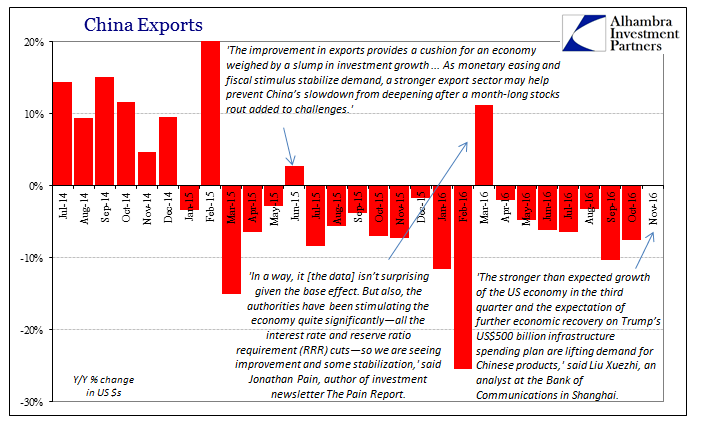

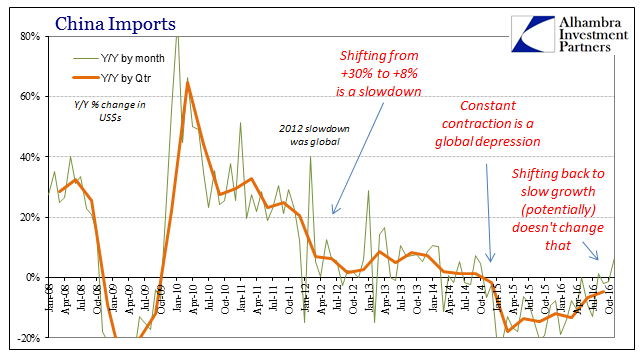

China’s trade statistics were improved in November, further fueling the global “reflation” dreams. Imports rose 6.7% year-over-year, the second increase in the past four months (August) and the best since September 2014. Exports were nearly flat, up the tiniest fraction, 0.1%. That was the second time this year exports were positive. Again, these numbers have been very well received:

“The stronger than expected growth of the US economy in the third quarter and the expectation of further economic recovery on Trump’s US$500 billion infrastructure spending plan are lifting demand for Chinese products,” said Liu Xuezhi, an analyst at the Bank of Communications in Shanghai.

The problem is both that these sorts of numbers are always very well received and aren’t as unusual as they may have been made to appear. There truly isn’t much difference between import growth of 0.4% as was first reported for May 2016 (since revised to -0.1%) and 6.7%. The two months that followed May’s initial positive number saw first a 9% decline and then one of 13%. Each time this happens, however, the optimistic number is extrapolated in isolation into full-blown growth when instead it should have been appreciated in the full context of continued and certainly continuing unevenness.

That is also true for China’s export side, where similarly pronouncements were made in mid-July 2015 when Chinese exports for the month before were figured to have also increased. Then, as now, a break out of the negative trend was expected. CNBC reported:

“The rise in China’s export growth was consistent with better exports elsewhere, such as Korea, suggesting that external demand may have improved. The smaller contraction in imports in June, despite lower commodity prices, points to a sequential improvement in domestic demand,” Yang Zhao, economist at Nomura wrote in a note.

For Bloomberg, the word “stabilize” made its regular appearance:

The improvement in exports provides a cushion for an economy weighed by a slump in investment growth that is putting Premier Li Keqiang’s 2015 growth target of about 7 percent at risk. As monetary easing and fiscal stimulus stabilize demand, a stronger export sector may help prevent China’s slowdown from deepening after a month-long stocks rout added to challenges.

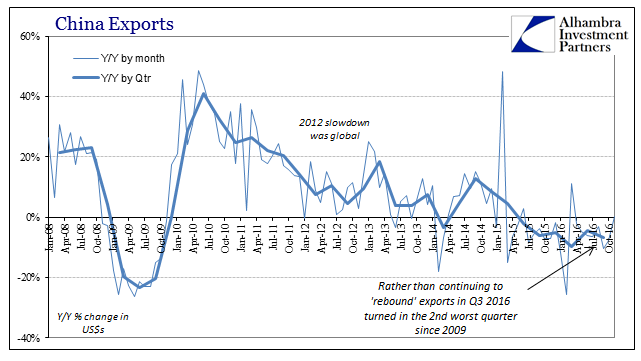

The very next month, exports fell by 8.4%, and then in each of the next four months after until December 2015 when they were published as nearly flat and restarted the “stabilizing” narrative all over again. The most egregious example of bias was for exports in March 2016, which were +11.5%. The -25% for February was just set aside, as the world for March seemed so much kinder in economic terms. It really wasn’t, as I wrote then.

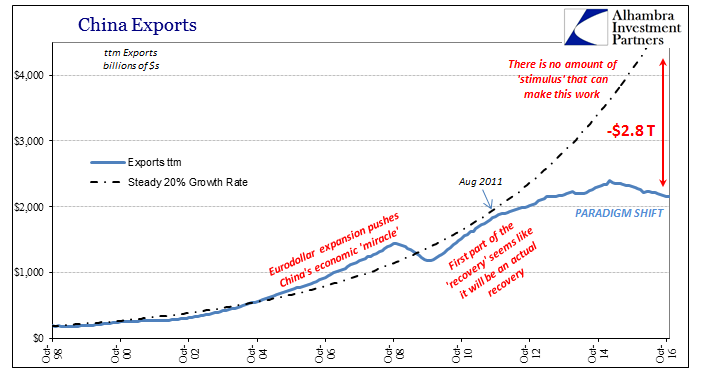

Even if there was improvement in March 2016, that is only in a small and largely irrelevant comparison. As I write month after month, China’s industrial economy was built to service rapid growth not variable shrinking. Despite that 11.5% gain over March 2015, the export total was still an enormous 11.5% below total exports of March 2013. It is a matter of volume (especially dollar volume) as well as time. The Chinese economic baseline and capacity (including capex and investment) is predicated on 20-30% expansion consistently, not 11.5% above last year which was 15% below the year before that. That trend isn’t growth but uneven, durable contraction.

This trend clearly remains to close out 2016. Some months feel good in a minor sort of way, while others, the majority, sink back to the reality of what this is. The global economy of the “rising dollar” has never been straight contraction, which has been one of its most frustrating and confusing aspects. The alternation between what is taken as good and the clearly bad has been about the only constant throughout.

What is interesting in almost a comical manner is how “reflation” seems to have taken a life of its own more and more divorced from sense. When exports rose for June 2015, the excitement at that time was understandable from an orthodox perspective because it had appeared to that perspective as if the PBOC and Chinese authorities had been actually doing things that were expected to pay off relatively soon. There was also the pervasive though utterly mistaken view that the global economy was in “transitory” weakness and would break out at any moment.

In December 2016 extrapolating now November 2016 numbers in the “reflation” view attributes it to factors that haven’t happened, aren’t going to happen for some time, and we aren’t even sure we know what it will actually be anyway. As the analyst quoted at the start said, “the expectation of further economic recovery on Trump’s US$500 billion infrastructure spending plan are lifting demand for Chinese products.” That is just nonsense because, again, we don’t know what Trump will do or can even manage to do, and even if he manages to do whatever that is, “it” won’t start until late next year and far more likely get pushed into 2018.

In other words, the economist likely doesn’t really have any idea as to why exports were relatively better this month, so it was just lumped into “reflation” euphoria because, why not. Useful insight is almost impossible for orthodox commentary under these conditions. This has been the state of analysis for not just China but almost all economic statistics since 2014, and in a lesser way going back to 2011. It is one measure of confirmation that this deficient economy continues.

Stay In Touch