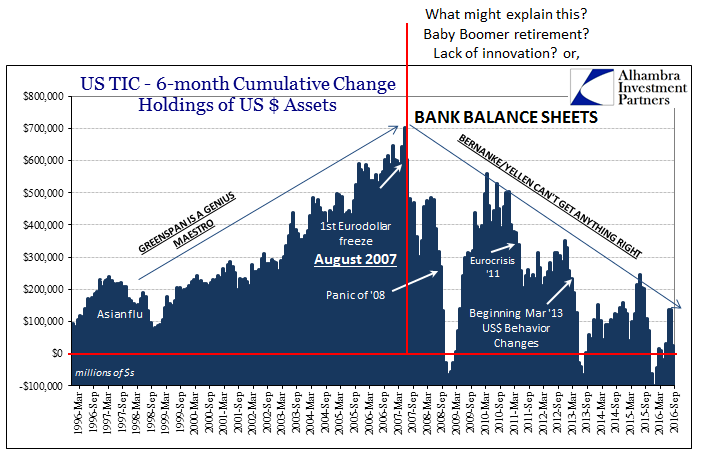

One of the biggest challenges facing central banks in this increasingly post-myth environment is that they have to deal with the consequences of those past myths. Not all that long ago, it was widely believed that a central bank just did what it wanted to do, and that was the end of all discussion. If the Federal Reserve wanted to target a specific money rate, it did and the money rate dutifully obeyed.

At the height of monetary policy legend in the late 1990’s, this precision and ability was extrapolated into the real economy. If the “maestro” wanted the federal funds rate at X, the federal funds rate would not only be at X it would also be the best possible X which created the so-called Great “Moderation.” So powerful was monetary policy that it was thought able to accomplish so much by actually doing what was really so very little.

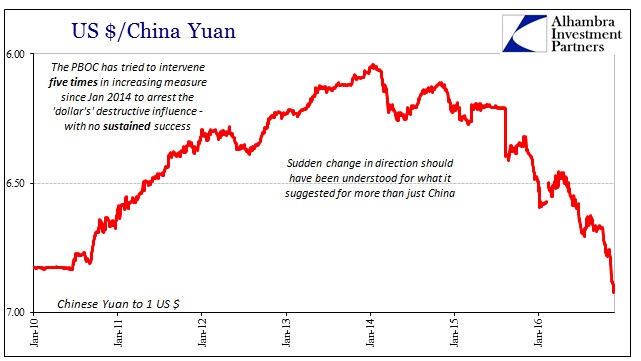

The events starting in August 2007 brought about a fly in the ointment, one that over the past almost ten years has been revealed to be wholesale flaws rather than the minor, temporary irritation of a bug. The “rising dollar” finally thrust these distinctions into the spotlight, for it was very easy to see, at long last, the great contradiction between what QE was supposed to have been and what was clear, global illiquidity traced to “dollars.” The basic idea of QE as it was sold to the public, however, was as if the “maestro” was still at work.

That wasn’t the start of the Fed’s trouble, however, as long before then questions had arisen about defining these terms. As I have written for years, if there had to be a second QE at such an early stage in 2010 there was everything wrong with not just the first but what QE is at least as it relates to the real economy in far simpler terms than the mess brought out by closer examination of wholesale money and banking. Even Janet Yellen in one of her first major policy speeches in July 2014 recognized these “doubts”, suggesting that even the Fed’s policy would in the future be less money, or at least bank reserves, instead being shouldered more and more by the supervisory role:

In my remarks, I will argue that monetary policy faces significant limitations as a tool to promote financial stability: Its effects on financial vulnerabilities, such as excessive leverage and maturity transformation, are not well understood and are less direct than a regulatory or supervisory approach; in addition, efforts to promote financial stability through adjustments in interest rates would increase the volatility of inflation and employment. As a result, I believe a macroprudential approach to supervision and regulation needs to play the primary role.

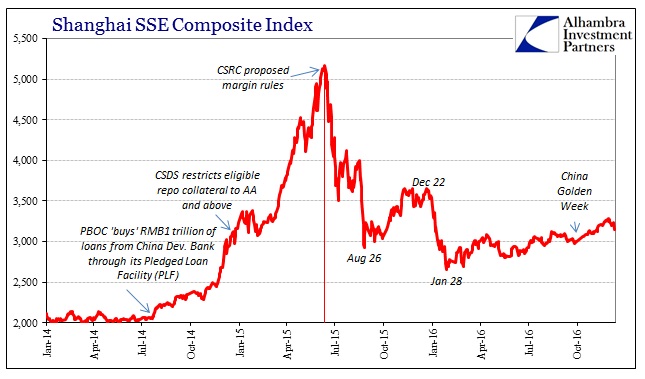

This view is not one exclusively of the US central bank. It has become, or has been to some degree for some time, a central element. In many places it has yet to be fully tested, but in China macroprudential policy has been applied in what looks to be the PBOC’s attempt to straddle both sides of Chinese reality. In many ways, their situation must feel to them something like a paradox, as monetary policy attempts to simultaneously “stimulate” a dangerously flagging economy while at the same time keep its bubbles from spiraling out of control (in either direction).

It is China where myth and reality have most clashed; whenever I get to speaking about the struggles of the PBOC in these microscales inevitably I am met with blank stares of confusion, or the common refrain of, “what do you mean they can’t they just do what they want to do?” The myth of central banking has meant money as an uninteresting monolith, easily molded because of its simplicity to the whims of policy programs. The truth, as ever, is far more complicated. And it was always more complicated, it’s just that hardly anyone noticed because when the global monetary system was building before August 2007 it absorbed almost all policy errors and microscale impediments.

The year 2013 was a turning point for the Chinese. Prior to that year, economic policy on that side of the Pacific was about what you found on this side; “stimulus” in both fiscal and monetary channels, with the latter increasing. The scale of all that intervention in China produced massive financial imbalances that the orthodox textbook said was the price of having to intervene and create recovery. The textbook left blank, however, what do in the event of a scenario where “stimulus” creates those imbalances but not the recovery to absorb them. It was just assumed that “stimulus” always worked in the economic sense.

The global slowdown that developed “unexpectedly” starting in 2011 but manifesting broadly in 2012 pushed Chinese officials to make a choice; continue with “stimulus” and bubbles, thus facing the prospects of becoming Japan 1989, or reform in order to bring reality into the equation where imbalances were the opposite of where everything was supposed to be.

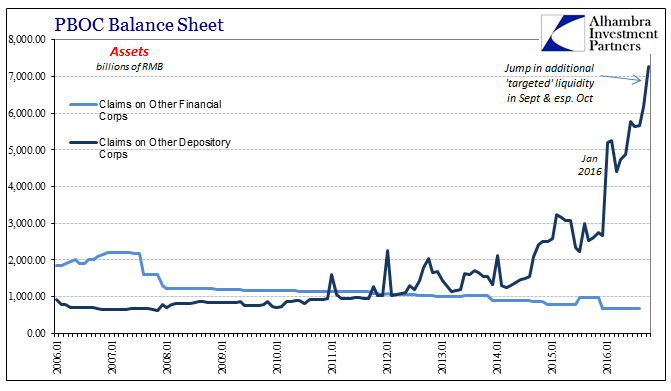

Having chosen reform in late 2013, the Chinese were confronted almost immediately with its consequences. The economy, despite mainstream insistence that it was stabilizing and preparing once again to grow as it had pre-crisis, only got worse. Rather than undertake broad-based “stimulus”, the PBOC began a “targeted” approach. The central bank had developed several new tools with which to offer more than just blanket “liquidity” in RMB. Among them was the Standing Lending Facility (SLF) as well as the Pledged Supplementary Lending (PSL) facility.

The difference in these programs as well as the overall approach was that the PBOC would no longer be so universal in its liquidity or “stimulus” efforts. Rather than flooding the Chinese system with RMB by lowering the reserve requirement or drastically cutting rates, use of these programs would mean channeling RMB liquidity into the large state-owned banks and thereby, it was believed/hoped, stimulating only loans and lending rather than loans, lending, speculation, and everything under the sun. They wanted only the economy to be affected by monetary injections rather than economy plus bubbles that remain a serious risk.

This is one element of macroprudential outlook married directly to central bank liquidity. It’s something that the ECB also tried starting in 2014, with its “Targeted” LTRO’s. In both cases, Europe as China, they quickly devolved back into more broad and traditional (for the 2010’s) liquidity schemes; in Europe, targeted was left behind by the eventual embrace of QE, while in China the PBOC eventually started cutting rates and reserve requirements.

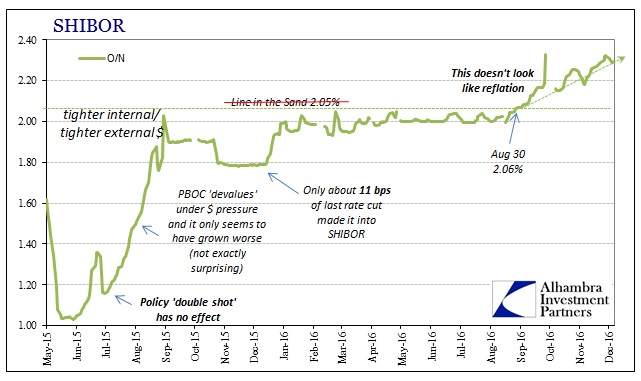

It was at least more faithful in the Chinese approach, as monetary “stimulus” throughout 2015 was limited, especially in direct RMB injections. You can see it in the confusion, almost pleading, of the media and economists (redundant) time and again for the PBOC to intervene as the orthodox textbook says. The central bank gave only limited cuts, sticking with its targeted, macroprudential scheme even to now.

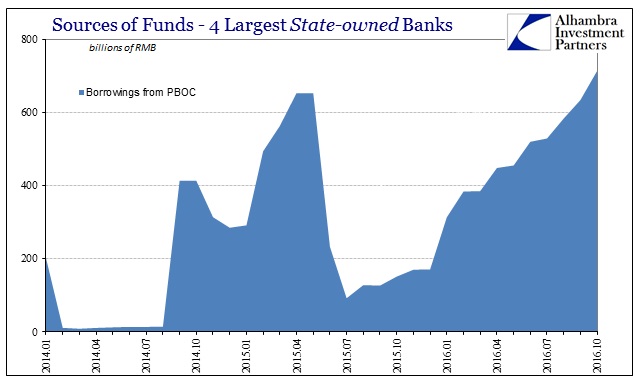

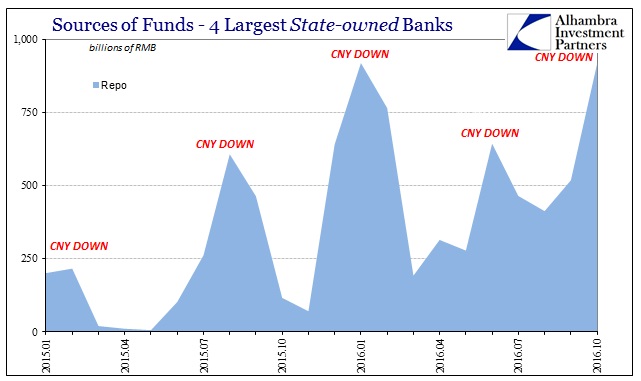

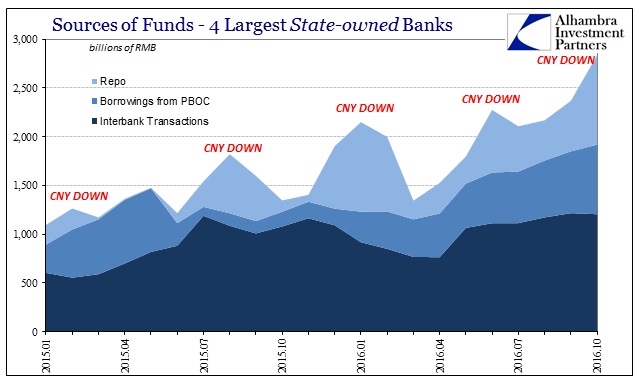

From the balance sheets and call reports of the four largest state-owned banks, this approach is clearly visible. Though it remains unclear as to why in July 2015 the PBOC suddenly reversed course in funding these banks (I suspect it had to do with the first “ticking clock” of CNY being pegged at 6.19 for three months already to that point), what is clear is that they attempted to at least shift the funding mix. The borrowings from the PBOC in the SLF and PSL (as well as the MLF) are not overnight or short-term, whereas something like repo funds provided would be.

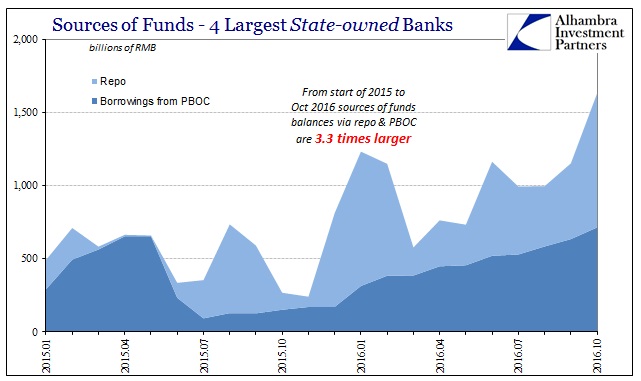

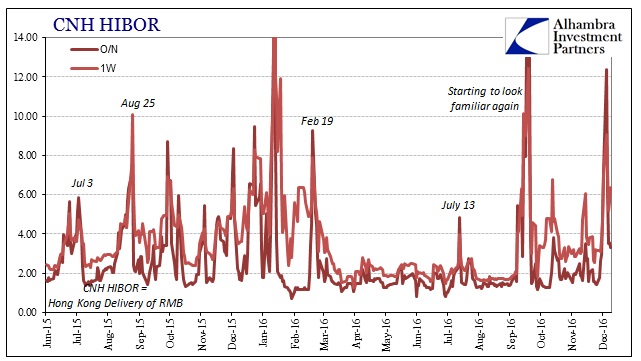

Thus, whenever you find the CNY rate falling sharply as it has since January 2014 you also find the big 4 SOB’s spiking in their repo sources (which includes repo funds provided by the PBOC), including August 2015 and January 2016. Putting these two funding channels together, the “targeted” liquidity approach is clearly visible. As of October, total funds obtained from these two categories have more than tripled since the start of 2015.

Adding in total interbank transactions, we find that the overall wholesale and central bank policy funding has likewise tripled in the past year and ten months through this top-heavy channel.

The difference in 2016 is that funding in RMB for these banks has been far more stable, especially in PBOC borrowing that is more a straight line than the protruding, irregular hump of 2015.That would account for some of why RMB can be increasing often in large amounts but broad money market indications like SHIBOR and HIBOR are displaying the opposite conditions. The big banks have RMB that the “speculators” do not because outside of a clear, immediate emergency the big banks have been classified as the only economically-useful window for monetary policy.

This does not mean that these “targeted” channels are completely efficient and productive, however. It may be that, for example, the big banks are lending short and medium term funds to Chinese insurance companies who have been, apparently, desperate this year to buy Chinese stocks:

A string of high-profile share purchases by such insurers had helped push the Shanghai market to a recent 10-month high. By the end of September, insurance funds held stakes in nearly a quarter of all listed Chinese companies, with total holdings of 1.04 trillion yuan ($150.56 billion), up more than 80% from the same point two years ago.

It may be that “targeted” monetary RMB policy after August 2016 became even more “targeted” because of these kinds of complexities. Notice the huge disparity between the amount of wholesale and policy funding at the Big 4 in both September and especially October versus what is clearly suggested by SHIBOR and HIBOR as the opposite.

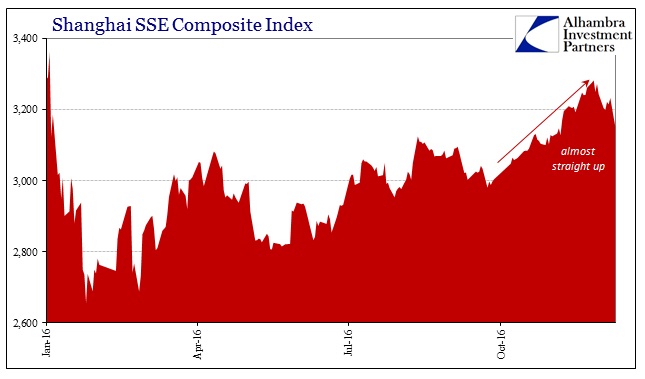

Yet, the Shanghai SSE stock index went on a run throughout October and November – as if “targeted” liquidity was being used for speculative purposes. Chinese authorities apparently agreed with that assessment, with insurance regulators Friday expressly forbidding Evergrande Life, the insurance arm of China Evergrande Group, from buying any more stocks. Several other insurers, taking note, issued statements negative for stocks, including Foresea Life Insurance, a unit of Baoneng, declining to further boost its stake in Gree Electric Appliances.

Chinese stocks opened sharply lower today, though with comments by Donald Trump on China’s one-China policy adding to the nervousness, with the Shanghai SSE index falling 2.5% for its largest single-day decline since June.

In the narrow sense of RMB, this latest event highlights the complications of liquidity policy. In China, it has been the case where “stimulus” is meant to be limited in its reach first by targeting the avenues it can take from the PBOC out into the world, and then by cracking down where it shows up anyway in “unhelpful” fashion. You can make the argument, as I would, that what just happened is similar if much smaller than what happened when China stocks crashed last year under the macroprudential policy of more stringent margin rules.

Is it really different if “liquidity” is targeted rather than flooded? Is the fact that the PBOC feels the need to be targeted in its approach say anything significant about more than just China? I think the answers quite obvious in the affirmative, as something to keep in mind lost in the latest round (its fourth: 2007, 2010, 2013, now late 2016) of “reflation.”

Under these conditions (“dollar” and its global economy) there really is no getting away from the intricacies and details of how these monetary things all fit together and move around. Realizing all this leads to, if not requires, a vastly different perspective of monetary policy and central banking. It used to sound so simple: add liquidity, speed up economy; drain liquidity, slow economy. But again, it never was. What we see here and what we find in review of global monetary policies the past few decades is that central banks are and were reactive institutions trying best to handle global money in whichever direction it was and is going. There were just more accolades and reverence on the way up; leaving only strain, pressure, and error to mark the way down (so far).

Stay In Touch