Maybe it is just too complicated to do much more, but for the most part central banks work in the here and now. They may stray from time to time into strategic thinking, but given the mathematical limitations of traditional statistics, weaknesses we all know too well in 2016, that is of limited value. Even in normal times monetary policy was conducted in very short timeframes; the FOMC’s Open Market Desk conducts actual operative policy within maintenance periods of just two weeks.

Even the ancient doctrine of currency elasticity is intended for immediate circumstances, not as some general rule of consistent practice. In very broad terms, when confronted with a liquidity problem the central bank is a creature of right now; tackle the problem in front of you because it is a temporary problem. There is, however, no chapter in the neo-Keynesian central bank handbook on how to handle a chronic funding shortfall.

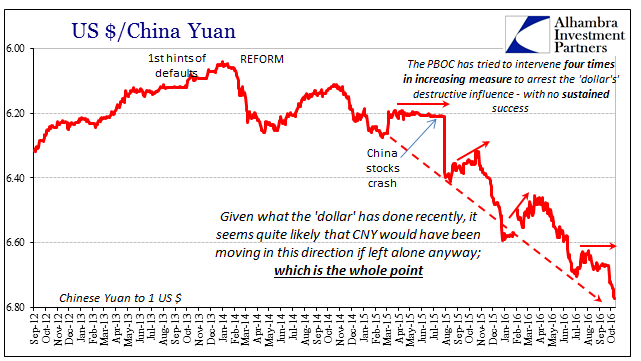

There was a section dedicated to foreign central banks in treating with a dollar problem, but I would hope that by now the text has been discarded as less than useless. Economists had determined from the Asian flu experience, as little as they felt necessary being entirely uninterested in money, that to overcome a structural dollar problem central bankers need only access huge stockpiles of dollar assets while being aided by the relief valve of a floating currency. Country after country since 2013 has proved that folly.

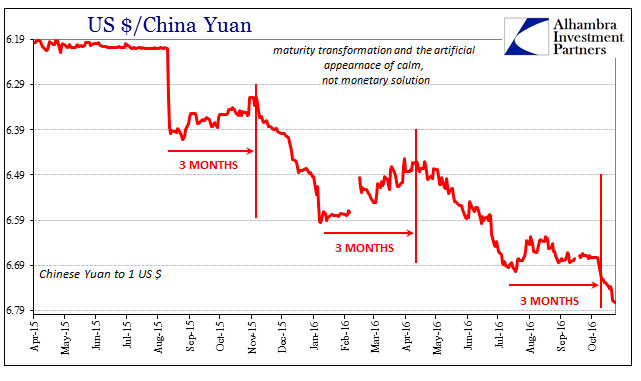

From the start, the problem was never dollar but “dollar”, a distinction of many dimensions beyond the purely legal. Unlike the dollar, the “dollar” comes in various formats including an often variable time component. Though “dollars” can be of any maturity, they so often remain close both as a matter of cost and as one of that central bank mantra – focus on the here and now. Thus, any forward operation, whether direct or as cover for local banks, ticks in often very clear three month intervals.

As I wrote in early January looking back at last August for clues as to what was about to come:

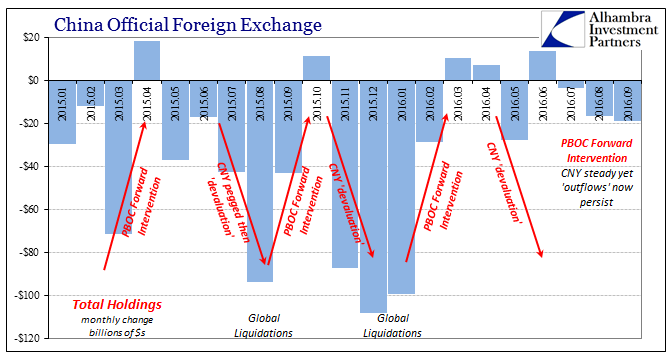

China did what it was supposed to do in accumulating, purportedly, the largest stockpile of forex “reserves” in human history. In fact, the Chinese made that forex the very basis (subscription required) for their internal financial mechanisms with regard to money and market liquidity. And yet, for “some” reason, China was subjected to great strain and even open disorder anyway; forex reserves don’t seem to have quite the effect or give quite the ability economists have expected for nearly the past two decades. Instead, to try and quell outright hysteria in August, and surely starting before it, the PBOC certainly resorted to swaps, forwards and likely an entire array of wholesale re-orientations. For a time, they, like Thailand in early 1997, appeared to work; it was certainly enough to fool economists.

Instead, we find the PBOC struggling to maintain a steady currency only to find that exactly three months after each of those efforts they have made their own task that much more difficult. It was nearly as regular as a ticking clock; so obvious that even the IMF eventually figured (some of) it out.

That is the ironclad reality of “traded liabilities”; they all come with expirations and maturities. Once the interventions are initiated, the clock starts ticking on the “next one.” Having gone through two full cycles now, the wider world seems to be catching on especially as “devaluation” fades toward obscurity. It isn’t really hard to figure out the connection even if its exact nature is foreign in so many ways; when China “devalues” the rest of the world goes in the toilet with it. Thus, it is highly relevant to figure out what the PBOC was doing, exactly, in January and February this year so that we might anticipate April and May.

I wrote that in March, and sure enough after three months the next wave of devaluations hit staring in April, intensifying in May. By July, CNY was down below 6.70 if but briefly, suggesting yet another reset to the “ticking clock” timed to strike in mid-October; more and more appears to have done so.

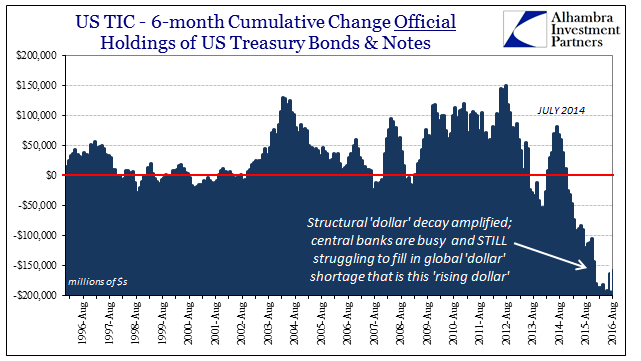

It wasn’t just the IMF who noticed the regularity; other foreign central banks have as well. If there is a difference between this year and last it is this half-awakening. It appears very much as if central banks around the world in 2015 were content with what their Asian flu-inspired textbook said about defending against the dollar; in 2016 it is quite clear they are now trying as best as they can to instead more suitably deflect the “dollar.”

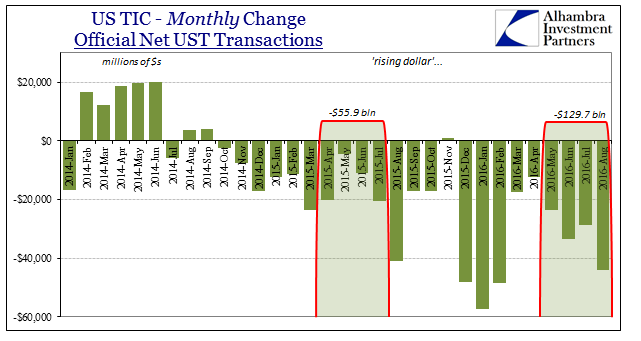

In the four months leading up to the CNY “devaluation” in August 2015, and the liquidations that from the traditional dollar view still don’t make sense, the TIC data shows total foreign official sector “selling UST’s” of about $56 billion; in the last four months of data through August 2016, the total net has been -$130 billion. That will certainly make a difference in how “dollar” problems play out downstream – but do nothing about the “dollar” problems themselves.

Instead, as with any such wholesale interventions, they are setting themselves up for worse down the road. The PBOC and China are at the forefront of that experience, as internal RMB conditions show that quite and dangerously well at the moment.

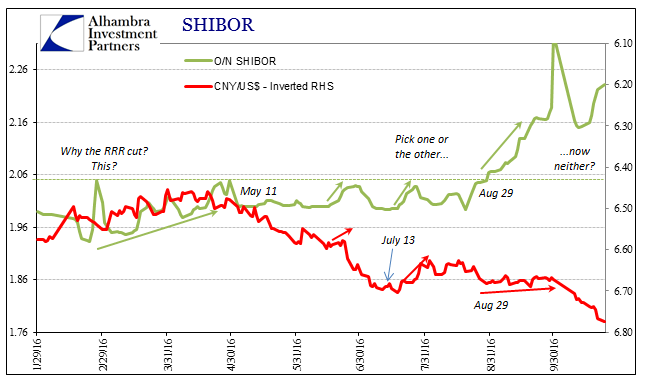

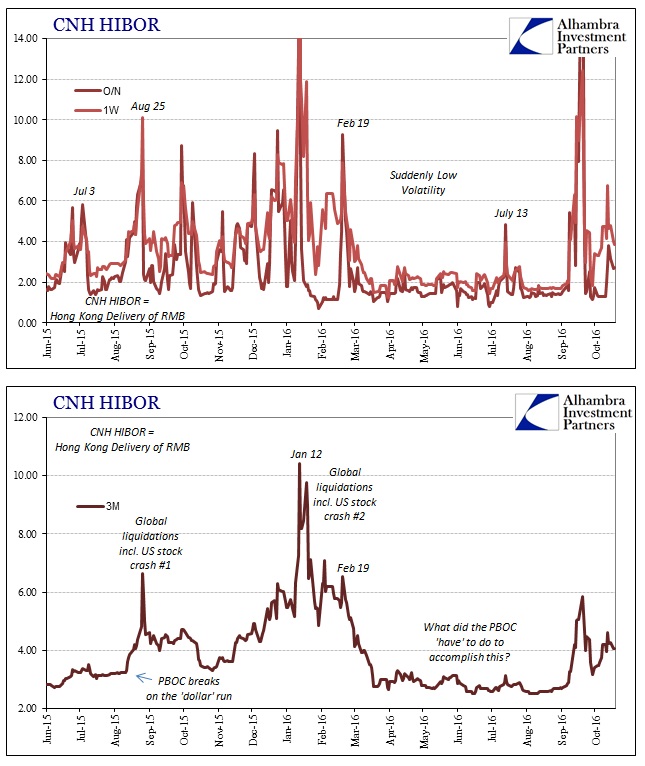

Whereas in months prior the PBOC was able to tradeoff between CNY “devaluation” for steady SHIBOR (internal onshore RMB liquidity), in this latest “tick” of the “dollar” clock it appears as if they can steady neither. Both CNY and SHIBOR are moving in the “wrong” directions, joined very conspicuously by offshore CNH in September.

These trends indicate only greater struggle for and of the PBOC, perfectly consistent with the central bank having been digging a bigger hole for itself for over a year. From the Chinese perspective, that much is very clear throughout the RMB statistics. To start with, “capital outflows”, as they are taken by mainstream convention, have increased (bigger negative) in official holdings the past few months (through September) despite the artificially steady CNY exchange rate.

In the past, these intervention periods have been accompanied by what appear to be “inflows” that are really partial statistics that do not count these official maturity transformations. In March and April 2016, for instance, during that upward trend in CNY bought by PBOC “dollars”, SAFE reported +$17.35 billion that fooled many economists once again into thinking China’s dollar problems had been solved. In August and September 2016, by contrast, despite similar conditions for CNY, SAFE estimates now -$35.19 billion for the two-month period that shows the PBOC stressed more now by the protracted “dollar” issue.

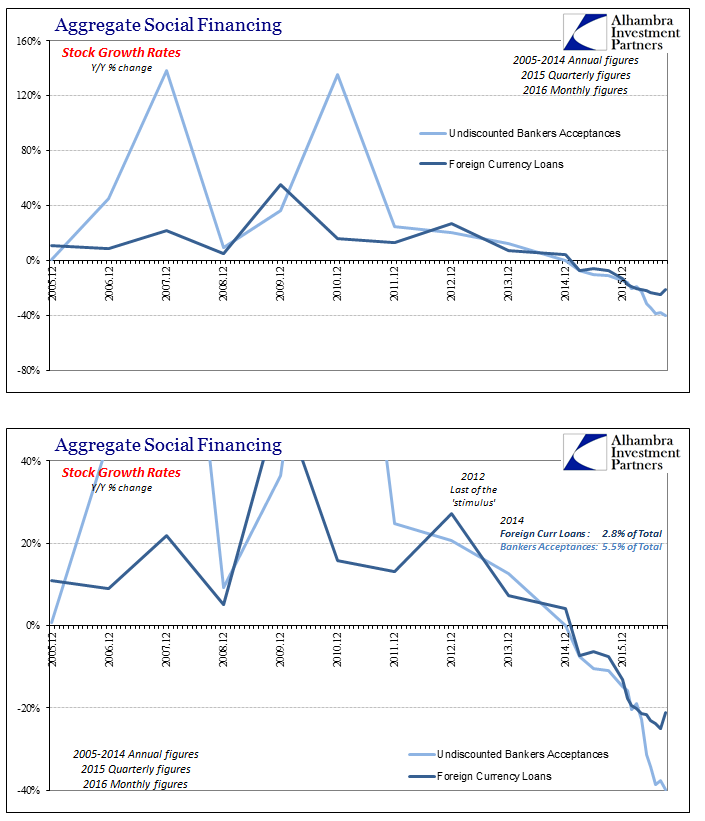

That is consistent with other RMB/China data that shows accelerating foreign funding difficulties. Foreign currency loans, a part of the China’s Aggregate Social Financing, turned negative in 2015, ending Q4 down 13% year-over-year. This year, foreign currency loans have contracted even faster, at a rate of more than -20% for each of the past seven months (thru September).

Worse, the bankers’ acceptance market has imploded, an even larger segment of China’s overall ASF. The rate of contraction is nearly 40% each of the last three months. While that indicates especially “dollar” issues it may also suggest how the Chinese are dealing with it from a position of bare trade survivability (avoiding “dollar” defaults). Though there isn’t near enough granularity to these numbers to show it, I suspect that Chinese firms/banks substituting oil for “dollar” payments from largely African former borrowers may be one factor (perhaps one of the biggest factors) as to why there are so fewer acceptances funding Chinese economic activity.

What this shows is that as suspected the Chinese if not global “dollar” problem is worse this year than last, in some part due to the combined if still largely Chinese efforts to deal with last year. What has changed is the intensity and intentions of global central banks and finance ministries, and not just in China. It is, it seems, a delicate balancing act where all that matters from the official perspective is surviving each of these short run episodes. Buying time in such a manner works when the problem is the usual if severe transitory disruption; those are usually solved by time that allows for calm emotion from within the private funding market. Now, however, the problem is time, leaving the “dollar” system to cycle through what has become the regularity of intensifying disruption where central banks’ biggest hope is that they engender nothing more than (righteous) angst and trading wariness. It is a greatly reduced standard for “success.”

That, I believe, is what these (sideways) markets are showing very well in parallel to the “dollar” as well as global “dollar” economy. In other words, there is asymmetry that has to be factored economy as well as markets; great downside risk without much upside to hope for. Whether it breaks out in an index or not, this “dollar” is absolutely still “rising.”

Stay In Touch