Rumors persisted in China of new foreign currency restrictions from state authorities now trying to crack down on corporate activity. The story was picked up in many news outlets all over the world, but will remain unconfirmed as it is based on reports from the South China Morning Post and others inside the country that have only claimed to have seen the official government memo dated November 26. Official sensors, it has also been reported, have been busy scrubbing the allegations from the Chinese internet, which only further serves to add credence to the rumors.

For its part, Chinese officials in the Foreign Exchange office (SAFE) issued a “terse” three-line statement vowing to crackdown on what they see as “fake” M&A activity meant to disguise capital outflows. This is a reverse of longstanding rules that were meant for better times when the Chinese were under the opposite constraints, longing, apparently, for the days of being a prime “hot money” destination.

In describing this possible, unconfirmed change in rules, the South China Morning Post quotes a local analyst who describes the overview but with the usual missing nuance:

“The logic behind the new measure is to drain offshore yuan liquidity because too many people are exporting yuan for currency swaps or for shorting the currency as a way of skirting domestic restrictions,” said Li Yimin, senior analyst at Shenwan Hongyuan Securities. “Previous controls were mainly aimed at controlling the yuan’s inflows to deter hot money. This time, the focus is on its outflows.”

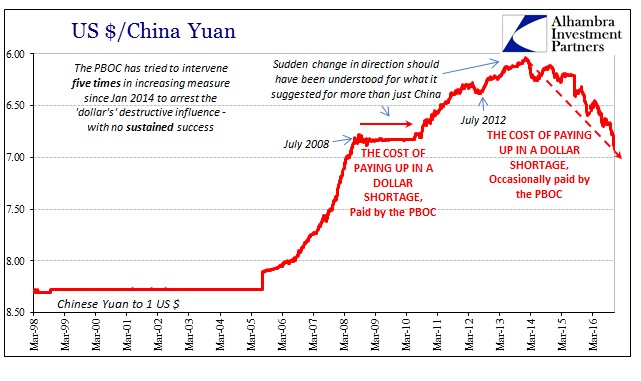

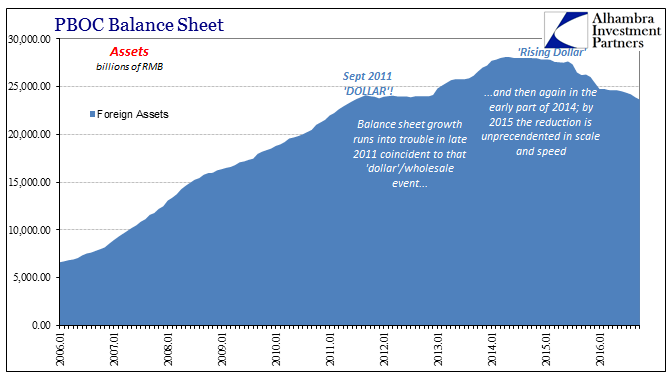

It is interesting that Li mentions “exporting yuan for currency swaps” into the offshore market, because that is where the problem first manifests – though not strictly for yuan. One look at the long-term CNY chart reveals the full picture, as to when “dollars” were plentiful as backing all sorts of RMB claims and uses (“hot money”) and the clear shift to where “dollars” were not, now requiring increasing effort just to maintain what there is now.

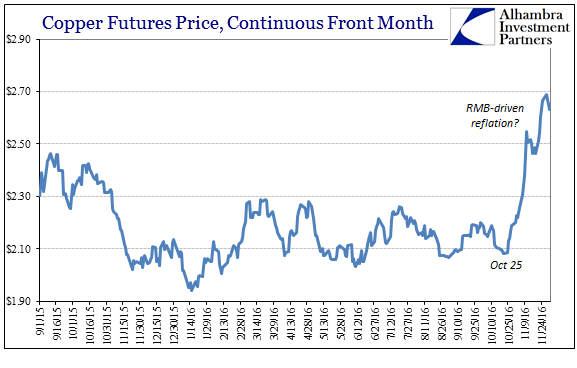

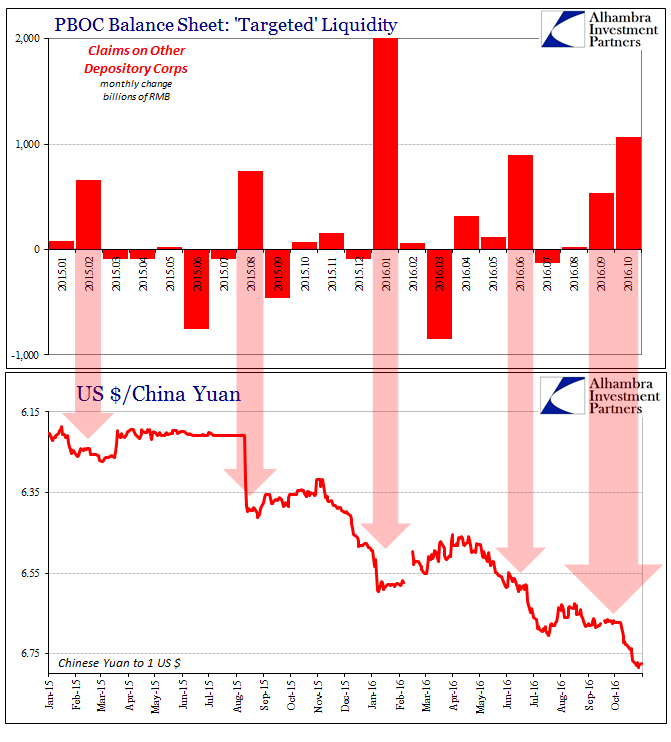

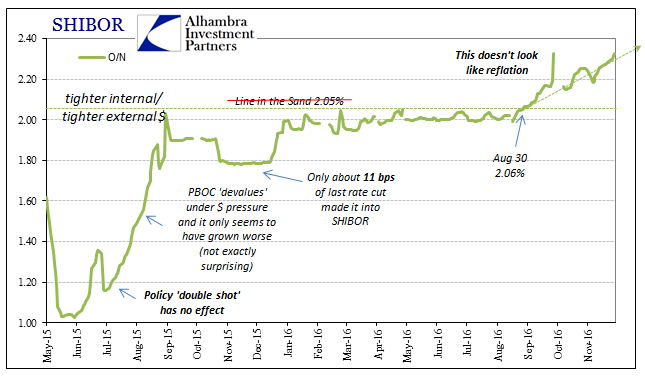

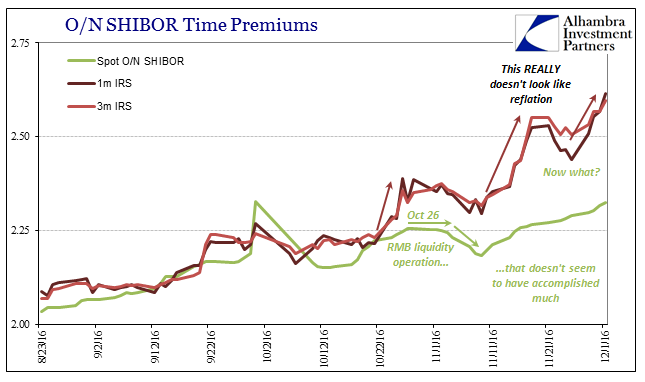

This ramped up “effort” aimed at what is traditionally viewed as “capital outflows” manifests in several ways, but most prominently as a drain on internal RMB liquidity. Thus, it has been something of a rule of thumb where we can discern the relative level of China’s “dollar” problem by how intensely the PBOC fights against it with RMB. To that end, I have suspected since late October that around October 25 the PBOC was forced into a serious liquidity regime of internal focus; so forceful that it acted like rocket fuel for copper while simultaneously spilling over negatively into Hong Kong proper (HKD).

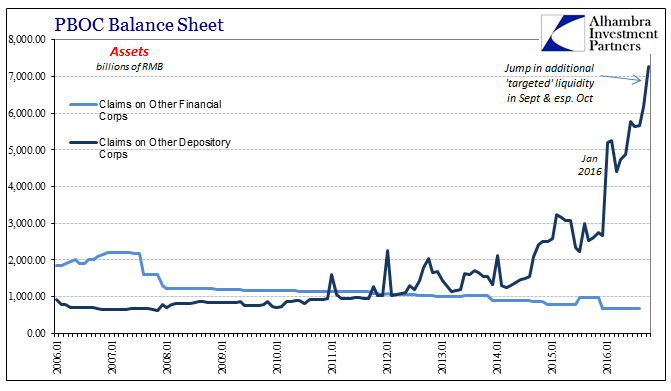

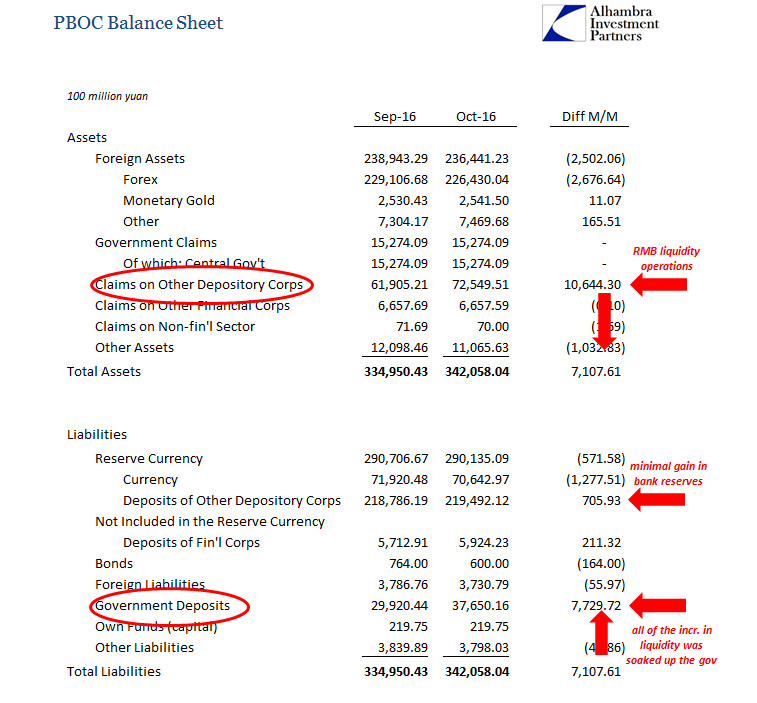

The PBOC statistics do, in fact, show a large RMB liquidity operation during October. They do not, of course, tell us anything about the timing of it, but given the actions in SHIBOR, HIBOR, and copper it does seem as if my suspicions were correct.

The total reported amount run through the MLF, SLF, and whatever else Claims on Other Depository Corps was nearly RMB 1.1 trillion. That was just about double the net operational size as in September and the largest since January when everything was going wrong everywhere.

Without that RMB intervention, the PBOC’s asset side of the balance sheet would have shrunk in size again, as its forex basis declined by RMB 250 billion, down RMB 1.7 trillion since the end of last year.

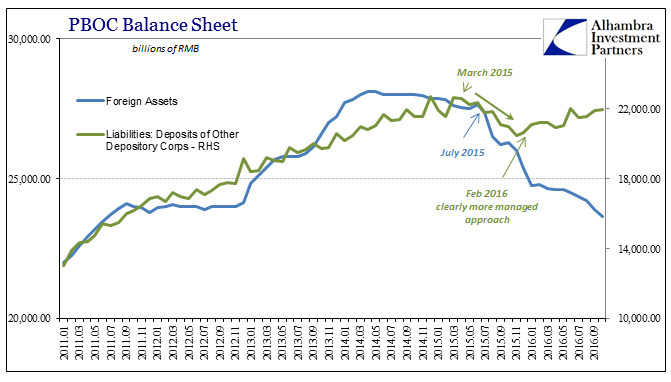

You can see the difference this year versus last, where the PBOC simply allowed monetary shrinkage internally due to the “dollar” (again, what is referred to in the mainstream as “capital outflows”) to directly and proportionally affect internal RMB bank reserves (money). As noted above, since January the Chinese central bank has been quite active during months of heaviest “dollar” pressure so as to try to reduce as much as it can its negative effects upon the Chinese system internally.

But China under these circumstances is a tangled web of contradictions, as we can easily observe by the state of its money markets and of those around it. In the month of October, despite the large RMB liquidity operations, the increase in overall bank reserves was far more modest, minimal even. The reason was the usual drain on liquidity from government deposits.

From this you can appreciate the PBOC’s dilemma and why it as part of the overall government structure would seek to alleviate its “dollar” pressure through even “capital controls” that aren’t what they might seem to be. To give the Chinese system full availability of RMB (which in October would have meant RMB 2 trillion, RMB 4 trillion?) risks turning China’s markets into copper, where an imbalance in real estate and other asset classes are already at the top of the official list for deflating (which is, I believe, one reason the PBOC in RMB sat out the monetary contraction of 2015). And in the case of October 2016, what they did do in size was just enough to keep the overall system from contracting due to seasonal factors of government influence.

That is why, I think, SHIBOR rates diverged from copper, especially since the “targeted” liquidity of Claims on Other Depository Corporations is channeled directly through China Development Bank and other state-owned behemoths like it. The general interbank market for RMB, on the other hand, was left with the effects of the government drain, leaving the PBOC’s overall addition not strictly as an addition, but rather a redistribution of RMB. This proves yet again that actual central bank programs are not so straight forward as they might ever appear to be, and that currency elasticity as a theory does not fit the real world mechanics of how things actually work.

And so it leaves with perhaps a perfect representation of this year’s global dichotomy, the same that I have been writing about for months. Clearly markets like industrial commodities, not just copper, appear to be a reflection of relation expectations particularly linked to a China which monetarily isn’t as contractionary as it was last year. There is great hope in that being quite “different”, but while the PBOC is doing some things, sometimes in size, in order to counteract the negative “dollar” pull on its balance sheet, on the other side, the more important side of actual condition, is what we see in October, where what the PBOC actually does isn’t really all that different especially in its effects.

Thus, we have this diverging situation where certain markets see great things of reflation ahead even though money markets themselves remain “somehow” are left in a state of turmoil and even growing chaos. The central bank looks like it is doing something different, but in the end it really isn’t able to.

Stay In Touch