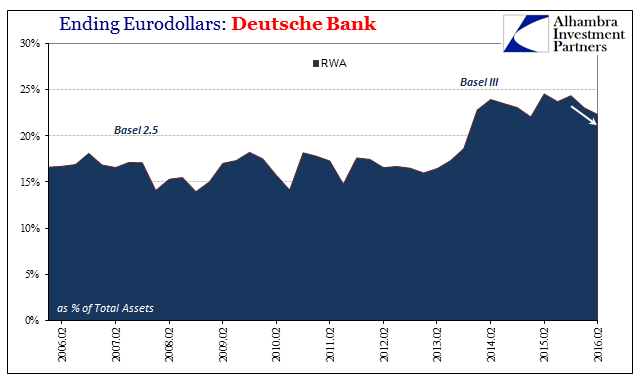

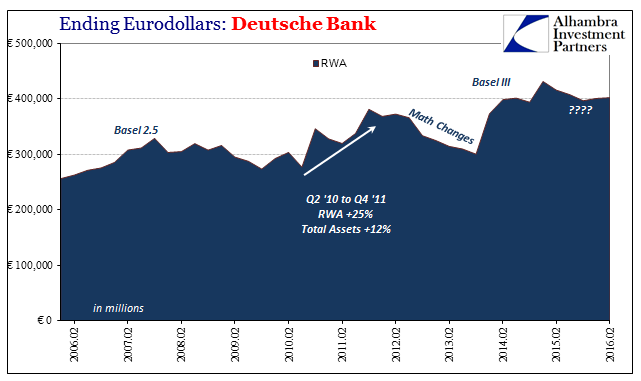

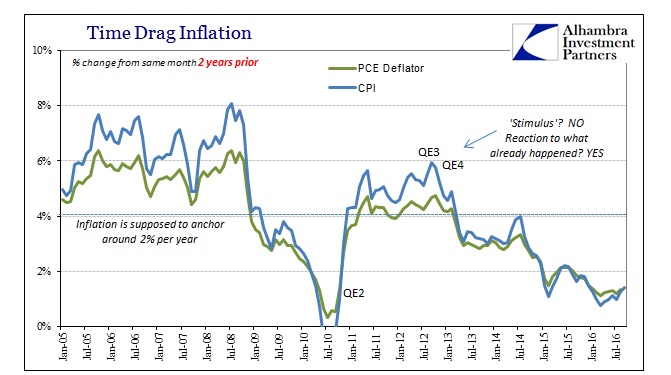

It has been my contention for some long while that one of the biggest parts of this “rising dollar”, that is, again, nothing more than a euphemism for the various ways in which there is a “dollar” shortage, is balance sheet math. The problem in as simple terms as perhaps possible is that positions were taken, balance sheets constructed, and “capital” allocated (through RWA budgets) all based on the idea that QE was money printing and that money printing would lead to inflation then recovery.

To find out instead that at the very least it wasn’t so simple threatens not just trading positions but balance sheet capacity itself. The eurodollar being not an actual thing, it is described as close as possible as balance sheet capacity. The world where QE is a failure is much, much different than the one where liquidity is overwhelming and perfectly fluid. To go from perceptions of the latter to the shocking reality of the former is an enormous undertaking that can only lead to shrinking and/or capital strain. In the shaky financial environment of the “rising dollar”, new bank capital is the less likely alternative.

The poster child of this shifting reality is Deutsche Bank; it has still the largest derivative book as well as past and current (I contend) proclivity to be more assertive in its math, perhaps by nature, perhaps by intent. At this point it might be worthwhile to review what I wrote about DB and math a few weeks ago as it related to this very problem. There are clues all over the place, starting with the unbelievably dubious “accommodation” the bank received from the ECB in the conduct of its last “stress test.”

When the Bank of Montreal, for example, forced itself to abide by new modeled outcomes, the result was this predictable expansion for RWA, meaning pressure on capital to do “something” about RWA that doesn’t involve raising more. That usually leaves limited options:

As I have been writing over the past year and a half or so, those concerns have already been raised – nobody noticed because they were too invested in trying to ignore how QE wasn’t what they all thought it was. When math starts to go bad, banks often face only stark and confusing (to the outside) decisions: let RWA’s rise and be forced to raise more capital at a time when questions about banks “having” to raise capital may make it more difficult and perhaps dangerous (Deutsche), or try to “earn” your way out by drastically shrinking operations and cutting back marginal resources before the auditors and regulators start questioning why your math doesn’t conform.

It is that last part that is where I believe Deutsche Bank may be stuck. In the past, a dramatic expansion in the derivative book would lead, as you would expect, to an increase in RWA (quite reasonable given that this jump in written positions occurs during the worst of times). In the past few years, however, DB’s published statements suggest that this is no longer a valid expectation; the bank is and has been during some of the strangest and most problematic hedging environments almost perfectly hedged.

The effect on capital ratios is thus similarly muted, as described above. Via effective hedging, purportedly, the bank has managed what looks like an almost perfectly even keel of capital and leverage during the most tumultuous conditions since 2011. And good thing, too, because the operational loss last year and the subsequent hit to “capital” via lower retained earnings dropped the Common Equity Tier 1 ratio down to 10.7%. If RWA math had led to a similar outcome as 2011, DB’s capital ratio would have been well under 10% by the end of Q2. All it would have taken was a €30 billion increase in RWA to push the capital ratio that far down, a place that this weekend’s news about the problematic “stress test” shows authorities aren’t willing to visit.

In short, if they weren’t so flawless in managing this math risk then RWA would rise significantly and capital ratios would decline at the worst possible moment. Even among the more innocuous interpretations still leave a globally important bank handcuffed by the need to improbably thread such an unthinkably narrow needle.

And so it is that Bloomberg reports today that Deutsche Bank has found inconsistencies with some of its swap positions.

Deutsche Bank AG is reviewing whether it misstated the value of derivatives in its interest-rate trading business, and is sharing its findings with U.S. authorities, according to people with knowledge of the situation.

The bank is looking at valuations on a type of derivative known as zero-coupon inflation swaps, said the people, who asked not to be identified because the matter is confidential. After finding valuations that diverged from internal models, it began questioning traders, the people said.

There is very little information, so I want to be perfectly clear that any interpretation is very speculative as to this specific incident. The article insinuates that this might be a case of traders doing something improper for their own rather than the bank’s purposes; and that DB is doing the right thing by first catching the inconsistency and then reporting it to authorities. That might actually be what has happened, and it could just as possibly be that there isn’t anything amiss here at all.

However, there are other possibilities that would confirm the “revolt of the math” scenario, especially given that the instruments in question are zero-coupon inflation swaps. As the name states, the fact that these are “zero-coupon” means cash flows are exchanged only at maturity, and therefore the price is all that changes during the course of the instrument’s life based on probabilistic models of outcomes. If you in 2013 were betting on 2.5% inflation ten years out because you thought QE would be successful, the value of your side of the contract would have fallen markedly starting in the middle of 2014 – unless your posted valuations aren’t set as much by current observations.

The consequences of that scenario aren’t just how they would affect, potentially, market values but also the flow of collateral. Though there are no cash flow exchanges here, some contracts require collateral posting upon certain marks. For the most part, these are interbroker instruments that don’t trade all that frequently, yet are still considered highly liquid. FRBNY’s Liberty Street Economics reported that overall traded interdealer volume in 2012 was $190 million a day, up from $100 million two years before, and a total (including client orders) of as much as $350 million per day.

Despite what is relatively thin volume and the low frequency of transactions it depicts, prices are easily derived from the obvious liquidity of inflation trading via other instruments, including TIPS and UST’s themselves. In other words, there is a great deal of market definition about inflation expectations, but then a somewhat open window of mathematical interpretation about how to turn those market prices of TIPS or the UST curve into an inflation swap price especially several years into its contracted life (almost half the volume is concentrated at the 10-year maturity).

As improbable as that might sound, it is actually official US policy as it relates to DB overall. The bank was given its second consecutive failed “stress test” in the US earlier this year not because of the Fed’s suggestion of capital problems but due to a perceived lack of systemic control, including “risk management.” When it failed for the first time in early 2015, the Wall Street Journal reported that the Fed wanted Deutsche to “fix flaws that could potentially destabilize a firm to the point that it needs support from the U.S. central bank.” What that really means is what I wrote at the time:

Banks are under enormous pressure to take enormous risk at the same time they are getting more heavily regulated against it, so they end up doing so in the most hidden, esoteric and complex manner possible. In the end, as you might be able to discern just from the language here, all this newfound complexity in regulation serves not to make banks less “risky” but rather only to give them [more] cover to obscure it all under a mountain of legalisms and bank operation jargon that is impenetrable to most regulators themselves let alone the public that has the largest stake in all this (TBTF).

Today’s Bloomberg report could very well be just some rogue traders padding their own bonus structure, or it could be more evidence that there is indeed a big problem in the math, one that has been an issue at DB for more than just 2016. The conditions of 2016, as 2015, however, are what set it all up because, as even economists are admitting, the recovery isn’t coming and the impossible “dollar shortage” is so palpable they are forced to see it even at Harvard.

The problem was never regulations themselves, though they aren’t helping, rather it was QE. What happens when you bet on it thinking it easy money to absorb a lot of risk being laid off elsewhere, and then the world shows instead just how wrong a bet that was? I believe we are in the early stages of finding out.

Stay In Touch