Last summer was perhaps the most pivotal period of the past two years for the economy in a number of ways. It was that moment stuck in between what was supposed to be, even if acceleration and liftoff were delayed by the “rising dollar” of late 2014, and, of course, what has become accepted that it never will. Less than a month before the Chinese would stun the world with their huge “dollar” problem, Janet Yellen told Congress that there was nothing much to worry about.

It was all pretty much standard stuff by that time, mostly concerning how the robust labor market would act as a more than sufficient cushion “should” any “overseas” troubles come our way. In her prepared remarks last July, Yellen said:

Looking forward, prospects are favorable for further improvement in the U.S. labor market and the economy more broadly. Low oil prices and ongoing employment gains should continue to bolster consumer spending, financial conditions generally remain supportive of growth, and the highly accommodative monetary policies abroad should work to strengthen global growth.

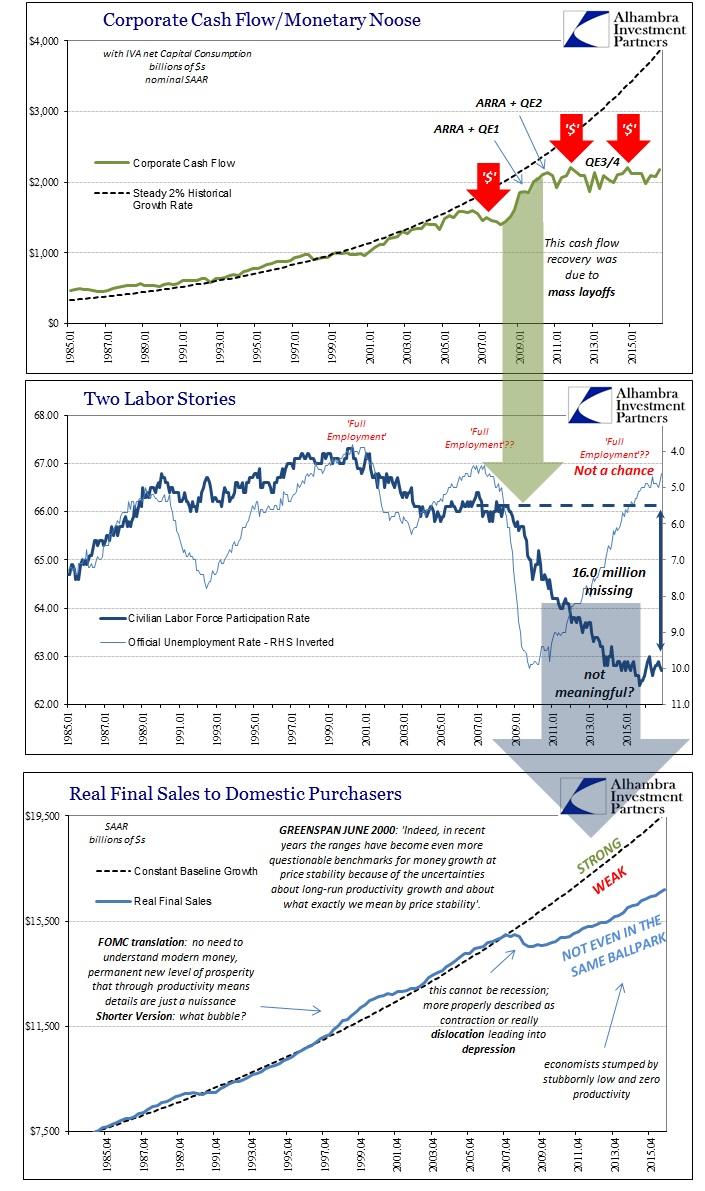

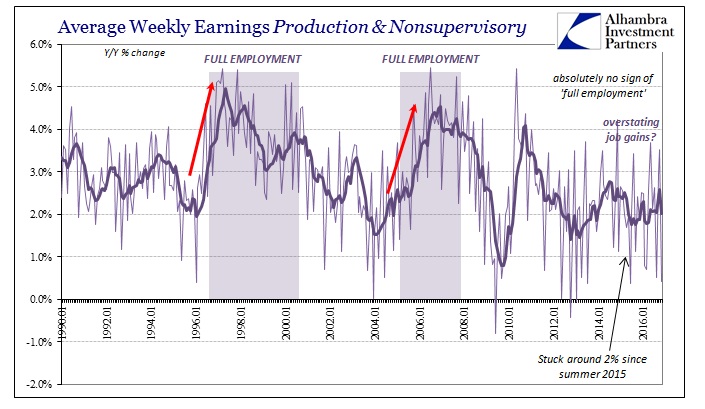

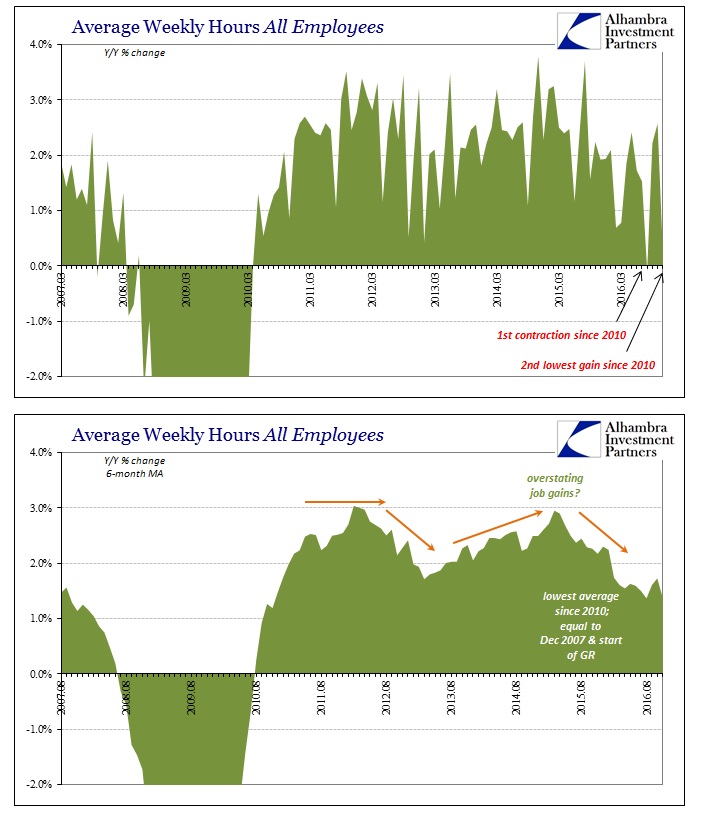

Of everything on her list in that passage, none of it actually happened. You can make the case the labor market at least by the view of the unemployment rate has improved, but as 2016 winds down that statistic is now even more isolated that it was in the middle of last year – even the Establishment Survey registers significant slowing.

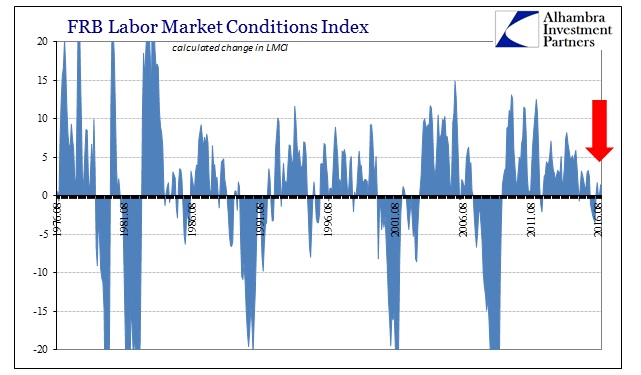

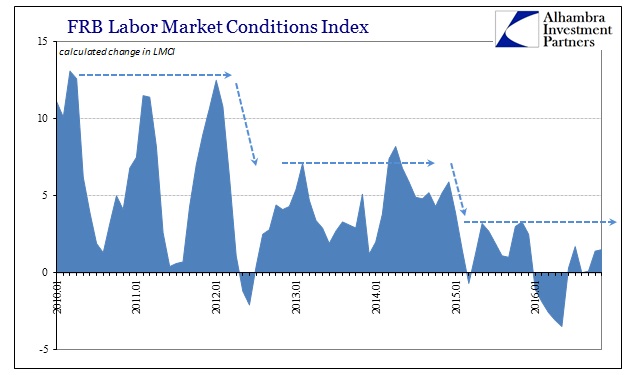

The labor figures more broadly aren’t actually so ambiguous, nor were they when she spoke to Congress last July. For one, the Federal Reserve’s own Labor Market Conditions Index (LMCI) had already displayed what should have been taken as a massive warning. It had been as high as 8.2 in April 2014, decelerating moderately into the end of the year before falling off a cliff in January 2015. By March 2015, the estimate was negative.

The question Janet Yellen needs to be asked is why that sudden shift didn’t cause any re-evaluation on the part of the Fed. We know part of the answer was/is credibility, as it was clear then that the FOMC was determined to act throughout 2015 after making such a positive fuss at the end of 2014. The LMCI was developed specifically due to the problem of the unemployment rate, meaning that though Fed officials speak positively about it they know full well the problems in the denominator (which they downplay as at most the demographics of retirement).

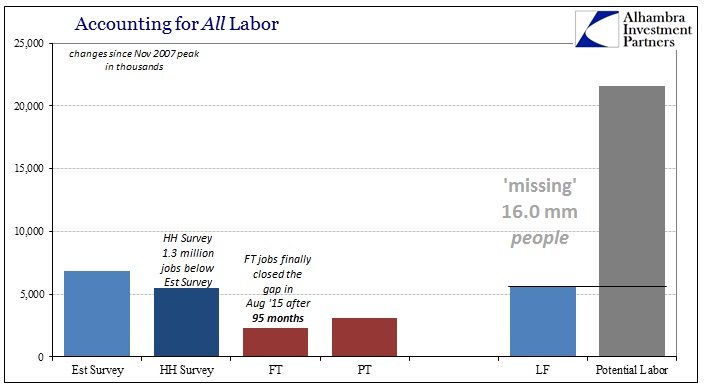

The numbers the LMCI has sought to provide additional “color” for are astounding. Since the past “cycle” peak in November 2007, the eligible pool of potential labor (civilian non-institutional population) has grown by 21.6 million. Yet, the actual labor force, or what the BLS has decided counts as the actual labor force, has grown by only 5.6 million – leaving 16 million stuck nowhere. They are outside both the unemployment rate as well as the economy.

What has been less clear, at least for economists, in terms of common sense there is nor has there been any doubt, is what possible effects those “missing” 16 million might have had upon economic function. If the participation problem were shown to have been a significant drag, that would have had implications for a great many factors, including inflation due to the economy inching prospectively closer to full employment. From the raw perspective of the full labor pool, it would seem as if the 16 million “missing” constitutes a great deal of “slack” and thereby a great deal of economic deficiency left over from the Great “Recession” which should be considered in both economic forecasting as well as monetary policy settings.

From the view of the unemployment rate, however, if Baby Boomer retirement was/is truly the issue, then policymakers could be more confident in their positive economic pronouncements. The purpose of the LMCI was to offer a different perspective from which to help determine which side the economy was falling.

The problem for Janet Yellen and not just in July 2015 was that the LMCI was confirming her opposite case. Again, there were a great many economic accounts that by last summer had already suggested serious weakness, especially those related to consumers. From imports to manufacturing to sales, retail, wholesale, and otherwise, there wasn’t much if anything to suggest that the unemployment rate or Establishment Survey had it right. Then the LMCI, which was meant to help decide the issue, looked almost exactly like those other accounts rather than the mainstream interpretation of the whole economy through the headline BLS numbers.

A wider perspective of it shows plainly the pattern economists have been trying hard not to see. It is the same exact outline of the economy that we find in other US accounts, as well as those from all over the world.

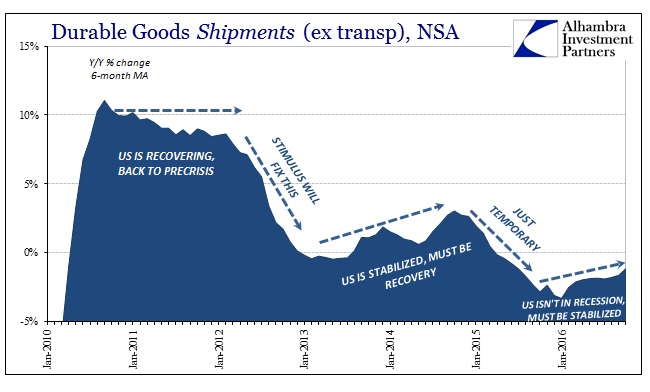

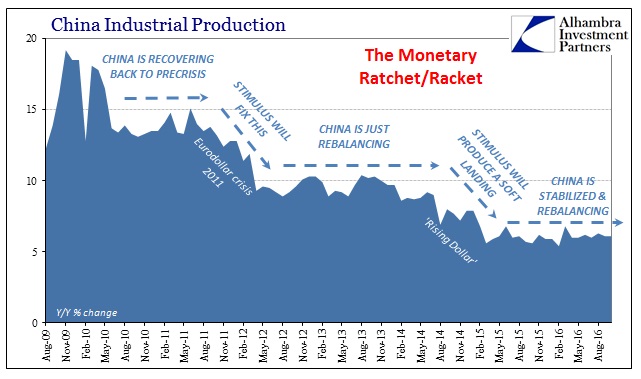

There is, perhaps, the impression that economic data especially in the past few years has been “mixed”, meaning that there isn’t or wasn’t a clear indication among a majority of statistics where the economy was actually heading. That just wasn’t true; among the non-payroll stats the trajectory was perfectly clear and for more than just since the second half of 2014.

The three data points presented above are all derived from vastly different data sets by collected and put together by different agencies (in the case of Chinese IP, obviously, from a different government), yet they present the same economic picture going back to the stunted start of the “recovery.” The near exact replication among them, including and especially timing, leaves little doubt that they together offer a more realistic assessment of the economy at each point along the way; as well as tell us a great deal about what the future may look like (a distinct absence of “reflation”).

That the Fed’s own LMCI is included in that corroboration makes Janet Yellen’s words to Congress, as well as to other audiences, meaning the public in general, highly suspect. Again, the LMCI was put together in August 2014 so that Fed officials would not become too infatuated with the main payroll numbers. That they did anyway despite the LMCI offers very troubling evidence that policymakers and economists (redundant) were never “data dependent” and were instead emotionally invested in an outcome that by their own actual data had become increasingly doubtful.

Rather than confirm the unemployment rate, the LMCI actually helped verify the opposite case (weakness wasn’t “transitory”) including its relationship to the two main “dollar” events (both 2011 & the “rising dollar”). In the year since her testimony, the rest of the labor statistics have fallen further on that line (weak) and more so still against the idea of “full employment.” The BLS’s Index of Total Weekly Hours gained just 0.3% in November 2016, the second worst monthly number since 2010, the worst being the contraction in hours estimated in August. Meanwhile, total earnings, which includes hours as a component, disappointed again in November and continue to suggest full employment is as elusive as official objectivity.

If the economic weakness that began 2015 was isolated in terms of its reach as well as a limited to a single occurrence, then perhaps Yellen might be forgiven for what in hindsight was clearly absurd and desperate faith (it was no less ridiculous in real-time, but the past year and a half really has not been kind to her predictions). That was, however, just never the case, where even the Fed’s LMCI undermined its own claim to being “data dependent”; they clearly weren’t then, and it is perfectly clear they still aren’t now.

Should the FOMC “hike” in December, it will again have nothing to do with economy or recovery.

Stay In Touch