One of the biggest intellectual impediments to understanding where we are in the arc of monetary evolution is Positive Economics. As Milton Friedman described it in 1953, it was essentially the doctrine of trying to explain a lot knowing very little. In such a simple description it sounds ridiculous, but in the reality of complex systems growing only more complex it is actually somewhat understandable (the limits of knowledge). Through correlations and regressions, econometrics sought to turn what was impossible to measure or even appreciate into control by making some very key assumptions about what parts or factors were most significant. Because Positive Economics did not and still does not seek to know the nuances and exact details of the variables it means with which to exercise control, much has been lost as far as understanding those variables as more than simple aggregates.

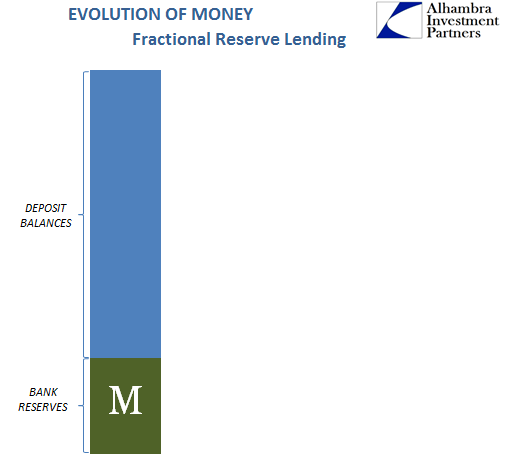

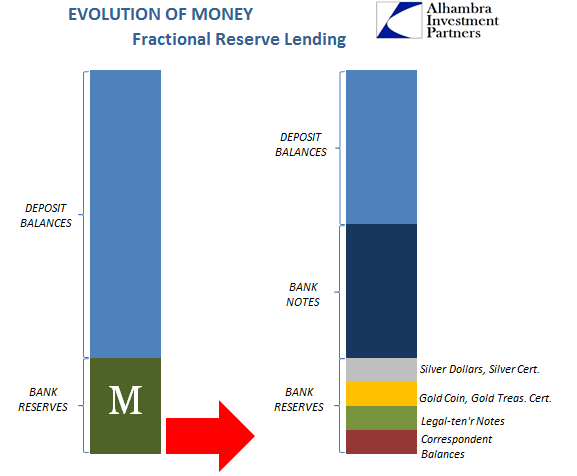

Almost everyone is familiar with fractional lending and the money multiplier; it is still taught in schools as the way in which the various forms of money are created and regulated. A bank holds some form of reserves from which it creates a multiple of deposits that act as derivative claims on that money. For the purposes of economic thought, there truly isn’t much if any thought given to the arrangement beyond that simple construction.

One of the primary benefits of researching monetary history without the anchor of orthodox economics is to be able to appreciate that the past wasn’t so bland as all that. It is an element of human nature to instill a kind of simpleness into nostalgia, to see the past through the lens of modern existence and to appreciate only what seems to be the vast differences. In monetary terms, there was a great deal of texture to that past, as well as its relationship with banks intent on those fractions of it.

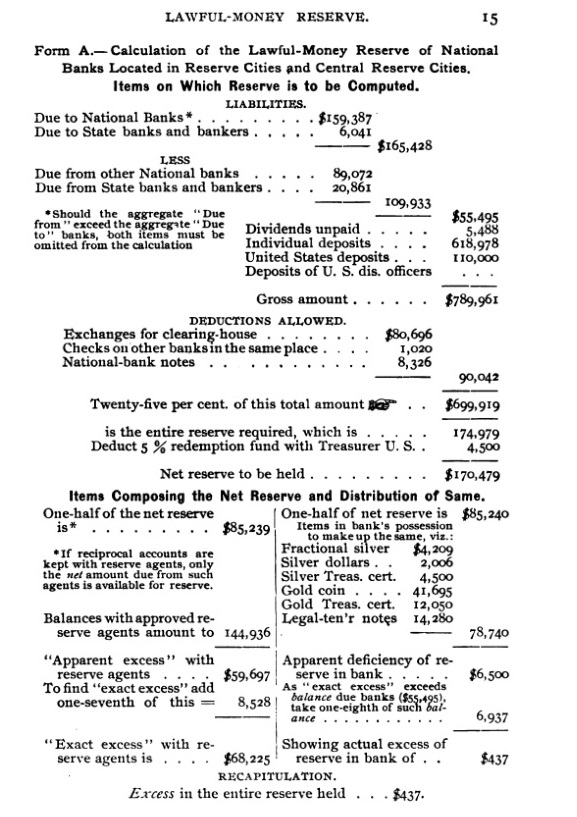

Reading through the various 1890’s editions of George Coffin’s handbooks for bank examinations gives you one means for taking greater appreciation for the subtleties and difficulties with what we think of now as primitive finance; it really wasn’t. Those judgments were added later in the “modern” lookback of post-Great Depression scholarship. There were then various forms of money as well as quite modern and complicated methods for handling it within the various banking structures.

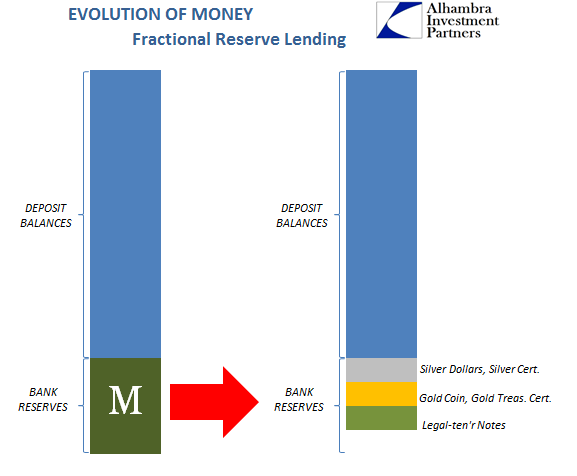

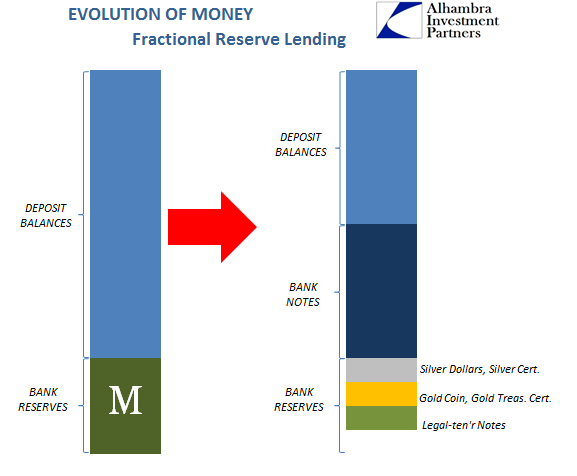

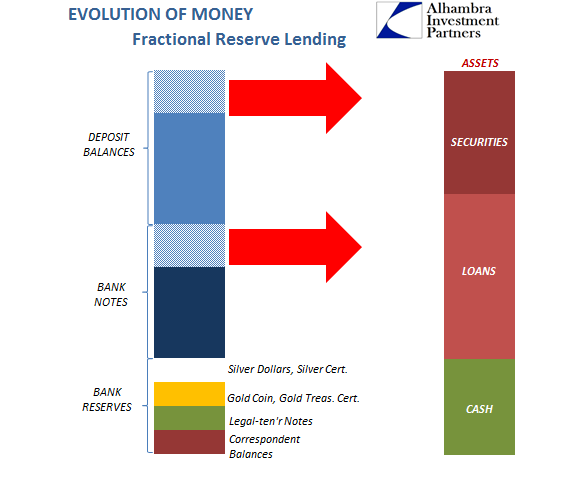

Not only did money itself take up several different forms, the multiplier action of banks was not itself monolithic, either. Thus, the monetary system of the pre-Fed era was robust in both money and its multiplications. It is difficult to conceive of now, but currency was on an individual basis, meaning that banks turned vault money, including US Treasury Notes, into both deposits and paper dollars.

But there was one more facet to the calculation of bank reserves that isn’t much appreciated because in operation it was a derivative claim on money, too. For regulatory was well as operational purposes, banks were allowed and did count correspondent balances as part of their reserve catalog.

These were deposit accounts that moved up the chain of the national payment system; a small country bank had to hold some balance at a reserve city bank in order to cover checks its customers might write and send beyond its operational borders. Correspondents also managed the flow of individual bank notes, which would be presented as a claim against the bank’s accounts should they have been spent again someplace else (usually at a discount to par, which is one reason there was an agitation for a national currency, which the founders of the Fed neatly folded into its founding purposes to give the institution a popular spin).

But correspondent balances were not actual reserves, as they were not actual money. Like bank notes or even deposit accounts, because they were, in fact deposit accounts, they were a derivative claim on money from someone else. That “someone else” just happened to be another bank, which for statutory reasons was assumed in better standing and capacity to be able to meet that derivative claim if called upon. Correspondent balances were often large, especially as they cycled up the payment system ladder to central reserve city banks (who made these “idle” deposit balances “efficient” by lending them out in street loans or call markets; i.e., Wall Street, linking money with asset speculation more directly).

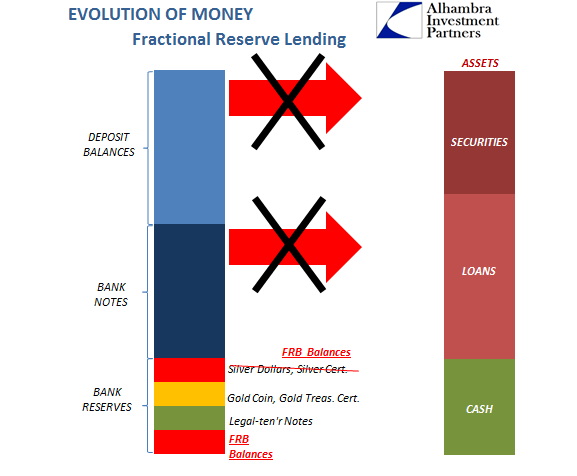

In its first decade of existence, the Federal Reserve by hook and by crook (it often used dirty tactics backed by its new regulatory authority to force individual banks to switch to the precursor Fedwire system) sought to compete with and then overthrow the private interbank correspondent system. But it was more than that, as the payment system was just the natural component of evolving economic life as the US economy moved beyond strict regional borders.

Bank panics had been a plague on the economy as it industrialized and gained distance from its agrarian, decentralized past. The Federal Reserve was heralded as the means to currency elasticity in the European sense (though that element was kept from the public skeptical of central banks in the European sense, which is why there is a “Federal Reserve” rather than a “Central Bank of the United States”), which meant in an emergency the central bank could be the lender of last resort that kept the whole system liquid and any specific problems individual. This was quite different than the correspondent claims that only went in one direction.

As a rough, stylized example using the same setup as described above, say a bank experienced a run on its silver vault holdings. The sudden absence of that part of its reserves meant that the bank was forced into all manner of increasingly unpleasant choices by virtue of money multiplication in reverse. It would have to liquidate: call in and cancel some of its notes, shrinking the local currency supply, as well as deposit accounts, while simultaneously selling securities (if it held any) or more likely calling in loans (and forcing borrowers to liquidate their holdings). Because this process could never be self-contained, the interest of government authorities to try to head off any reverse money multiplication makes a great deal of sense as far as public interest (setting aside, of course, discussion as to whether shrinking banks at any such times might be, in fact, appropriate).

The Federal Reserve System because of its accounting meant that bank balances at FRB branches not only counted as reserves they were also malleable when needed. In other words, through various schemes unlike correspondent balances banks could increase their reserves by discounting assets (bonds or acceptances) in lieu of lower levels of vault money withdrawn by depositors exercising convertibility. In our simple example above, it would have meant that a bank losing all its silver could have just replaced it with what were classified then, as now, as “borrowed reserves”, providing that bank had sufficient collateral with which to place for discount at its local FRB branch.

So long as the bank could survive any acute withdrawal, that bank would then be able to avoid all the systemic, harmful actions that had in the past turned negative money holdings into a multiplied, spreading financial contagion, and then systemic contraction.

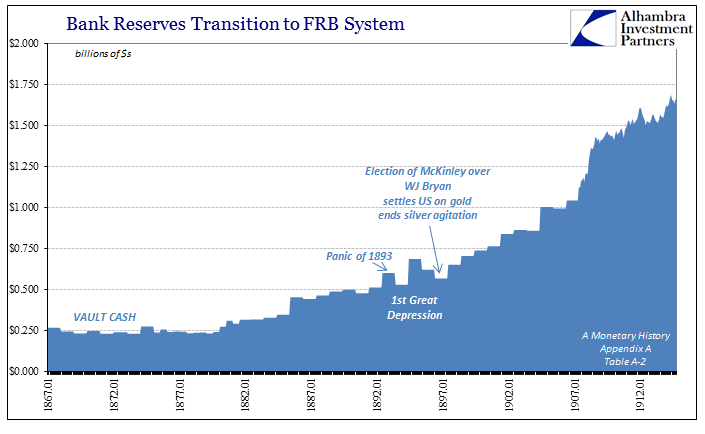

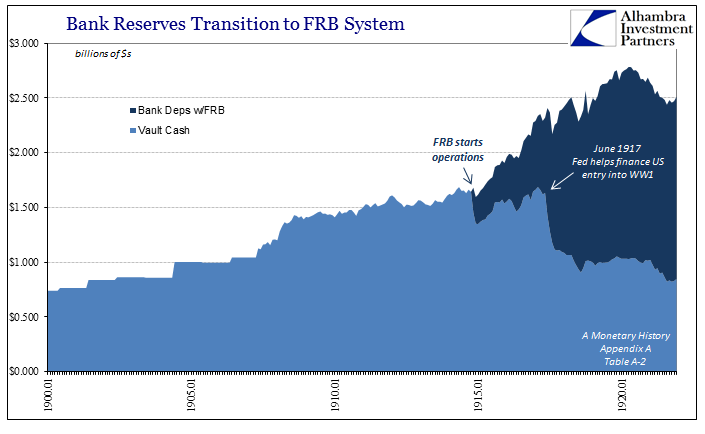

This very process was tested almost immediately after the Fed’s founding by the US entry into World War I. Bank reserves of various forms of vault cash had been rising throughout the second half of the 19th century, but especially so once silver agitation had been put completely to rest with the 1896 election of William McKinley (gold mono-metalism) over William Jennings Bryan (silver populism). NOTE: the figures for bank reserves are taken from Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s 1963 book A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960.

The Federal Reserve became operational in later 1914, with the first redistribution of bank reserves that November just in time for WWI in Europe (ending the traditional gold standard era). In June 1917, Section 16 of the Federal Reserve Act that had required all Federal Reserve Notes (the national paper currency) to be backed 100% by real bills, with an additional restriction of 40% backed by gold held by the Fed, was relaxed. Section 13.8 was changed so that the US central bank could make loans to member banks with government bonds as collateral (and further being freed from the “real bills” restrictions as pertaining to these 13.8 loans).

The idea was to get the Fed to help in financing the US war effort. In terms of purely banking, the massive sale of Liberty Bonds to the public and their actual eagerness for them had the effect of stripping money from bank vaults in exactly the manner of our “silver run” example from above. The response was a replacement of vault cash held by banks with FRB balances exactly as I described.

Where banks were depleted by an enormous outflow of vault cash into Liberty Bonds, a 45% decline by August 1918, according to Friedman and Schwartz, a reduction of almost $730 million, in general outline bank reserves as a whole exploded instead and the US economy resulted in latent inflation rather than immediate deflation. Banks were not forced into liquidations by a massive monetary drain, purportedly proving the FRB concept.

This is quantitative easing in practice, only without the “Q.” The central bank controls the amount of bank reserves independent of the actual quantity of money in bank vaults or in circulation. In this situation, banks were freed from liquidation pressures and indeed can have been “overstimulated” into some serious inflation rather than having been sunk into monetary shortage, bank panic, deflation, and then the usual depression. It wasn’t until 1920 that all those occurred, but then as an intentional matter of monetary policy to undo some of what was done by war “necessity.”

Being still nominally dedicated to real bills and thus sensitive to big changes in wholesale prices, the Fed sought to reduce the monetary error beginning in early 1920, resulting in deflation and depression with FRB balances being withdrawn without vault cash returning to their pre-war levels. Thus, what was established for those who looked favorably upon activism was demonstrated control in both directions. Bank reserves acted as an aggregate.

Part 2 is here.

Stay In Touch