywhere in the world. As early as 1996 in his infamous “irrational exuberance” speech, there was the “maestro” admitting that the very concept of money had long ago gotten away from central banking.

Unfortunately, money supply trends veered off path several years ago as a useful summary of the overall economy. Thus, to keep the Congress informed on what we are doing, we have been required to explain the full complexity of the substance of our deliberations, and how we see economic relationships and evolving trends.

There are some indications that the money demand relationships to interest rates and income may be coming back on track. It is too soon to tell, and in any event we cannot in the future expect to rely a great deal on money supply in making monetary policy. Still, if money growth is better behaved, it would be helpful in the conduct of policy and in our communications with the Congress and the public.

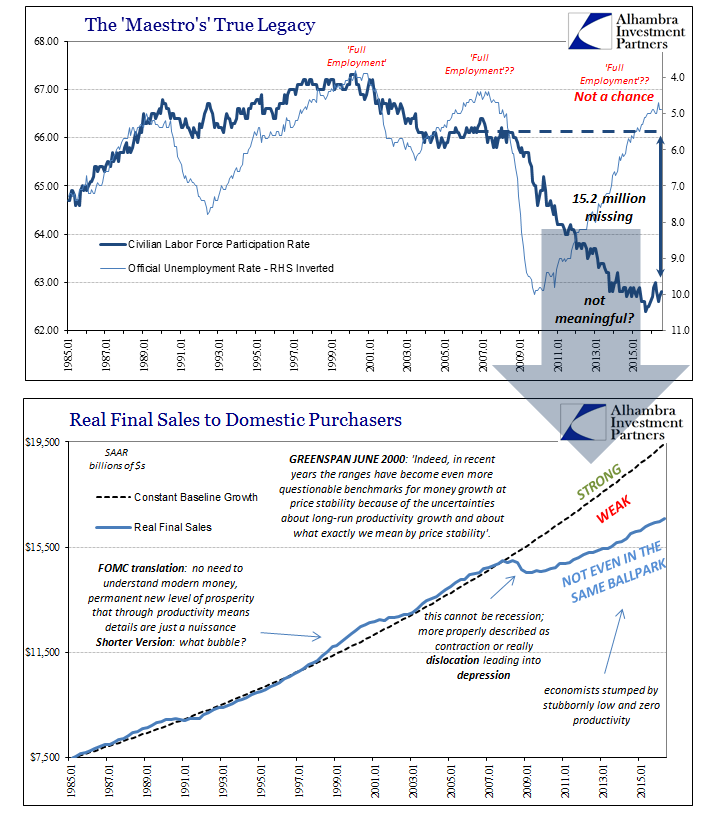

Did money ever become “better behaved?” Of course not, as it was just as unreasonable to suggest then as it would be to do so now twenty years later. We need look no further than Greenspan’s own words in June 2000 to settle that issue:

The problem is that we cannot extract from our statistical database what is true money conceptually, either in the transactions mode or the store-of-value mode. One of the reasons, obviously, is that the proliferation of products has been so extraordinary that the true underlying mix of money in our money and near money data is continuously changing. As a consequence, while of necessity it must be the case at the end of the day that inflation has to be a monetary phenomenon, a decision to base policy on measures of money presupposes that we can locate money. And that has become an increasingly dubious proposition.

How that doesn’t disqualify him and all his compatriots from further discussion about money and especially economy can only be a matter of ideology shared not just among economists but with the media itself. His Fed abandoned its primary mission because math; regressions alone told him and the rest of them that interest rate targeting would be sufficient monetary control even though there was every indication that just wasn’t the case. As his ability to define and measure money had only become worse by the middle of 2000, perhaps the gigantic stock bubble that had just burst was enough of a common sense clue that what was wrong in money shouldn’t have been so easily dismissed.

Even in what he said at that FOMC meeting, which is a matter of public record, you would think that any central bank caught in a position of not being able to define money would immediately change that.

Did the Fed expend every resource to rectify this knowledge gap? No; emphatically no. Quite the opposite as they openly proved in discontinuing M3 in March 2006, writing in the official press release that the “costs of collecting the underlying data and publishing M3 outweigh the benefits.” Any institution that made such judgment only a little over a year before the repo and eurodollar markets blew up should be prohibited from all discussions going forward.

And that is really the point, for me as well as, ironically, Mr. Greenspan. He knows. When the wheels finally come off of what is left of the eurodollar system, propelling the global economy into whatever kind of phase shift that will bring about, there will be a full accounting. Unlike now or what should have come from 2008, there will be more intense interest in past public records where the causes of this decade-long (so far) disaster will be traced. No one will be so fooled as to not be able to connect his “dubious proposition” about money to then his “conundrum” and finally the absurd “global savings glut” that all presaged first the Great Recession and then the by-then more established and accepted fact that it was never a recession. If this is indeed the “worst economic” environment as he claims now, and the evidence is overwhelming that it is, it was born in his intellectually incurious ideas.

Alan Greenspan is shamelessly trying to get ahead of what he seems to be calling the mob, the crazies who at some point will start digging into what he actually did at the Fed rather than simply accepting the myths that he still manages to live by. When that happens, we will see exactly who is tarred with the disapproving pejorative of “crazy.” I have little doubt that it will be he who is stuck with that word and many more far less flattering, a provably fitting end to and for the “maestro.” It won’t be crazy at all; it will be in his own words.

Stay In Touch