Where do we go from here? If the monetary system is broken, how do we fix it so that the global economy can be mercifully released from the “dollar’s” gripping vise? The short answer is that it is too complicated to contemplate in this setting. A better answer is that I don’t know because there is a great deal that I know I don’t know. In truth, there is likely a lot that nobody knows, an element equal of frustration and terror. And it is that part that stimulates questions about how to find an escape. After all, almost a decade is enough since the world will not be able to follow Japan.

The generic answer is often stability, as I am just as guilty in taking the easy way out by leaving in that shorthand. But “stability” means different things to different people; there are those who propose that the Federal Reserve should be relieved of its dual mandate and focus instead on some range of commodity prices. Others go much further and wish to see the gold standard’s triumphant return in an epic “I told you so.” Each time someone proposes those or something different but of similar intent all aimed rightly for “stability” I am left wondering each time, “HOW?”

Typically (actually in all cases that I have found) the scheme involves no awareness of how money actually operates in the 21st century. How does one impose a gold standard in the setting, for example, of a cross currency basis swap? I am not even considering the difficulties of trying to impose a price of gold among both sides of that transaction, rather how would the security actually function? Cash flows are exchanged, but would they be cash or gold? If the former, how would that be convertible into the latter? How we would figure out even in a ballpark estimate how much gold would be necessary to cover all potential liabilities arising from just the monetary obligations related to these swaps? It would be easy to say that you just banish all such complications and impose everything by sheer diktat, but that is not the world we live in (though that is why 2008 would have been the best time for these discussions). Considerations must be given for how to go from here to there, and that space in between is a quagmire of unthinkable complexities.

Raising these questions doesn’t mean that I disfavor a gold standard or hard money, only that it would be far more complicated than most who propose this route make it seem. If you are simply replacing gold reserves for bank reserves that is one thing, but as we know very well from the eurodollar perspective the global money system is far, far more than that. A credit-based reserve currency brings up all the ways in which banks “manufacture” this credit as money.

Given that, I do think it points us in one direction of where this all could or even might begin. Among the first tasks of whatever reform program develops would be to scrap the Basel framework in total. Not only is it ill-suited to its task, it has actually become a perversion of that task. Capital ratios can be an effective means for analyzing a bank’s strengths or weaknesses, but in a regime where capital ratios determine everything they are instead the pathway to manipulation and distortion. The whole point is undermined by its own setup.

In broad terms, the Basel regime meant to define a bank by its assets. That was the idea behind “risk buckets” where those were thought an easy glance to determine what a bank was doing and whether it warranted any concern. What actually happened was quite different, disastrously so. Regulations designed to help the public determine easy comparison to other banks instead was used by banks to hide their riskiness as if they weren’t being risky at all (subprime mortgage structures rated AAA that were given favorable RWA treatment, and thus were made to seem low risk when nobody actually knew any of the risks). Insane complexity further obscured what was thought a straight-forward design.

Manipulated capital ratios including off-balance sheet accounting gave the impression of official sanction of some very dubious behavior. Some banks got into some of the worst ideas, but because their capital ratios were barely affected (because they knew very well how to accomplish this; CDS comes immediately to mind) it was if they had received state approval for being, frankly, dumb.

Banks are always going to do dumb things, and do so in ways in the future we cannot conceive of at this moment. The issue isn’t their assets, it is what happens when their assets are revealed for what they are – the age old question of money and multiplication. The Basel rules were developed precisely because of the “missing money” 1970’s; in other words, because banks were funding their operations in new ways that regulators just didn’t understand or, in the specific case of the Fed, didn’t want to, it was believed that in this brave new world of new banking/funding money was no longer an integral part of evaluation.

In our history up until the early 1980’s, bank regulations concerned the liability side much more so than the asset side. Funding was the mandate because that is what this is all about from both sides, a fact reinforced by the experience of the 1930’s. With new more pliable “money” no longer attached to either gold or even cash (eurodollars instead are not a physical thing) it was simply thought that bank runs were no longer a legitimate concern. If a bank got itself into funding difficulties, there were any number of ways for that to be resolved; and thus there was no way it would ever become systemic especially with capital ratios illuminating all risks.

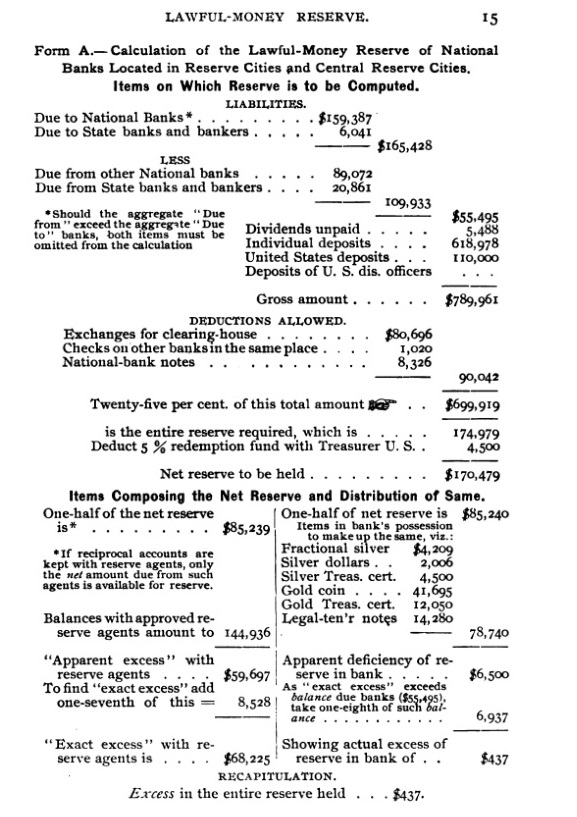

While it was expected that a modern, global money market would solve funding matters for both regulations and bank practices, in truth there were definable differences that were extremely important. In his Hand-book for Bank Officers, George M. Coffin in several additions in the 1890’s makes plain the role of money and even begins to appreciate the evolutionary shifts in banking monetarism. It details concepts and offers example calculations for bank managers in determining regulatory concurrence, including and especially reserve requirements. The concept of liquidity is often thought to be a modern convention, and in many ways it is in how it has spread, but there is no doubt that banking even in the late 19th century had become well-aware of more complex fluidity.

Even though there were several forms of acceptable holdings, bank reserves are what mattered the most. In a traditional fractional reserve setting, the reasons are obvious. On the right side (above at the bottom) are balances of actual money; on the left are balances of private correspondences with other banks held in the purpose of the necessary payment system that had developed in the late 19th century. If there was money on the right, there was on the left the ability to obtain it from somebody else; an ability that was acceptable as reserves for regulatory as well as functional reasons.

Changing to a modern wholesale format, however, doesn’t alleviate these obligations, it merely transferred them further out. In other words, where deposits of hard money formed the basis for traditional banking, the wholesale system itself has the same concept of a basis but one that is almost always undefined, perhaps undefinable. Bank examiners using Coffin’s handbook could easily understand the monetary sufficiency of any bank, at least in what would be normal conditions with some margin for heavier withdrawals; in the modern setting nobody had any idea because “dollars” were thought available theoretically ad infinitum in “the market” – especially with the Fed through its interest rate target supposedly standing behind that market. The right side of Coffin’s ledger simply disappeared, leaving not just what was on the left side but innumerable new ways to function within it.

But what was easily understood in Coffin’s day about how a bank in trouble might obtain relief, there was no such understanding in the eurodollar system. It had always seemed to be limitless, so it was just assumed to be always limitless. With nobody watching this sublimely fungible system as it expanded in ways that were (and, again, will be) unimaginable, there was no way to tell even from among banks themselves what to do should “the market” for “dollars” suddenly be less reliable.

In short, a traditional deposit account was a derivative though direct claim upon what was in the bank’s vault; the new interbank regimes, pre- and post-Federal Reserve, might be that (right side of Coffin’s ledger) or might be one further step removed (left side of Coffin’s ledger); a claim on what was in the bank’s vault or what the bank could claim from some other bank’s vault through the interbank system. With that line of trajectory established, monetary evolution simply progressed further and further away all in the name of efficiency and elasticity, based on untested assumptions cemented by recency bias.

What passes for money now is whatever liability one bank offers to another on acceptable terms for both. Nobody will know what that is except those two banks. That was both the main driver of the eurodollar system in its rapid growth and acceptance as well as its fatal flaw. Any of the major failures in 2008, from Bear to AIG to Lehman, can all be described as traditional bank runs but not in the sense of deposits or depositors; what was being claimed and removed from those doomed firms was not money from their vaults, but little indescribable pieces that though they were virtual and ephemeral somehow could not be replaced. In the easier to understand example of AIG, what they ran short of was not Federal Reserve Notes (or even a “too low” capital ratio) but unencumbered collateral. And what made all the difference was not figuring out how much, but more so why.

Because nobody was watching “dollars” and hadn’t been for decades, the ways in which this “run” propagated was unappreciated. The consequences were devastating, as they had always been before – bank runs typically preceded depressions. And they did so because they often damaged the foundations of banking and money such that the economy could not emerge unscathed. This time was no different even if the “run” itself was entirely different to experience.

The Basel Banking Pillars justified the ignorance of wholesale money and its dramatic evolution all over the liability side; and it was done out of expedience more than anything else. Again, regulators well aware of what the “missing money” 1970’s would mean in complicating their tasks, as we need to keep in mind that bank failures became more common during the 1970’s and then the S&L’s of the 1980’s that mostly failed on new money rather than actual money. Simply taking the shortcut of switching to the asset side, as if that would solve their problem, compounded it for the long run in which we now inhabit.

I fully believe that as one of the first steps in restoring money and really monetary sanity would be to take the challenge head-on rather than to continue to deny complex reality. Scrap Basel and refocus on liabilities. Basel III attempts a mild approach with pieces like the LCR and leverage ratios, but these are half measures at best that were developed specifically to fight the last war (2008) when the “next one” isn’t likely to be at all similar. Even in decay, the eurodollar doesn’t stand so still.

The goal is to understand modern money instead of just making inappropriate blanket assumptions about it. In my view, it makes no sense to agitate for gold or a commodity-stabilized dollar without first understanding what it would take to realistically achieve them, or even if it is possible.

Stay In Touch