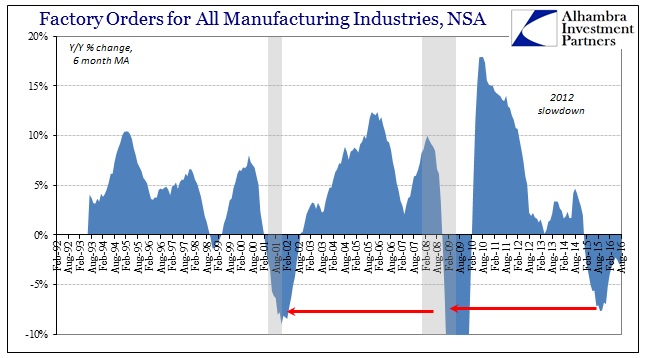

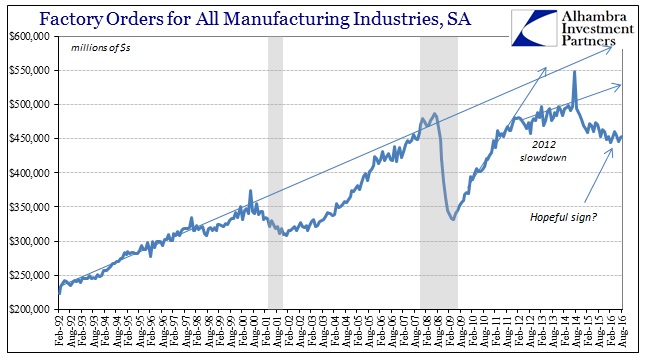

Factory orders rose 1.1% year-over-year in August, the first increase since February. Like February, however, it isn’t clear if the gain is due to actual organic growth or seasonal factors. The seasonally-adjusted series for factory orders fell 1.6%, the difference likely attributed to July. Orders rose by a considerable amount in that month on a seasonally-adjusted basis even though unadjusted they fell at the quickest pace since last fall. Combining July and August unadjusted, factor orders declined by 2.6%, which is almost right at the 6-month average.

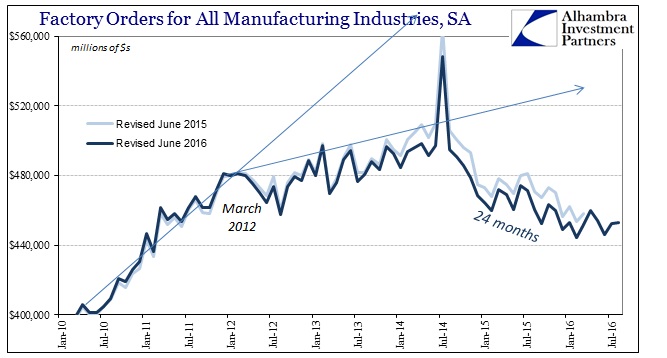

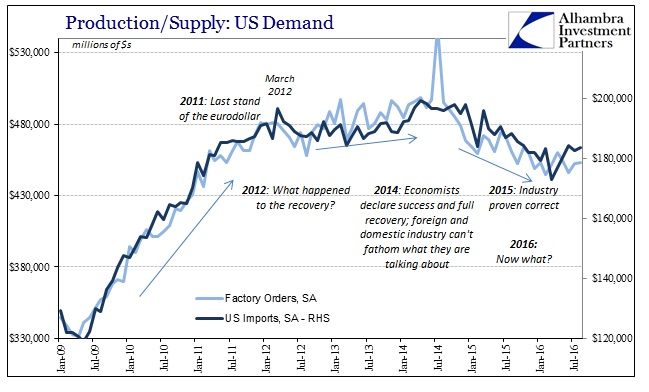

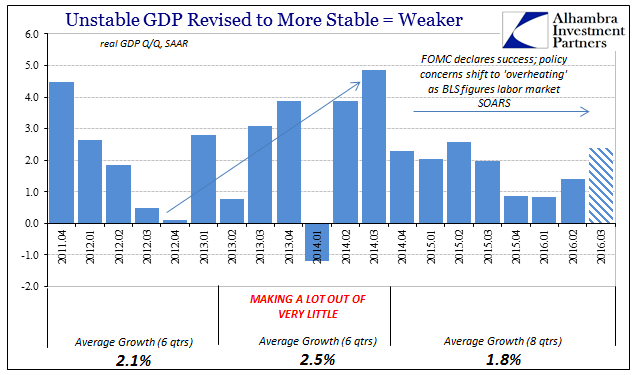

At $453 billion, factory orders are still 9% less than the peak in June 2014 (and 17% less than the abnormal surge in July 2014 that really can’t be counted as the peak for comparison purposes). As with updated US trade statistics, especially imports from China, US “demand” for goods remains suspiciously subdued while inventory levels continue to be at extremes. These differences are significant and account for what we have seen in GDP, for instance. Final demand from consumers has been unusually weak for some time, but in GDP especially in 2014 inventory added what looked like acceleration. With inventory now flat to only slightly positive, the underlying weakness is exposed even by GDP.

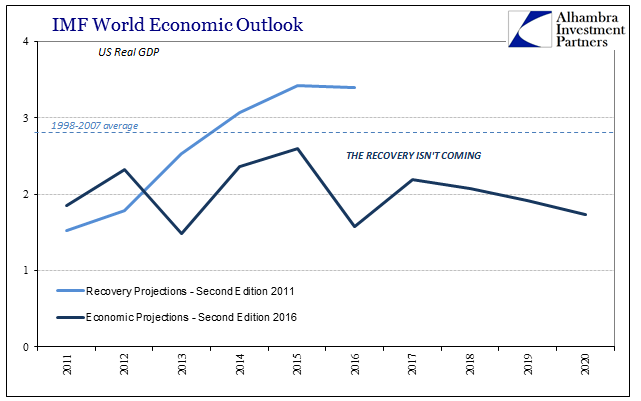

Production both here and overseas can only continue to be suppressed by the lack of demand. That may be why, belatedly, the IMF radically reduced its estimates for not just real GDP growth in the US but across all advanced economies as its models finally calculate weakness as a tangible core property and not just an irrelevant, “unexpected” temporary hurdle.

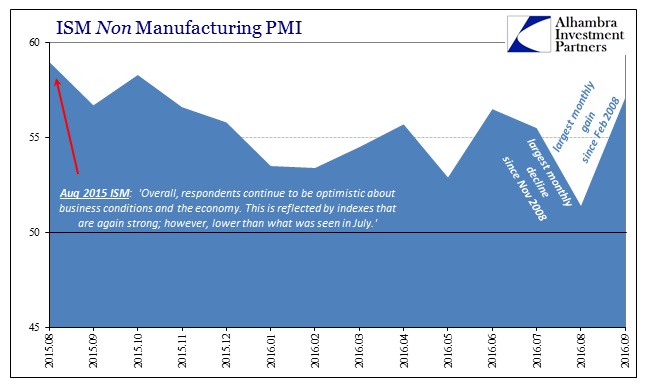

It is the only real constant these past few years, as various economic accounts are at times all over the place. This almost economic schizophrenia has been extreme this year, perhaps including factory orders and US exports in August. The ISM Non-manufacturing PMI, for example, also exhibited the same troubling volatility, especially in the past two months. Falling to just 51.5 in August in what was the biggest single monthly decline since November 2008, the PMI surged in September in the single biggest monthly increase since February 2008.

By turn, the mainstream goes from a high degree of seemingly warranted concern to unbridled jubilation apparently just as justified in the space of only one month. This kind of volatile behavior in both accounts and commentary has, again, become quite common; unusually and importantly so. It reflects the inability of underlying economic agents to make sense of this economy, which is recessionary one month and then Janet Yellen-esque the next.

It obscures the central proposition that is reflected in the overall arc of data like factory orders. Though there may be violent swings of emotional analysis, in general the economy has fallen further behind (after starting this “rising dollar” period already in a serious growth deficit) when all the ups and downs are counted or blended. This realization isn’t much appreciated because for every down month that conjures real fears of recession, any following up months seem to, for conventional analysis, completely dispel them. Thus, the next time a down month appears, which doesn’t take long, it is treated as if unrelated to all the prior ones even though they far outnumber the positives. It’s like in months like now, the “recession clock” is reset to zero when utilizing the cyclical perspective is in the first place misleading.

The real concern doesn’t, however, relate to recession, it is the fact that after two years there is still an overall negative trend even if unusually shallow by its amplitude. Recession isn’t the worst case; the worst case is being stuck in this back and forth any longer where the lack of recession actually helps keep the economy locked into its depression because officials and policymakers can continue to claim that this is growth – when it so clearly, on the whole, is not. That was the realization the IMF models finally came to terms with, and it not only explains the current predicament but it also begins to suggest how to get out of it.

Stay In Touch