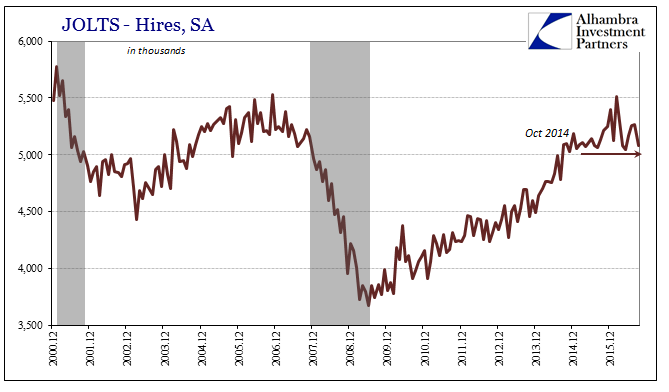

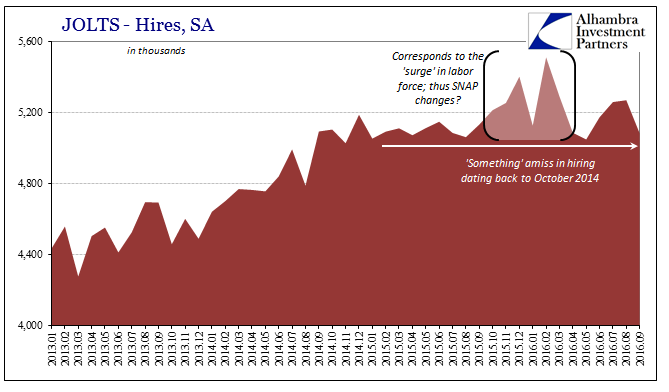

The BLS reported that the rate of hiring in the US continues to be sluggish and sideways. Total hiring across the labor market was estimated to be 5.08 million (SA) in September, down from August and the second slowest rate this year. Since first surpassing 5 million back in September 2014, the overall pace of employer engagement has been largely stuck (excluding what is surely SNAP related changes in work requirements filtering into the JOLTS set via its CES benchmarking). Despite the passage of two years and the population growth during them, hiring conspicuously remains at the same level, meaning yet again contraction though positive numbers.

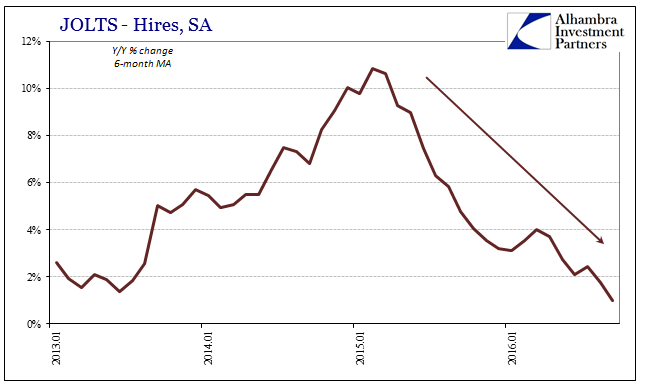

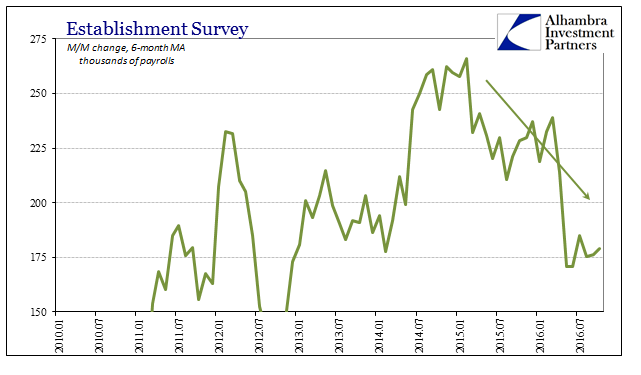

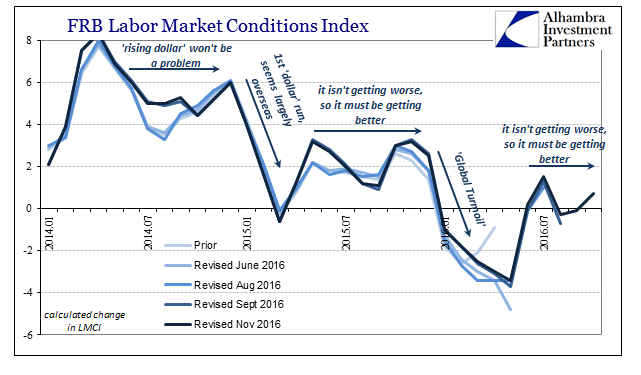

It is, of course, the exact same trend that we find in countless other statistics, including those of the main payroll reports. Converting Hires to a year-over-year comparison, the outline of the Establishment Survey, LMCI, and a number of others is obvious within it.

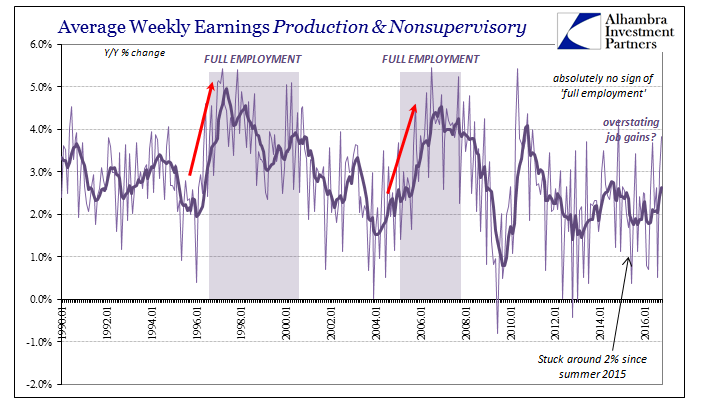

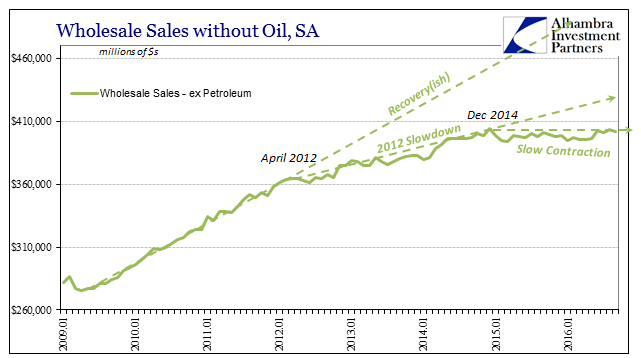

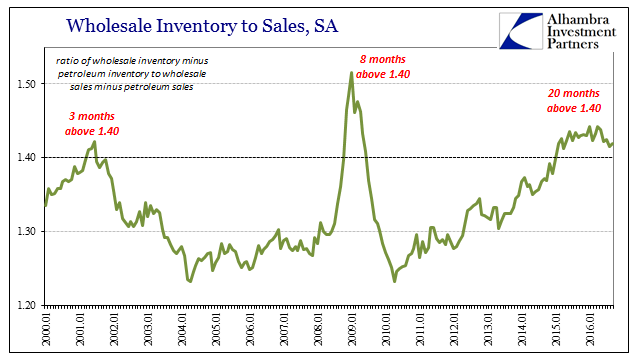

Less hiring would suggest fewer overall new jobs and therefore despite a historically low unemployment rate very little as far as wage and income gains. That would all certainly account for a further slowdown in spending, as well as the related rise in inventories that was surely predicated on a view of the labor market based on the unemployment rate rather than what the rest of the labor statistics have suggested all along.

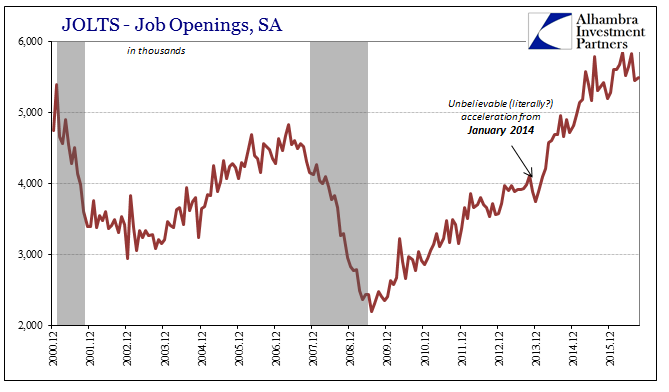

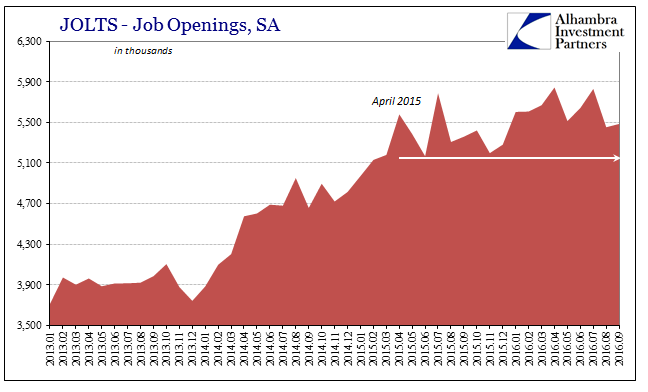

This weak, sideways condition can even be found in the Job Openings data series, one which despite being unconnected with anythi7g on the way up, especially Hires, has at least run into the same wall of slow.

As I wrote last Friday with the release of the latest payroll report:

You can easily understand their mistake, though not condoning or forgiving it. In those previous business cycles where the unemployment rate had fallen similarly low, wages and earnings had surged, thus confirming the orthodox concept of “slack.” As it disappears in the normal course of a healthy economy actually growing, employers must bid up for employees as there are fewer sitting home; basic economics (small “e”). There is absolutely none of that now, not even the slightest hint. The reason is that the unemployment rate in this economic condition applies only to a much narrower proportion. The participation problem is real, and it is one that policymakers should not have so easily dismissed based on dubious statistics.

Putting that in terms of JOLTS, misreading the economy of 2014 led economists to expect that both Hires and Job Openings would continue to surge without ever questioning, as they should have, how far out of alignment they already were that year with everything including wages and income. But even those discrepancies aside, as the unemployment rate fell even further in 2015, neither of the JOLTS categories corroborated the descent, making pronouncements about “slack”, and therefore the entire basis for “rate hikes”, incredibly bad analysis. Economists were basing their expectations for “transitory” weakness on numbers that at the very start faced serious internal contradictions.

Those unbacked predictions grounded in the unemployment rate were pure hope rather than solid interpretation, a fact revealed by the ongoing economic struggle that this year has changed everything. What happens when an economy that isn’t growing anywhere near fast enough suddenly stops growing altogether? The typical answer might have been in the past “recession”, but that isn’t what we see here or anywhere. Instead, it is an economy, verified by a great deal of BLS data apart from the unemployment rate, that keeps getting weaker for each and every monetary disruption – the “rising dollar” being so far the last one.

What is truly frustrating is that the eurodollar change was picked up almost immediately in these statistics. It was incoming data confirming a plethora of market prices and indications that long before the summer of 2014 had been expecting just this kind of flagging economic fortune the US and global economy could ill-afford. Maybe that is why economists were so adamant about ignoring these possibilities, as perhaps on some level they knew that it would have meant the last straw.

Because of that, however, it really should be their final act. If there is to be anything that is to change, it should be removal of all those who have already shown themselves incapable of honest inquiry and analysis. Janet Yellen and her FOMC still refer to “transitory” weakness when even the BLS numbers don’t agree across several series of them. We just won’t be able to fix the global economic problem by swapping economists, as I wrote earlier today in light of the Trump win that has the potential for just such a possibility:

The Fed cannot simply be made to shuffle personnel, the equivalent of a wrist slap (proportional to the offenses) amounting to at most the sake of appearance. What good is a Janet Yellen resignation, assuming that one would be requested, when that would mean Stanley Fischer or any of the other dozen empty suits would take her place? Every single one of them would look at the eurodollar futures curve, for example, and say, as Bill Dudley has all over again, “that can’t be right because we are.”

In the end, as we can clearly see now, but was still quite evident then, all they ever had in their claim of being right about the economy and markets was the unemployment rate. But rather than clinging to it as a matter of even twisted but still rational analysis, policymakers used it like a young child does her baby blanket as a shield from unwanted negative emotions. It is/was disqualifying, and so what comes next has to be much more than letting Yellen quietly retire at the scheduled end of her term. She, as well as Bernanke and all the rest, must be made to account; starting with why she would mislead everyone based on so flimsy a pretense. As that inquiry would surely find, the 2014 “overheating” debacle is entirely too representative of how Economics operates.

Stay In Touch